On this date in 2017, members of the alt-right, neo-Confederates, neo-fascists, white nationalists, neo-Nazis, Klansmen, and various right-wing militias marched in Charlottesville, Virginia, carrying semi-automatic weapons and chanting racist and antisemitic slogans. Civil rights activist Heather Heyer was killed and dozens injured when a car driven by a white supremacist slammed into a crowd of protesters. BlacKkKlansman, Spike Lee’s fierce and brilliant satire on American racism, is reviewed here by the award-winning poet and critic Cyrus Cassells.

The good news for movie fans is that Spike Lee’s rousing BlacKkKlansman, the winner of this year’s Oscar for Adapted Screenplay, is his most fluid and satisfying film “joint” since the era of Summer of Sam and Do The Right Thing. In a way, BlacKkKlansman represents the real-life version of the uproarious Black and Jewish revenge fantasies that bad-boy director Quentin Tarantino staged so elaborately in Django Unchained and Inglourious Bastards. Based on a memoir by former Colorado Springs police officer Ron Stallworth, Lee focuses on Stallworth’s unlikely (and later deliberately censored) escapades as a Black undercover cop in the 70s who, in ingenious fashion, managed to infiltrate the Ku Klux Klan (with the aid of a fearless Jewish colleague as his decoy), by cleverly mimicking a white man’s voice over the phone. The ploy recalls a key moment in the irreverent Boots Riley comedy, Sorry to Bother You, when Danny Glover as a veteran salesmen advises LaKeith Stanfield, playing a phone-selling rookie, to make sure to “use your white voice.”

BlacKkKlansman is a classic believe-it-or-not trickster’s tale, and Lee plays comic variations on timeless themes of Black accommodation and assimilation, upping the sociopolitical stakes by weaving in snatches of Gone with the Wind (the film starts with a full-out recreation of the famous panoramic sweep of all the wounded Rebel soldiers lying stricken in the streets of Atlanta) and Birth of a Nation to represent noxious Dixieland myth-making that routinely manufactures racism as true-blue patriotism and heroism. The always up-for-anything Alec Baldwin shows up as flagrantly racist commentator named Kennebrew Beauregard, who proclaims “we’re cleansing this country of a backwards race of chimpanzees,” as he invokes “Biblically inspired white rule,” “Jewish supremacism,” and revels in spouting racist filth: “we had a great way of life until the ‘Martin Luther coons’ of this world.”

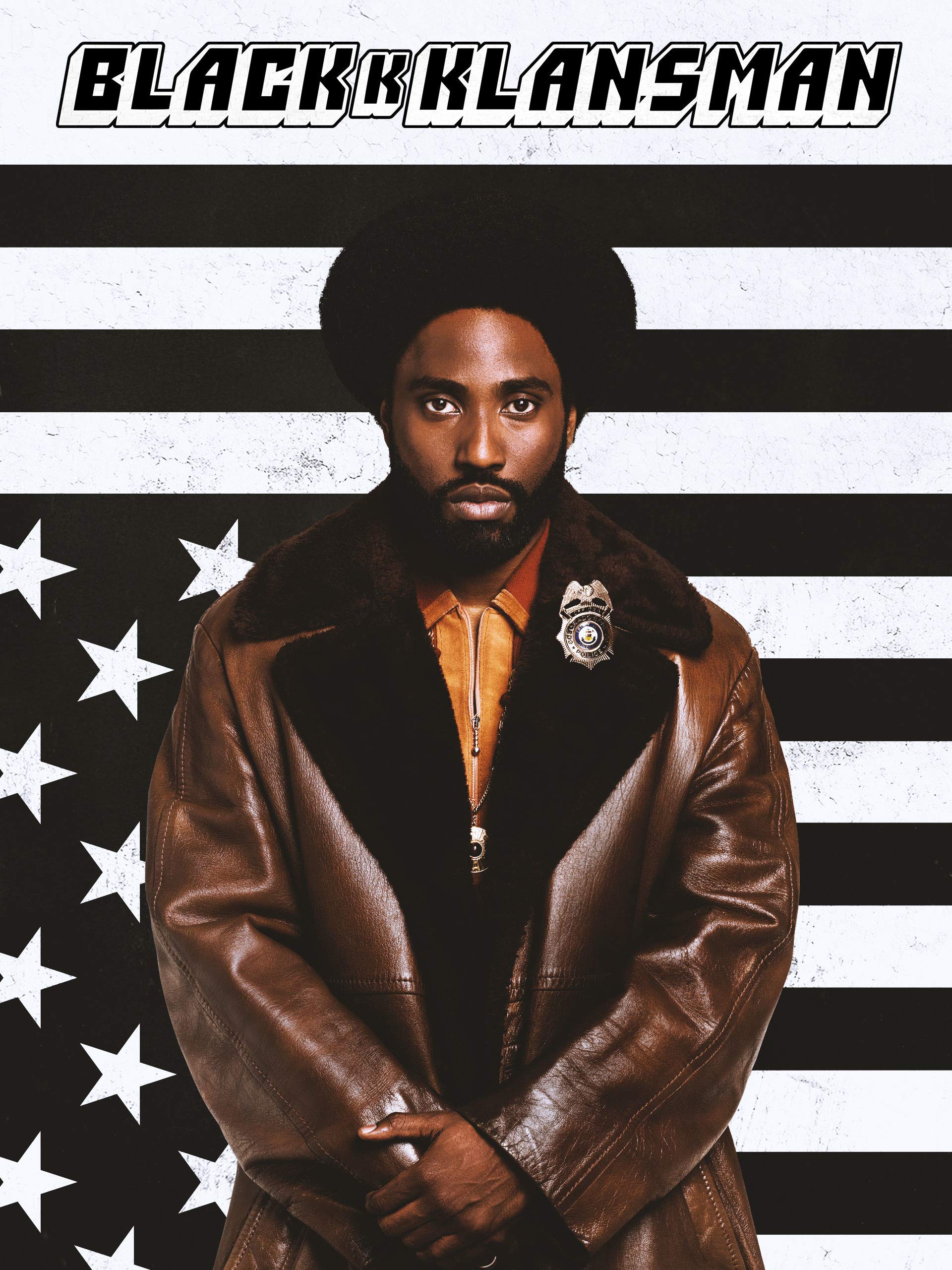

Ron (played with seriocomic agility by John David Washington, who sports a dapper, picture-perfect Afro) spells it out for us: “I feel like I’m two people all the time,” suggesting the great 19th century African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar’s classic poem, “We Wear The Mask.” Stallworth basically functions as the Jackie Robinson of the Colorado Springs police force; he’s routinely demeaned at first, constantly hectored and disrespected by colleagues and superiors until he devises his go-for-broke plan to take down the local chapter of the Klan.

Ron, not surprisingly, is assigned by his superiors to a Black student rally and goes undercover as a fist-raising Black activist—a result of police jitters about “radicalism” taking root in the community, as the press and public fell “hook, line, and sinker” for the FBI’s shamelessly contrived “the Panthers are a menace to society” smear. Flying in the face of his mostly effective spying, Ron ends up sympathizing with the protesting students and falling for Patrice (Laura Harrier), an ardent organizer who’s both adorable and a righteous sister—in the firebrand mold of a young Angela Davis: “Pigs—what else should I call them?” and “Are you down for the liberation of Black people?” BlacKkKlansman captures, with outright nostalgia and unabashed affection, the 70s spirit of Afrocentric camaraderie (in loving close-ups, Lee lingers on the glow of the young activists’ earnest faces, giving them an appealing, burnished beauty, reminiscent of Rembrandt’s portraiture) and happily nails the catchy jargon of the era: “Right on! Power to the people!” The lighter, bubblier moments of Ron and Patrice’s intricate courtship (blissfully comparing Blaxploitation figures) make for an upbeat, offhand counterpoint to the movie’s creepy, right-inside-the Klan component.

BlackKkKlansman is quite nimble in critiquing and counterpointing current alt-right fervor by conveying the mainstreaming of the Klan in the 70s. A scheming white couple (gun-toting Holocaust deniers and Klan conspirators) is so “cheese-whiz and cracker” banal, they’re like gleeful, greedy consumers on a sitcom or an out-of-control game show, except they’re talking about offing their fellow citizens. The Grand Wizard himself, David Duke, shows up, clean-cut and polyester-suited, like a baby-kissing political prince, and laments to his followers: “No one wants to be called a bigot anymore.” On the timeless theme of the test of authentic whiteness, Duke insists (as if he were employing some kind of shibboleth out of the Bible) that he can identify a white person by their telltale pronunciation of the letter “r.”

Spike Lee’s Bamboozled, a blazing guns satire that featured a sold-out Black writer and a blacker-than-thou white executive who helmed an updated minstrel show (a TV ratings mega hit!) had rollicking scenes of racial satire that, in the year 2000, practically sent the white press into a coma; a “box office bomb,” Bamboozled came and vanished from theaters that initial fall of the century with considerable speed, yet for those of us who saw it, Lee’s masterly end-credit montage, featuring minstrel and mammy paraphernalia, remains one of the finest end credit sequences in all of film. Almost twenty years ago, when Bamboozled first screened, the complacent (and mostly clueless) media didn’t have the slightest penchant for dissecting race, but the times have caught up with social critic and sometime satirist Spike Lee. I admired his brash rethinking of the ancient Greek comedy Lysistrata in Chiraq, his previous film. Maybe Lee’s the man to tackle Man Booker winner Paul Beatty’s relentlessly hilarious takedown novel The Sell-Out.

I know a savvy African-American monk and inveterate Spike Lee fan who insists Americans in general can’t handle much satire and can’t often tell if the mood-shifting, genre-splicing Lee is being real or pulling the audience’s leg; for instance, in Bamboozled, Damon Wayans was so stiff and mannered as spiritually indentured screenwriter Pierre, it was hard to tell if he was merely delivering a fidgety, robotic performance or meant to be a blatant parody of a pretentious Black intellectual.

Among BlacKkKlansmen’s several pluses: a lively 70s period soundtrack, enhanced by original music from multiple Grammy-winning jazz trumpeter and composer Terrance Blanchard (whose work here was justly Oscar-nominated for Best Score), and a fine, unfussy turn by Adam Driver as Flip Zimmerman, the Jewish decoy who ventures deep into the poisoned and lunatic world of the Klan. Driver has been on an impressive career track, having already worked with Woody Allen, the Cohen Brothers, Jim Jarmusch and Martin Scorsese, and now, acting for Spike Lee, as a secular Jewish cop brought face to face with fierce anti-Semitism, he delivers his most subtle and complex performance to date, garnering, among several other nods, an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor.

The film opened wide in theaters on the one-year anniversary of the infamous white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, and ends with unsettling footage of the “alt-right” march and of the white extremist runaway car attack that ended activist Heather Heyer’s life. The present day shift is so jolting that it dilutes, to a degree, the exhilarating Mission Impossible derring-do and the Black and Jewish tricksters’ triumph of the scenes just before it. Lee’s refusal to end the film on a high note of comic triumph suggests the preacher/teacher in him, ever prone to grab you by the lapels. For instance, as the counterpoint to the KKK ritual initiation, having the iconic Harry Belafonte deliver a speech about the Birth of a Nation era mutilation and lynching of a retarded teen accused of sexual assault in Waco, Texas, is maybe upping the ante too much.

I’m reminded of the cover of Yoko Ono’s Season of Glass, an austere still life featuring a water glass juxtaposed with John Lennon’s ruined eyeglasses; it’s the knife-keen album Ono delivered after Lennon’s murder happened right on their Dakota apartment doorstep. If you look closely, you can find flecks of the slain singer’s blood on the frames. When people were incensed at Ono’s use of Lennon’s murder scene specs, she responded: “Did they think it wasn’t real?” Both Spike Lee and Yoko Ono would insist the blatant shock factor in their work is justified, because the ritual burning cross, the postcards of the lynching tree, and the bloodstains on the splintered glasses aren’t going away.

Cyrus Cassells, a poet and professor of English at Texas State University, lives in Austin.

0 Comments