Nominally, it was a fight about whether the speaker should allow the House to vote on legislation to keep the government open. Conservatives wanted to block the legislation as part of a crusade to defund Planned Parenthood. But John Boehner’s decision to resign the speakership was about much more than funding Planned Parenthood. It was, in fact, about the steady unraveling of a coalition that has allowed the Republican Party to hold the White House for 28 of the past 47 years and maintain a seemingly solid base for continuing control of the U.S. House of Representatives. As the coalition unraveled, Boehner simply could not hold on any longer.

Ever since Kevin Phillips published The Emerging Republican Majority 46 years ago, there has been a serious flaw in the contract that holds the party together. Today’s GOP is made up of two groups that are polar opposites among White Americans. The traditional wing of the party is not simply pro-business but represents a large majority of the country’s corporate leadership, financiers, and investors. Some call these the “country club” Republicans, and while they are a small fraction of the voting population, they have enormous resources to influence the voting behavior of those not privileged to hold a country club membership.

At the opposite end of the economic and educational spectrum of White America is a group that was welcomed into the Republican fold by Richard Nixon in 1968 and 1972. Their numbers make the Republicans a formidable national party. The problem is that this latter group has almost nothing in common with the country club wing of the party. Country clubbers don’t care about prayer in the public schools, gun rights, stopping birth control, abortion, and immigration (i.e. restricting their own ability to hire illegal aliens).

On the other hand, the largely poor, rural, church-going whites who have swelled the party’s electoral turnout don’t care about marginal tax rates, capital formation, or government subsidies to large corporations, such as those provided through the Export-Import Bank. If they ever fully understood that their more prosperous party brethren were contemplating deep cuts in Medicare and Medicaid to pay for those policies, they would be in open rebellion.

John Boehner has spent most of his 27 years in the House trying to hold these two groups together. That was not an easy job in the ’90s. It has become more difficult as rural America has become more and more Republican and the lopsided margins rural voters provide at the ballot box have led to a bigger, more unruly Republican delegation in the House. After the Republican landslide in the 2010 off-year election, holding the GOP conference together required not only consummate political skill but more than a little bit of magic. Even John Boehner could not keep the cars of the train coupled together and on the same track.

John Boehner’s is the first scalp they have claimed in seeking to express their discontent. It won’t be the last.

Boehner’s departure will provide observers with some insight into the unique skills he brought to the position. Since his early days in the speakership in 2011, when many of his colleagues thought it would be really nifty for the United States to default on its public debt, Boehner has shown not only extraordinary patience, but an ability to listen to his colleagues, understand their bottom line, and fashion compromises that few politicians could have crafted.

In 2013 he demonstrated remarkable guile by recognizing that he was not dealing with reasonable people and that he could only win in the end by losing in the beginning. He repeatedly warned House Republicans in September of that year of the disaster that would befall them if they blocked legislation that would have averted a government shutdown. But he also recognized that the following year would present even more landmines for his party, and getting his colleagues to behave themselves in an election year might require that he allow them to misbehave in the interim and feel the wrath of public displeasure as a consequence.

It worked. Boehner caved to his right wing and the government was shut down for the first 16 days of October 2013, idling 800,000 federal workers. (The issue this time was defunding the Affordable Care Act.) But on October 16, the renegades had finally begun to see the light. They not only reopened the government, but appropriated money to pay the salaries of furloughed federal workers. And they remained on good behavior for the remainder of the 112th Congress.

House Republicans allowed conferees to work with their Senate counterparts on a full-year omnibus appropriation that was signed by the president in January. In February, the House again surprised its detractors by suspending the debt limit and avoiding another possible default. That September, weeks before the November elections, the House took the responsible route and passed a continuing resolution allowing the government to operate without restriction until regular appropriations could be passed after the election.

Despite the huge public outcry and distaste for the Republican performance at the time of the shutdown, the worst of that period was forgotten by the time voters went to the polls the following November. Under Boehner’s leadership, Republicans not only held their majority, but added to it in 2014.

Unlike his two Republican predecessors in the speakership, John Boehner is a legislator. He has chaired a committee; taken legislation to the floor, and crafted compromises with the Senate that were signed into law by the president. Neither Dennis Hastert nor Newt Gingrich had ever chaired even a subcommittee or managed the debate on a single bill on the House floor. The legislative resume of Boehner’s likely successor, Kevin McCarthy, is equally sparse.

Now we will witness the House without John Boehner. The underlying issues that brought him down have not gone away. The business wing of the Republican Party is openly appalled by not only the antics of many House Republicans but by much of the Republican presidential field. Social conservatives and Tea Party members are convinced that the business wing of the party is not only insincere about its support for the policies the conservatives advocate, but secretly works to undercut those policies. John Boehner’s is the first scalp they have claimed in seeking to express their discontent. It won’t be the last. In the process they have driven off the stage the one man who had the skills to keep the Congressional wing of their party together.

Scott Lilly is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. He worked in the House for 31 years in various capacities, including as staff director of the House Appropriations Committee.

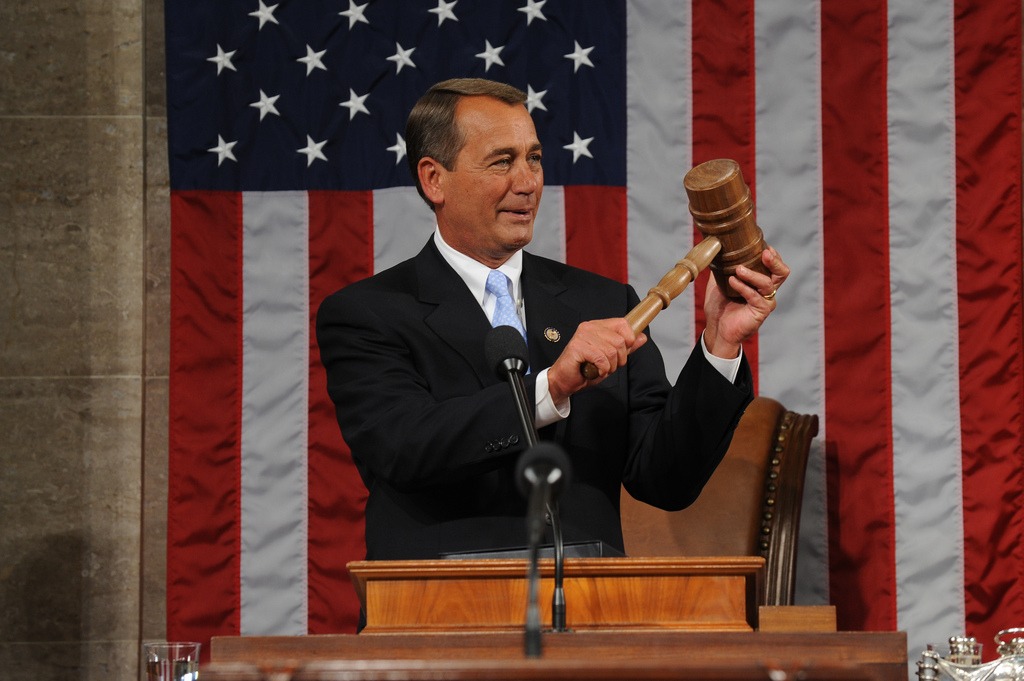

Photo courtesy of Speaker John Boehner.

Correction: This post has been updated. An earlier version of this story noted that Republicans have held the White House for 27 of the past 47 years. It’s 28 years, not 27.

Scott, as usual, you are spot on! Congratulations on an excellent article. Trust all is well with you and yours.

Scott–As you frequently do you expressed my thoughts much better than I could–Bob

Thank you for your analysis, explanation and knowledge of the institutions and it’s players.