(Source: Too Much)

The future just keeps getting brighter for Americans with unique specialties.

Randy Stearns has one such specialty: “home-tech integration.” Stearns helps people install and maintain high-tech gadgets. But we’re not talking “geek squad” and hooking up home networks here. We’re talking rich people—and electronic toys that can cost more than houses.

| This article was originally published in Too Much and appears here by way of special arrangement. |

Stearns offers “24/7 white glove” service for clients who typically pay between $150,000 and $450,000 per project. These affluents get plenty for their money. Call Randy and you, too, could end up with a home monitoring system that sends out alerts whenever your wine cellar temperature rises too high.

Annual sales in luxury home-tech integration, Stearns estimates, are going to nearly double—to $3.7 billion—by 2016. He may be underestimating his potential market. America’s rich, two top economists revealed last week, are actually getting richer faster than almost anyone thought possible.

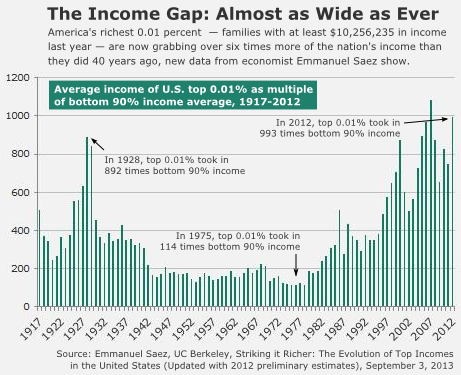

Last year, report Emmanuel Saez from the University of California Berkeley and Thomas Piketty from the Paris School of Economics, the incomes of America’s top 1 percent—families that took home over $393,941—shot up just under 20 percent over the year before. America’s really rich, families in the top 0.01 percent, saw their incomes soar by over 32 percent.

The just over 16,000 families that make up our top 0.01 percent finished up last year averaging $30,785,699 in income each.

And the rest of America? The incomes of the nation’s bottom 99 percent rose all of 1 percent last year. Since 2009, bottom 99 percent incomes have barely bumped up at all, just 0.4 percent on average, after taking inflation into account.

Saez has a stat that puts the matter even more starkly. America’s top 1 percent, he notes, has “captured 95 percent” of all income gains over the first three years of the recovery. Overall, since 1993, top 1 percenters have grabbed “just over two-thirds” of total family income growth.

This massive surge at the top has—no surprise—significantly hiked the share of national income that’s flowing into the pockets of America’s most comfortable.

For most of the middle of the 20th century, America’s most affluent 1 percent took in less than $1 of every $10 in national income. In some of these years, the top 1 percent share even dipped under 9 percent.

Those days now come across as almost mythic ancient history. In 2007, the year before the Great Recession hit, the share of the nation’s income the top 1 percent claimed hit 23.5 percent, or nearly $1 out of every $4.

This top 1 percent share did dip with the Great Recession, down to 18.1 percent in 2009. But the “recovery”—for the rich—has since then been almost total. Last year, the top 1 percent income share jumped back to 22.5 percent.

| Fact: America’s top 1 percent has “captured 95 percent” of all income gains over the first three years of the recovery. Since 1993, they have grabbed “just over two-thirds” of total family income growth. |

We have come, as a nation, almost full circle back to the deeply unequal America of the late 1920s. That America’s deep economic divides ushered in the Great Depression of the 1930s.

We finally ended the Great Depression, Berkeley’s Saez points out, by nurturing a set of institutions that narrowed the gaps between America’s wealthiest and everyone else.

The two most fundamental of these institutions: a vibrant labor movement that established new social norms about fair pay and a steeply progressive tax system that subjected the nation’s wealthy to tax rates that topped 90 percent on income over $400,000.

These two institutions have both withered over recent decades, and the Great Recession hasn’t yet done much to reverse that withering.

Recent equalizing policy changes—like the higher federal income tax rates on the rich that came in earlier this year—remain, notes Saez, “modest relative to the policy changes that took place coming out of the Great Depression.”

And this reality has insightful observers like the Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s Jay Bookman deeply worried. The nation’s most affluent 10 percent, Bookman notes, took in just a third of the nation’s income four decades ago. The top tenth last year, for the first time ever, took in over half the nation’s income dollars.

“Great concentrations of wealth” like this, Bookman wrote last week, “create great concentrations of political power and distort the terms of debate.”

How distorted has our debate become? Our lawmakers, observes Bookman, now see no problem cutting food stamps at the same time they refuse to raise taxes higher on America’s ever-richer rich “because that wouldn’t be fair.”

The bright side? In an America growing more unequal, people like Randy Stearns won’t have any trouble finding clients.

Sam Pizzigati is an Associate Fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies and editor of Too Much: A Commentary on Excess and Inequality.

0 Comments