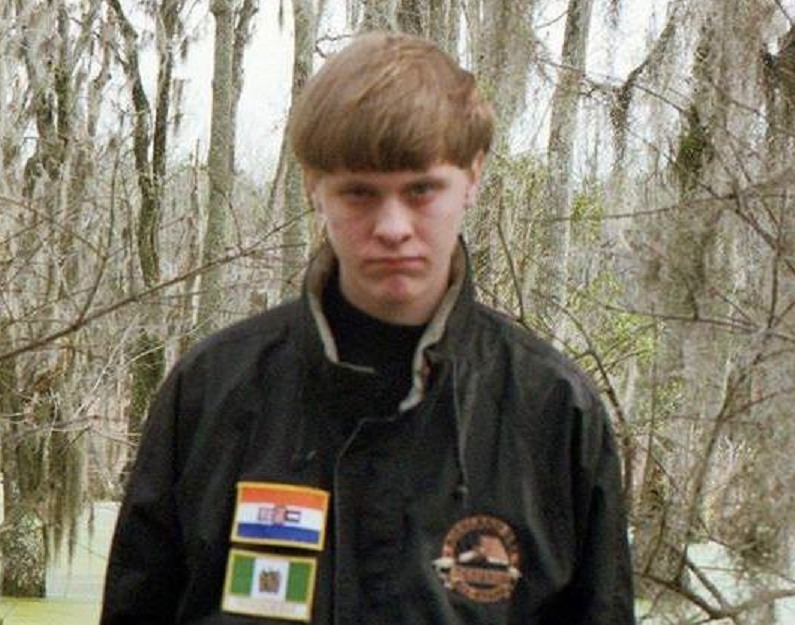

When Dylann Roof pulled a gun at a Bible study in Charleston, South Carolina, his shots rang through history to the roots of the ideology of white supremacy, which justified genocide of indigenous peoples and the enslavement of black people from Africa. We deny this at our own risk.

Roof attacked the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, which by the early 1800s was at the center of black resistance to slavery in Charleston, according to African-American history scholar Gerald Horne. Black people, Roof feared, threaten the existence of the white race. Events in the church’s history play a role in Roof’s fear. Inspired by a slave rebellion that began in 1791 in what is now Haiti, Emanuel parishioner Denmark Vesey of Charleston began organizing an insurrection against slavery, using the Charleston AME church as a base.

We need to revoke that grant of privilege by working to correct the injustice that still stains our nation with the spilling of blood.

Roof might have been unaware of the specific history of “Mother Emmanuel,” but he had immersed himself in a narrative that is deeply rooted in our nation’s history, a narrative that takes into account the history of Charleston’s historic congregation.

Roof told a participant in the Bible study, “I have to do it. You rape our women and you’re taking over our country. And you have to go.” Horne and other social scientists believe Roof inherited the fear of murderous blacks raping white women from a common historic narrative of white supremacy.

Horne says that after the bloody slave revolt, American newspapers were full of stories salaciously describing “marauding blacks with sugar cane machetes hacking the white slave-owners to death.” Regardless of their veracity, these stories informed a historic narrative that was seized upon by the founders and early members of the Ku Klux Klan.

After the Civil War, the Ku Klux Klan “was largely halted following federal legislation targeting Klan-perpetrated violence in the early 1870s,” said Klansville, U.S.A. author David Cunningham in a PBS documentary. In 1905, Thomas Dixon, Jr., wrote The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, later turned into the silent film The Birth of a Nation in 1915. The white supremacist frame of black men pillaging, raping, and murdering was returning to the mainstream.

Dylann Roof looked beyond our native anti-black texts. His website was The Last Rhodesian. Roof allied himself with the cause of Rhodesia because, according to the racist right, the failed struggle in the 1960s to preserve African white nationalist societies, including South Africa, was a warning about the communist conspiracy to use black people to pave the way for totalitarian tyranny. This thesis was purveyed by the John Birch Society, whose historic and current conspiracy theories are today utilized by Glenn Beck. A decade before he was appointed to the Supreme Court, Justice Clarence Thomas joined the conspiracy theorists when he became affiliated with the Lincoln Institute, a right-wing think tank that embraced apartheid in South Africa as a bulwark against communism.

As the world is wired today, these theories are a click away. Jennifer Earl, the co-author of Digitally Enabled Social Change: Activism in the Internet Age, is one of several sociologists to have shown that the internet can mobilize people into movement participation. Right-wing groups from the militia to the neo-Nazi movements were early adopters of online technology, even before the internet created a world wide web of unedited communications that brought racist and anti-Semitic (and now anti-Islamic) rhetoric into our homes.

Roger Griffin studied terrorism for the British government. His Terrorist’s Creed: Fanatical Violence and the Human Need for Meaning, describes the phenomenon of “heroic doubling,” which can turn a “normal” individual into someone who carries out acts of fanatical violence as a media-carried clarion call to arms to defend an idealized pure community under threat from a demonized “Other.”

Roof was influenced by the Council of Conservative Citizens. The CofCC’s racist rhetoric provides the most extreme versions of the demonization of blacks and white liberals, while a more muted—sometimes coded—version of white supremacy is routinely broadcast on cable news and AM radio talk shows. The first black president continues to provide a lightning rod for racist rhetoric.

White nationalism infuses our political ideology as a nation—from our major political parties to the armed extreme right. We need to confront the color line that bestows on white people unfair advantages. We need to revoke that grant of privilege by working to correct the injustice that still stains our nation with the spilling of blood. As Dr. King warned us, either we build community or we will face chaos.

Chip Berlet is the co-author of Right-Wing Populism in America: Too Close for Comfort.

See also: “Mapping Organized Hate“

0 Comments