Early on the first day of New York’s IndieCade East, game developer Frank DeMarco carefully taped a bottle cap he’d found in the trash onto the keyboard of a Strawberry Cubes arcade cabinet.

“It’s so players can’t press the escape button,” he explained, “and escape from the game.”

IndieCade East, a festival of independent games held April 29–May 1 at the Museum of the Moving Image, was just starting to fill with game developers and fans. Here, video games with low budgets, or even generous ones unfettered from behemoth publishers, teased at gaming’s most well-trod tropes: first-person shooters, dungeon-crawlers, military strategy. An especially tense game of Push Me Pull You, in which you and a partner each control one half of a writhing CatDog-like human, attracted a bewitched crowd. The controller for the indie game Butt Sniffin Pugs was, in fact, the rear end of a stuffed pug doll.

Video game esoterica at IndieCade is championed as the truest expression of the form. Yet, for the first hours of the showcase, Strawberry Cubes remained relatively untouched.

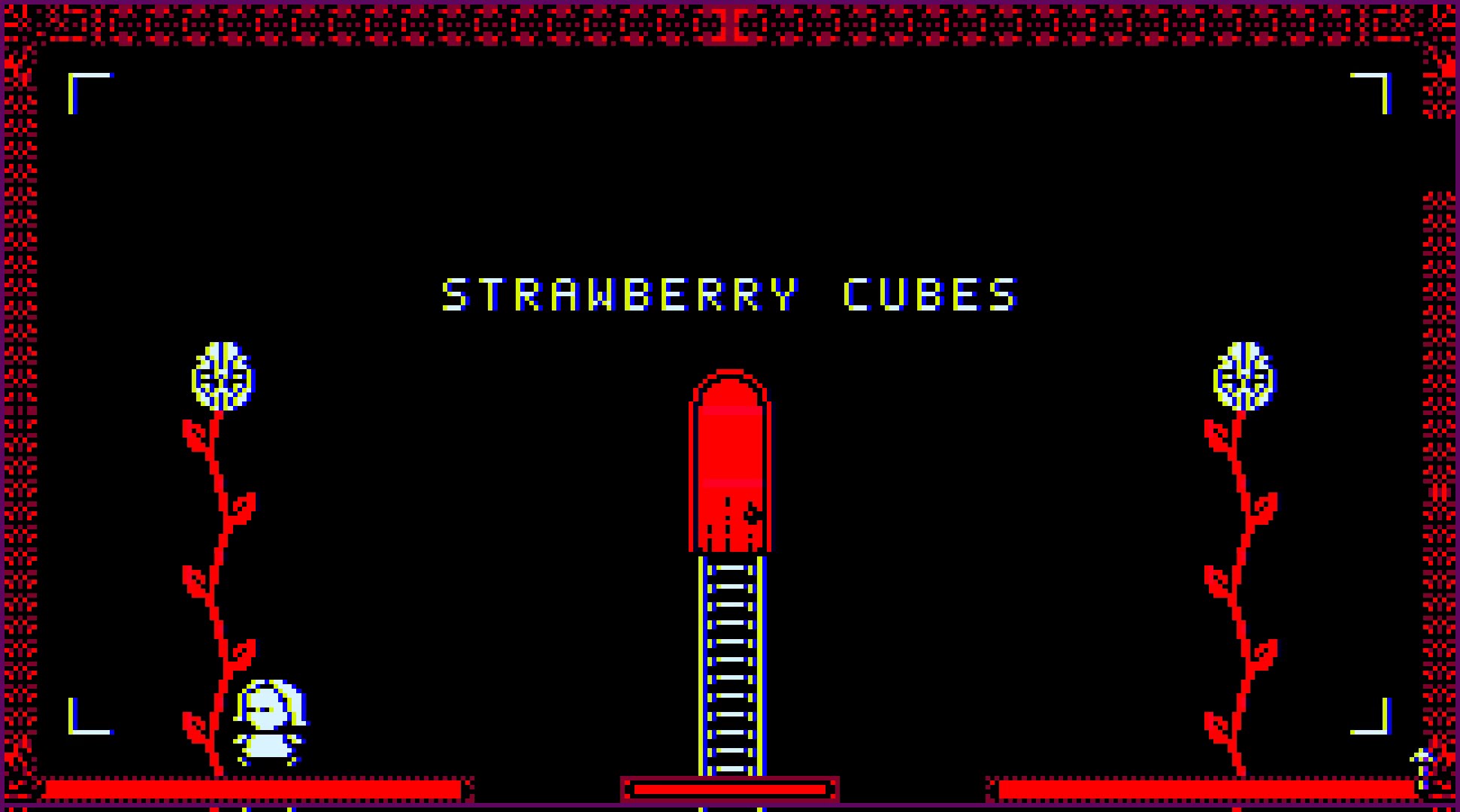

On the screen, a squat girl stood in front of a red door. The ground resembled a spinal cord and, nearby, a flower stalk bloomed. A basic arrangement of single-color pixels comprised the low-res graphics. Opening the door, the girl character found herself in a room with many doors. Whales floated through the sky. She moved left until a new room appeared and, in it, nonsense letters materialized above her head alongside white bricks. Through another door, she entered a blank room from the top of the screen and proceeded to fall for a period of time.

“There’s some logic to this game,” DeMarco, who was tasked with setting up the game, said without confidence. He pressed the F key, spawning an infinite number of leaping frogs.

Strawberry Cubes is a game without a goal. Its rulebook simply reads, “Try pressing other keys.” Players navigate its chaotic, meaningless pixel world with the simple intention of figuring out what is going on and what will happen next—questions that are, by design, unanswerable.

That design is not a sardonic joke. It is, in fact, part of a larger a trend in video game development that is changing our culture of digital play: procedural generation.

In most video games, developers manually place elements, like walls and rocks, on levels to create puzzles and challenges for players to solve. Enemies are likewise designed with a considered attack strategy in mind, forcing the players to hone a game-specific skill set and earning them a sense of mastery.

Nearly every blockbuster game from Mario to Final Fantasy guides players through levels of increasing difficulty to the end of the plot, where they reap the rewards of a job well done.

“This is the fun of the game—trying to figure out what’s going on.”

Games hinging on procedurally generated elements run in the opposite direction: algorithms—pieces of code—generate content, spanning from world terrain to enemy placement. Developers spend their energies crafting these content-generating algorithms rather than fashioning the content themselves. The impression of randomness is powerful since no two levels, enemies, or play-throughs will ever be the same. Difficulty is rarely a factor. Generally, the highest ambition of these games is exploration.

To many gamers, games that take advantage of procedural generation are a refreshing break from the culture’s traditional obsession with competition and finesse.

Although the term is just now gaining widespread traction, the technique of procedural generation has been around for over 35 years. 1980s dungeon-crawler Rogue boasted maps with randomly generated layouts and object placement. (The role-playing game Diablo in 1996 did the same.) Most conspicuous among games with procedurally generated content is the open-world exploration game Minecraft, which has sold over 22 million copies. Minecraft contains no content hand-placed by developers: players construct whatever they want out of 3D cubes in the procedurally generated terrain. As players explore, randomly placed trees and mountains dot the landscape, challenging their structural ambitions.

Google searches for “procedural generation” skyrocketed in conjunction with the announcement of No Man’s Sky, the highly anticipated sci-fi indie game slated for release next month. Last year, The New Yorker published a 6,000-word feature on the game, in which players explore the cosmos and its 18,466,744,073,709,551,616 distinct procedurally generated planets. On one of them, the player descends through a green misty atmosphere before landing on a windy sandscape where she can explore caves or traverse twisted desert rocks. On another, snakelike creatures writhe through the sky. The ground is a jungle, where cooing and purring creatures hide in the brush. “By comparison,” The New Yorker’s Raffi Khatchadourian wrote, “the game space of Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas appears to be about fourteen square miles.”

Nobody is responsible for any planets’ composition—like Strawberry Cubes, No Man’s Sky is composed of a logical assemblage of random elements. For that reason, it is unmasterable and endlessly playable.

Without a linear story, video games with procedurally generated elements can frustrate gamers who approach them with a rigid conception of gaming: encounter a challenge, defeat it; rinse, repeat until the final victory. As the organized and sponsored multiplayer video game matches that comprise the eSports industry reach a projected $500 million in global revenue for 2016, the competitive aspects of gaming have never been more pronounced. Mastery is an appealing impetus to play games, even according to researchers who study the psychological motivations behind gaming. In stark contrast to real life, success and failure in video games is obvious, demarcated by rewards and punishments. A decade of study has shown that traditional video games activate the brain’s pleasure circuits with great felicity.

However, now that mainstream publications have realized that, indeed, video games can be art too, public perceptions of what constitutes “video games” have shifted. Digital projects that do not at all contain tenets of gaming set forth by classics like Mario or Street Fighter are becoming less incongruous with the form. Procedural generation has always been around, but its recent spurt in popularity, perhaps, is due to widespread interest in events like IndieCade, which are forthcoming in their mission to redefine the range of gaming experiences.

Steve Schultz, founder of the educational game company Starfall, observed DeMarco meander through Strawberry Cubes. By that point, DeMarco had settled on a strategy: move as far right as he could. He couldn’t figure out how to plant seeds for the flower stalks, or whether that was an essential game mechanic at all.

“I don’t think this would work with my elementary kids,” Schultz mused. Starfall’s flash games incentivize learning how to read, earning them rave reviews from parents on the iOS app store. “The concept behind this wouldn’t work. They want to achieve something, solve an equation or a problem, like getting into a house with a key.”

When I posed Schultz’s criticism to Loren Schmidt, the Strawberry Cubes developer, Schmidt was bemused: “That kind of thinking is so engrained.”

“The game has collectables, but they are entirely unnecessary. There are puzzles involved in getting the collectables, but you can always break the game and not solve the puzzles. It’s very consciously not about a sense of achievement or mastery,” Schmidt added.

As the first day of IndieCade East came to a close, the arcade floor grew crowded. Game developers and journalists took turns navigating Strawberry Cubes’ algorithmic disorder with varying degrees of patience. Mo Mozuch, a 32-year-old editor at iDigitalTimes, attempted to climb up a wall but instead fell through the spinal cord floor. “This is the fun of the game—trying to figure out what’s going on,” he said.

Loren Schmidt charged a flexible fee for the game with a $1 minimum. Schmidt says that Strawberry Cubes has been downloaded 10,000 times since July, 2015. For a game described in a Kotaku headline as “A creepy game where you have no idea what the hell is going on,” Schmidt’s procedurally generated rabbit hole did pretty well.

As the success of No Man’s Sky is assured, considering its wide-eyed media coverage over the last few years, games capitalizing on procedural generation will, in all likelihood, flood the market. Perhaps exploration will trump mastery as a lure to game, expanding notions of the “gamer” to include casual, curious play.

Eventually Mozuch began to tire of Strawberry Cubes, apparently frustrated by its inscrutability. “The rooms are stitched together, but I don’t know what would constitute a play-through,” he said. He paused and, shrugging, began playing again, pressing through into new rooms.

Cecilia D’Anastasio is a Brooklyn-based journalist writing on escapism, justice, and women.

0 Comments