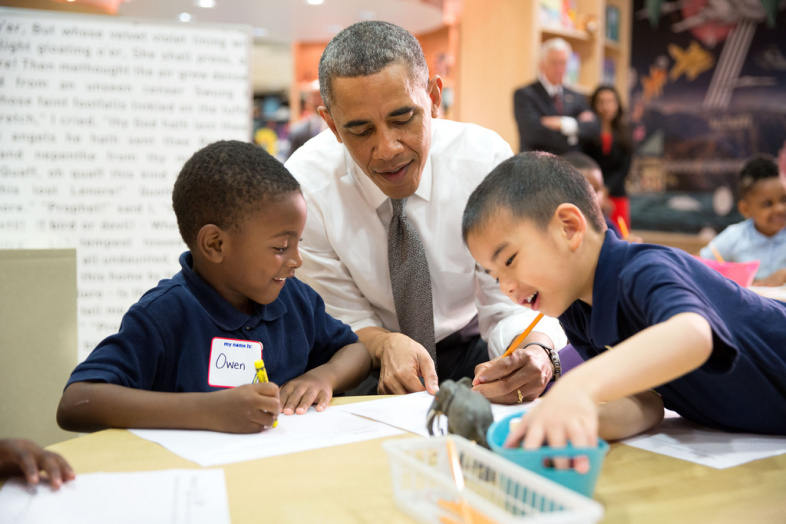

(Source: Pete Souza)

I am not against excellence. I just think it’s over-rated as an aspiration. In fact, I think aspiration itself may be over-rated.

When I see excellence—when I’m competent to recognize it (and in many fields, like science and opera, I am not)—it is thrilling and heartening, as a friend once said, to realize what the species is capable of at its best. Excellence is by definition rare, and the kind of excellence that thrills, rarer still. It is not just a little better than “good.” It’s way better in a way that stuns ordinary expectations, and expands them. So the more excellence there is in the world, the better.

| This article was originally published by Working-Class Perspectives and appears here by way of special arrangement with that publication’s editors. |

But that doesn’t mean we should pursue it. First, doing so has a strong tendency to lead to a wicked combination of hypocrisy and lower standards. As a professor at a fourth-tier university that has recently scrambled up to the third tier, I’ve sat through a lot of commencements where speakers have tried to inspire graduates to “always pursue excellence, and never settle for second best.”

I love that university in an immoderate way, and have from my first day of teaching there. I love the students too. But they are not pursuing excellence, and they’ll have to work very hard, with great discipline and persistence, to get something close to “second best.” I’m confident that most of them will, that their education has improved their chances, and that most of them will appreciate getting into the neighborhood of the second best, but I fear for those who genuinely pursue excellence and even more for those who think they have achieved it.

Second, there is no evidence that pursuing excellence actually leads to it. Based on the testimony of many great artists, for example, excellence more often happens if not by accident, then through a combination of circumstances where the conscious pursuit of excellence is not one of the circumstances.

An extraordinary talent or “gift” is often one of those circumstances, as is determination and focus in pursuit of a specific goal – curing cancer or perfectly expressing a complex feeling or thought in the hopes that others might recognize it. “Things just all seem to come together” in a way—luck, strategic help from friends and colleagues, a muse or collection of muses—that is beyond the will of the artist or scientist or carpenter or statesperson.

My main gripe with pursuing excellence, however, is the way it necessarily encourages competition among individuals. Excelling means measuring ourselves against others, and this tends to undermine our focus on doing a good job. That is, trying to excel can distract us from what we’re doing and how we’re doing it, as we pause to rank ourselves against others doing something similar.

Most of us figure out fairly early in life that excellence is not in our range of capability, but the drumbeat of a culture that insists on excelling and not being second best leads us to try anyway. Sometimes this trying makes us better than we might otherwise be, but more often, I’m convinced, it leads to an unhealthy concern to out achieve others, to feel diminished by their accomplishments, and to be constantly reevaluating our self-worth in relation to our perception of others.

This leads to a certain broken sadness, if not clinical depression, alternating with an exaggerated and exaggerating tooting of our own horn—ostensibly to impress others, but mostly to approve ourselves. This high-stakes competitiveness with others takes our eye off the ball, undermining whatever chance we may have of achieving excellence, which in most human endeavor requires a little help from our friends.

|

The more unequal a country is, the higher the aspirations children report and the larger the gap between aspirations and actual opportunities.

|

Though probably overdrawn in this brief space, such a phenomenon is characteristic, in my view, of professional middle-class culture in early 21st century America.

The original ethic of professionalism was to establish certain minimum standards for an emerging profession and then gradually improve them. It was a collective endeavor to elevate the level of the profession, which elevation would help not only those in the profession, but everybody—indeed, it would advance the species. (These were standard claims of middle-class professionals in the Progressive Era. See From Higher Aims to Hired Hands for how even the professionalization of business management was originally rooted in such claims.) Status was always an (overly) important concern, but it wasn’t atomistically individualized the way it is now. Today’s resume-builders often actively disrespect their profession in order to individually stand out in their superior pursuit of excellence.

Fortunately, working-class culture is still a healthy, if beleaguered, antidote to the dominant middle-class one, and I have been fortunate to spend my life teaching working adults who “just want to be average” in a program that is reliably good at helping them achieve that goal. Working hard and doing a good job, “pulling my weight” and “doing my part”—not pursuing excellence—are the core motivating values that working-class people feel bad about when they don’t live up to them. Being outstanding is not only eschewed, it is actively feared, and the culture has subtle and not so subtle sanctions against it.

The problem is not only that the dominant middle-class culture is more dominant than ever or that its characteristic individualism is turning into an other-directed caricature of itself. Rather, the extreme levels of income inequality we have now reached make the working-class way dramatically more economically punishing.

My students often have to at least mimic a phony pursuit of excellence if they are to provide for themselves and their families. The worse things get, the more they are told not to sell themselves short, to set their sights high, to aspire to become whatever you want to be (unless, of course, you just want to be yourself). Our crazy levels of economic inequality also foster a winner-takes-all culture. Winners should get not just all the honor and the glory, but most of the money and the power. Losers should aspire to do better.

Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett in The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger document the devastating effects income inequality has on everything from reduced social mobility and health (both physical and mental) to higher levels of crime, teen pregnancy, infant mortality, and drug and alcohol addiction. One of the most surprising results they found is that the more unequal a country is, the higher the aspirations children report and the larger the gap between aspirations and actual opportunities.

Conversely, the more equal a country’s incomes are, the more children report low aspirations—while doing better in education and all other indicators of social well-being. The correlations Wilkinson and Pickett found among the richest countries in the world allow the conclusion that high aspirations lead to lower educational achievement—that is, that pursuing excellence actually makes a society less likely to achieve it.

This accords with my own observation and experience. A culture that encourages people to “work hard and do a good job” leads to greater personal integrity, better mental health, and higher actual performance levels than the false counsel to “pursue excellence and never settle for second best.”

Jack Metzgar is a core member of the Chicago Center for Working-Class Studies.

0 Comments