When the media became aware of the protest centered at Wall Street during the fall of 2011, a predictable line of questioning immediately appeared—whatever in the world are they protesting? Of course, everyone who came near Zuccotti Park knew exactly why the protesters were there. Given the scale of the economic crisis, Main Street’s bailout of Wall Street, and ongoing oligarchy, the “only surprise [was that it took] so long for the citizenry to take to these particular streets.” The graphic polarization of their chant—“We Are the 99%”—made it all the more clear.

In the years since the destruction of the occupations, this critique of inequality has only broadened and deepened in the U.S. Occupy should claim credit for getting it on the map, while political iterations old and new have been keeping it there. Today, the fight against inequality is taking greater institutional shape, and seemingly exerting more leverage, in places inspired by Occupy but moving beyond its initial tactics.

Studying Occupy Wall Street in New York from its inception and through 2012, my colleagues and I traced the “enduring impact” of OWS through various measures, including the ongoing movement participation of core participants and the proliferation of “Occupy after Occupy” efforts—what journalist Nathan Schneider described as a “productively subdivided movement of movements.”

And workplace by workplace, franchise by franchise, ordinance by ordinance, council member by council member, co-op by co-op, the struggle continues.

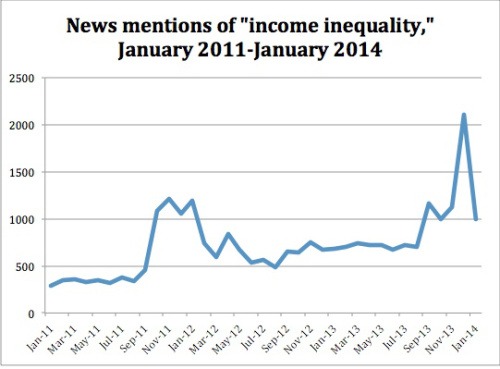

Joining most observers, we noted that Occupy’s impact was most easily traced in the extent to which it had shifted the discourse in the United States. “Income inequality” was suddenly in the headlines. We included a graph that showed how frequently the phrase was invoked by the media pre-, during, and post-Occupy. We found that news mentions of “income inequality” rose dramatically with the outset of Occupy, and in the aftermath remained substantially higher through the end of 2012 (up about a third from pre-Occupy levels).

I ran the numbers again this week, and I have to admit I was surprised by the results.

As we’d seen before, in the year after Occupy’s peak, the numbers stayed higher: 30-50 percent of the pre-Occupy discussion. But beginning in the fall of 2013, the numbers reached Occupy levels again, and this time rising to over 2,000 mentions of the phrase “income inequality” in December 2013—over 50 percent more than Occupy’s peak.

Of course, I shouldn’t have been surprised to see this rise. The occupations have gone away, but neither the crisis nor the resistance has disappeared. Low-wage and precarious workers are at the forefront of the fights today, and they are keeping inequality in the spotlight. This past fall and winter we’ve seen fast food strikes and the “Fight for $15”; other minimum wage fights around the country; Walmart workers demanding $25,000 a year; university adjuncts organizing and striking. Workers, unionists and Occupy veterans, through traditional labor and “alt-labor” organizations are elevating the fight and pushing for concrete change. Tailing these developments, figures from President Obama and Gap Inc. are now simultaneously pushing for (highly inadequate) wage increases.

Media attention to inequality reflects recent electoral shifts as well. Mayors who ran left were decisively elected in New York, Seattle, and Boston. (Occupations existed all over the country, but it would be interesting to probe the relationship between those Occupations and new electoral outcomes. Certainly, these three cities were home to sustained and popular occupations in fall 2011.) Labor’s candidates and initiatives did well overall, in the 2013 local election cycle; and in Seattle, Occupy activist and socialist Kshama Sawant was elected to the City Council. While many of the core Occupy activists eschewed electoral politics, we nevertheless see the outlines of their critique emerge in race after race.

As important as Occupy’s inspiration has been as the carrot encouraging these new movements and electoral shifts, the ongoing crisis that working people are experiencing and the desperate straits that unions and other progressives find themselves in provide the stick. Labor, in particular, has been working hard to shift course for many years. Occupy’s eruption was a major shot in the arm, but many of the campaigns we see today have their roots pre-Occupy.

However, the energy and audacity in today’s movements are fueled in part by the experience of Occupy (and the organizers who started the occupations and emerged from them). Direct action and prefigurative practices inform many of the efforts that contribute to today’s groundswell, such as the strikes and walkouts. But unions are also exploring worker cooperatives, community groups and activists are forestalling foreclosures through occupations, and activists are tying collective student debt refusal to the demand for free higher education.

The Occupy activists we spoke with two years ago echoed each other, saying that the movement needs to “take the long view” and remember that change doesn’t happen overnight. I haven’t spoken with enough of those activists today to know their assessment of the fights they see and are participating in today. They are not out there, all day, all week, occupying Wall Street—and it wasn’t enough when they were. The scale of necessary social transformation remains daunting, and questions of both strategy and power loom large.

But all day, and all week, more people are talking about inequality and directly fighting against it. And workplace by workplace, franchise by franchise, ordinance by ordinance, council member by council member, co-op by co-op, the struggle continues.

Penny Lewis is an Assistant Professor at the Murphy Institute for Worker Education and Labor Studies, School of Professional Studies, CUNY. She is also the author of Hardhats, Hippies and Hawks, The Vietnam Antiwar Movement as Myth and Memory. She wrote this for Working-Class Perspectives.

0 Comments