The view from my condo overlooking the Saigon River includes much of Ho Chi Minh City’s glittery downtown, with its many newly built high rises and the famous Thu Thiem bridge. On a weekday it is crowded with cars and motorcycles. Today, however, that torrent of humanity has, but for a few straggling motorcycles and cars, trickled to a trifling brook out my window.

It’s as if the city had emptied itself out, and there’s a new slowness here that borders on desolation.

Vietnam, like many other countries, is fighting a desperate battle against an invisible enemy, and in its effort to contain it, much is sacrificed. Currently there’s an imposed strict social distancing rule (until April 15, and then maybe a few more weeks of curfew, so goes the rumor, all depending on the rate of infection). Citizens are asked to go out only to shop for food and medicine but nothing else. No barber shops, no cinemas, no eating out, no gym, no shopping malls, no private gathering of guests inside one’s home.

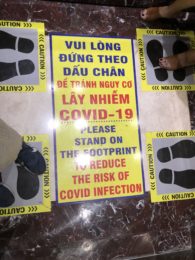

In the morning in my condo complex the loud speaker goes on for about half an hour, with a woman’s voice reminding everyone to practice personal hygiene, that is, to wash our hands, and of course, to wear a face mask when we go out, and to keep a safe distance from one another. She is then followed by Vietnam’s famous corona song, with its message of personal hygiene, a song that had gone viral, for lack of a better word, around the world.

My local cell phone gets a text message or two each day from the health department informing me of the number of new cases. And it reminds me, of course, to follow lockdown rules. And to report myself or others via a hotline if symptoms related to Covid-19 appear.

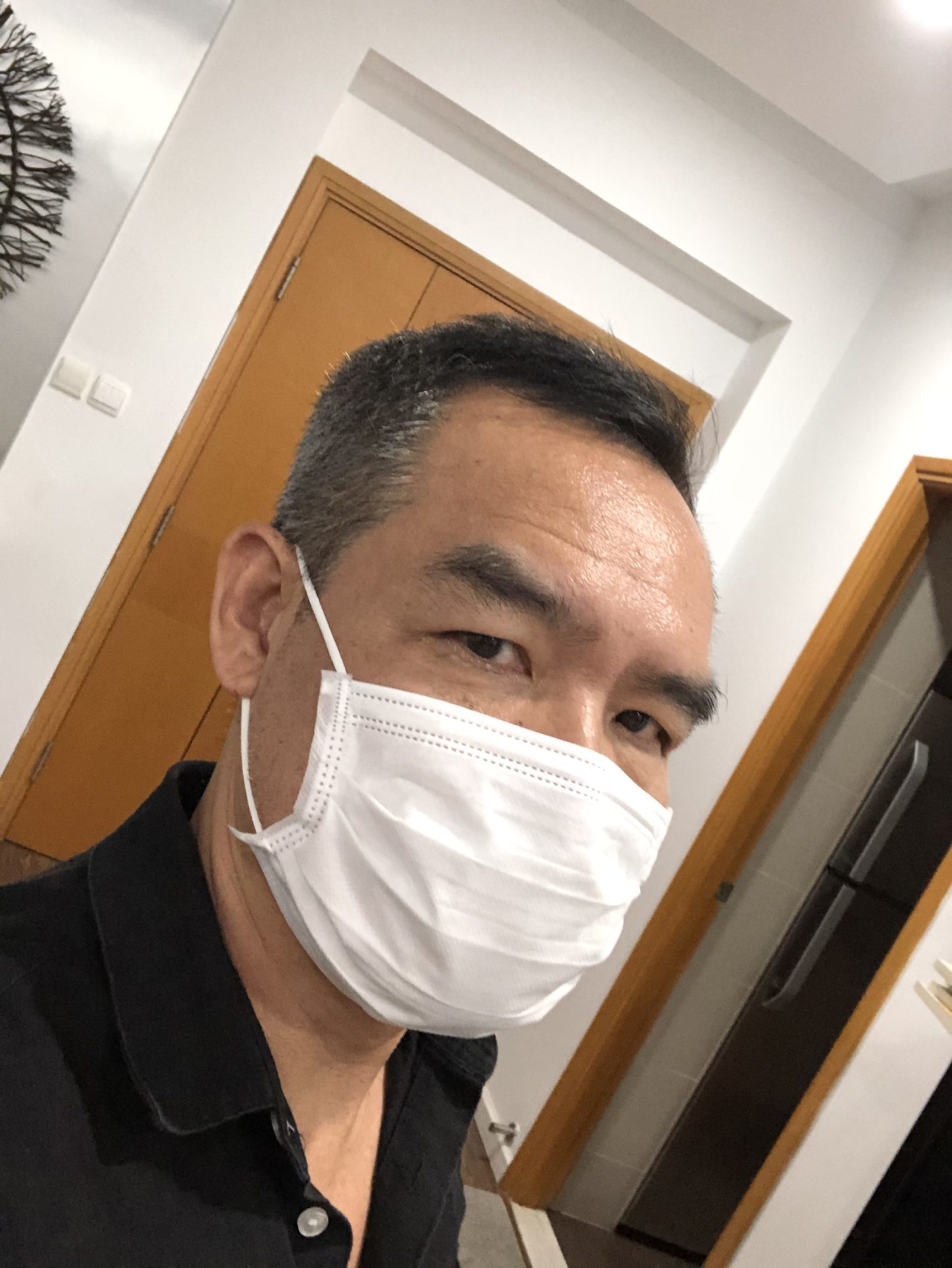

There’s a fine if you don’t wear a face mask here in public. Even if you are wearing one, and it sags below your nose, you may still get a fine. Everyone else will remind you to put your mask on in case you forget. Citizens stay vigilant with each other. Yesterday, I watched a grandmother scolding two young teenagers for not wearing their masks while playing in a courtyard, and the consternation on their faces spoke volumes to the spirit of cooperation that everyone shares.

Visitors and citizens returning from overseas are required to test for Covid-19. According to Vietnam’s tourism advisory, “If you have any contact—such as the sharing of flights, vehicles, or hotels—with others who have tested positive for Covid-19 while in Vietnam, you can expect to be tested for the virus and placed in 14-day quarantine.” For those returning from high-risk areas, they can also expect to be quarantined in “non-medical establishments.” In many cases, these are converted army barracks.

And in instances of high numbers of confirmed infections, entire buildings or blocks are closed off.

Compared to other countries in Southeast Asia, and to China, Vietnam’s northern neighbor, where the pandemic originated, Vietnam’s efforts have been rewarded with impressive results. As of today, April 12, 2020, this country of 96 million people has officially identified only 260 positive cases, with more than 50% having recovered, and with zero deaths.

I repeat, zero deaths.

Among Vietnamese and expats alike, that statistic is top of our conversation: how is it possible? Some speculate that the number of positive cases are much higher. Others speculate that the number of deaths are hidden from the public. Still others argue that unlike China where social media is highly regulated, Vietnam’s Facebook users would quickly share such information as deaths by corona were they to occur. Facebook is the alternative news option here, after all, having captured almost 50% Vietnam’s population in just a few years’ time.

While there are rumors and whispers, practically everyone agrees that the authorities were quick to contain and mitigate the virus. They banned all public gatherings, and then as more cases popped up due to Vietnamese returning from overseas and foreign visitors bringing in the disease, they banned many flights.

Others speculated the it’s due to the BCG vaccine for Tuberculosis that is universally implemented here. Articles of late have suggested that the shot boosts one’s innate immune system.

While the fact that Covid-19 is well-contained is a source of collective pride here, the price for it has been exorbitant: jobs loss, economic slow-down, and the lockdown as it continues is causing havoc. And the toll is growing by the day.

According to the Vietnam Tourism Advisory Council, the Covid-19 epidemic will result in an estimated loss of between $5.9 and $7 billion for Vietnam’s tourism in the next three months alone, and for the rest of year, the picture doesn’t look much better.

Already I know several young Vietnamese college students who fled the city back to their hometowns. School is out, and the jobs they held as waiters and salesmen are all gone. Others are not so lucky. They are stuck in the city with nowhere to go, no jobs to be had, all waiting for better days, and frantically borrowing money to feed themselves. The economic damage may be difficult to estimate at the moment, but just by the look of the shuttered shops, it is considerable and growing.

But such is the price the country is willing pay to fight this invisible enemy. And lately the language used by the government to encourage its citizens to continue the fight harkens back to the propaganda language used during the Vietnam War. “Let’s unite to battle corona…” while doctors and nurses are “soldiers in white…”

The end of this April marks the 45th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War. But Vietnam is too busy to celebrate. And in this new war, clearly it aims to win, again.

Andrew Lam is the author of the memoir Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora, the book of essays, East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres, and a collection of short stories, Birds of Paradise Lost. He’s working on another book of short stories and a novel.

0 Comments