Because of rulings from the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals and the United States Supreme Court, the Republican governor and Legislature of Texas have succeeded in excluding as many as 844,000 eligible voters from this November’s national, state and local elections. Many of those voters are African-American or Hispanic. Many would have voted for Democratic candidates.

Here’s how the Campaign Legal Center—which was involved in the trial in federal court in Corpus Christi, Texas, where a district judge ruled the Texas voter ID law unconstitutional—began its press release.

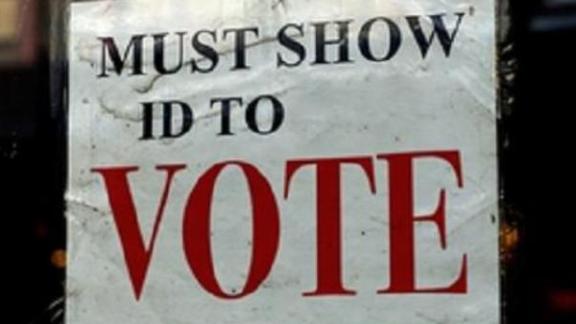

This morning, in Veasey v. Perry, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to stop a Texas voter-ID (SB 14) law from being used in the upcoming election, despite the fact that one week earlier a U.S. District Court ruled the law unconstitutionally racially discriminatory and a poll tax. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit had subsequently stayed that ruling, leaving SB 14 in effect due to concerns that striking down the law now would disturb the upcoming election.

Hardly a surprise. Contempt for the rights of minority voters is the signature mark of the John Roberts Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court’s decision to allow a Texas voter-ID law to go into effect is a yet another outrage in which the Republican majority of the court again reveals itself as a functionary of a party that cannot remain in office without interfering with the voting rights of minorities.

“Our country has changed,” Roberts wrote in the Shelby County v. Holder decision that stripped the Justice Department and federal courts of statutory authority to vet changes in voting laws in states with histories of racial discrimination at the polling place.

The Court’s Republican majority’s willful ignorance of the harsh facts of daily life for racial and ethnic majorities in this country is breathtaking.

Consider the East Texas Protestant minister quoted in the decision in which Federal District Judge Nelva Gonzales Ramos found the Texas voter-ID law unconstitutional.

“They had no civil rights in towns or cities in the State of Texas because of the brutal, violent intimidation and terrorism that still exists in the state of Texas; not as overt as it was yesterday. But East Texas is Mississippi 40 years ago.”

Note that the Rev. Peter Johnson said “is” Mississippi, not “was.”

Judge Ramos followed Rev. Johnson’s quote with an account of the testimony of Texas Senator Rodney Ellis. The Democrat from Houston described a hate-crime in Jasper, Texas, in 1990, when James Byrd, an African-American man, was tied to the back of a pickup truck by white thugs and dragged to death along a rural road.

The judge observed that 20 years after the murder, when the Jasper City Council appointed a “highly-qualified” African-American police chief, the two black council members who pushed for the appointment were “removed from their district council seats through a ‘strange quirk in the law’ that allowed an at-large recall election.”

Judge Ramos couldn’t tell the whole story in her opinion, but like much regarding race relations in Texas, particularly outside the state’s major metropolitan areas, the recall election and subsequent firing of the black police chief was worse than it appears.

As reported in the Washington Spectator’s February 2013 issue, Rodney Pearson was an East Texas highway patrolman when he was hired by the majority-black council in a city that then was 48.5 percent white and 44.4 percent African American.

Pearson, as we reported, was also the highway patrolman who in 1990 had answered a dispatcher’s call and drove to the scene to find James Byrd’s remains scattered along a road near an African-American church in Jasper.

Pearson’s dismissal by the white council majority that ran things after the recall election was so egregious that the city settled a lawsuit with him for $831,000.

Again, like many matters regarding race in Texas, it was worse that it looks.

From our reporting on Jasper:

While preparing the case, Pearson’s attorneys claimed the mayor had used the local radio station he owns to release select material from the police chief’s personnel file, “to portray him as a thief and a criminal, in an attempt to stoke racial animosity in the community.”

The details of the recall drive are spelled out in a 26-page opinion handed down by a federal Magistrate Judge Zack Hawthorn, including a reference to a social media posting circulated by an organizer of the recall, which incorporated a Trojan condom ad with photos of black council members, the police chief, President Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama.

The last phrase, by my lights, is worth repeating: one organizer of the recall election used social media to circulate a political flyer, which incorporated a Trojan condom ad with photos of black council members, the police chief, President Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama.

The focus of our Jasper reporting was on the current white-majority city council’s attempt to annex a large white neighborhood on the edge of the city—to ensure that African Americans will not become a majority in Jasper, Texas.

My belabored point: many regions of the state of Texas are rank with racism.

Or as the preacher testified in court: “East Texas is Mississippi 40 years ago.”

Perhaps that’s why some passages in the introduction to Judge Ramos’ opinion read like a cri de coeur. And that’s also why the Supreme Court’s decision to allow the state’s voter-ID law to go into effect is a yet another outrage in which the Republican majority of the court again reveals itself as a functionary of a party that cannot remain in office without interfering with the voting rights of racial and ethnic minorities.

Judge Ramos presided over a trial that lasted for more than a month, allowing the state and the plaintiffs challenging the voter ID Law to fully make their cases.

Her opinion obviously extends far beyond the anecdotal accounts of racism that I have cited. Set aside an hour or two to read it and you will readily conclude that the Fifth Circuit Court (which sits in New Orleans and is dominated by Bush I and Bush II ideological appointees) engaged in a predictable act of partisan judicial activism when it stayed a lower court opinion that was based on an exhaustive examination of the record.

The Fifth Circuit ruled (and the Supreme Court agreed) that to implement a change in election law less than a month before the election would be disruptive.

The disruption?

To direct election officials not to require voters to show a state-sanctioned ID in order to cast their vote. So the Texas Legislature, which Judge Ramos found has a long history of discriminatory voting processes, prevails.

It prevails by keeping from the polls as many as 844,000 voters, according to Republican Lt. Governor David Dewhurst, who lack a driver license to vote. (You can also vote with a concealed-carry handgun license, but not an ID from a state college, because, well, this is Texas.)

The Legislature (and Rick Perry, the named defendant in the suit) prevails despite the fact that, as the judge found, while lacking evidence of voter-impersonation fraud, the Texas Legislature last year declared passing the voter-ID bill an “an emergency”—thus disposing “of the usual order of business, and ensured that—with unnatural speed—it would reach the end of the legislative journey relatively unscathed.”

“It was,” Judge Ramos observes in one understated phrase “procedurally unorthodox.”

The law stands despite Judge Ramos’ finding that “in every reapportionment since 1970, Texas has been found to have violated the VRA [Voting Rights Act] with racially gerrymandered districts.”

“This history describes not only a penchant for discrimination in Texas with respect to voting, but it exhibits a recalcitrance that has persisted over generations despite the repeated interventions of the federal government and its courts on behalf of minority citizens.”

And recall.

The same five ideological, activist, Republican appointees to the Supreme Court last year gutted the section of the Voting Rights Act that since 1965 required states with histories of racism at the polls to submit laws like the Texas voter-ID act to the U.S. Department of Justice or to a three-judge federal panel in Washington, D.C. for preclearance.

To read this opinion, and the response of Republican appellate justices to a district judge whose surname and the state in which she came of age suggests she knows something about the nature of discrimination, is to recognize that the Supreme Court is working in concert with Republican state legislatures enacting Jim Crow laws that keep blacks and Hispanics away from the polls.

Lou Dubose is the editor of The Washington Spectator.

0 Comments