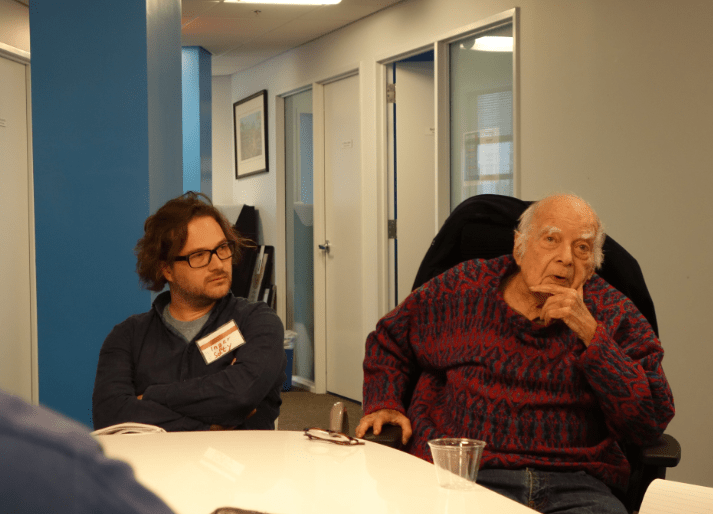

The American sociologist and journalist Norman Birnbaum died in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 4, 2019. A prolific author and revered scholar, Norman was an adviser to leading politicians on both sides of the Atlantic. His life and work were shaped by the seminal events of the 20th century, from the rise of the Nazis to the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of Soviet communism. His friend Sidney Blumenthal delivered this eulogy at a memorial service held on March 1 at the Georgetown University Law Center.

I am here today to speak about Norman, but how I wish I could speak today with Norman. He was engaged with the urgent questions of the day virtually unto his last day. His mind was as probing as ever, his reservoir of learning as deep, his wit and irony and his senses of paradox and possibility were as acute as ever. I can still hear and see him.

You remember him, too. A momentous issue would be suddenly raised, the latest travesty. Norman would begin to speak, but with a pregnant pause. His eyes would focus. The marshaling of his mental powers would be visible in that flickering moment of silence. He was drawing on his vast erudition, his accumulated wisdom and experience, and his acquaintance over a lifetime with the great, near-great, and not-so-great on two continents. “Well,” he would stammer, and then would follow a stream of words rapidly building into a mighty river of current and detailed knowledge of transatlantic politics and personalities, references and quotations from interesting and relevant characters he had known, citations from history, and, if you were lucky, a sharp and funny little story animated by his gesticulations. Norman would laugh himself. When Norman laughed, his whole body would shake up and down. Awaiting your response, he would look directly at you—almost stare at you—and say, “Hmm?” He was the most serious and the most mirthful man I knew.

Norman was for all intents and purposes a member of our family. At the seders at our home, around our table, to celebrate the exodus from Egypt, the festival of freedom, Norman would recount for us his reminiscences of what it was like, as a young man, to experience the fear of the rise of fascism and Nazism. From generation to generation is the injunction to Jews to pass down a moral understanding of the past that informs the present. For us, Norman was and remains an indispensable part of that chain of living history and ethical responsibility.

There was not an election night at our house from which Norman was absent. He arrived in 2012 on our doorstep just as President Obama’s reelection was declared with a champagne bottle in hand. Four years later, as the catastrophic results were announced, sitting in our living room before the television, he refused all drink. And just last November, at the moment the Democrats won the House, he held out a glass for champagne—and a refill.

Norman’s story was an unlikely but emblematic American one. He titled his memoir From the Bronx to Oxford and Not Quite Back. It was a Bronx story, a London and Oxford story, and a Berlin—and Madrid, Paris, Rome, Amherst and Georgetown—story. Norman was an iconic New York intellectual, yet too cosmopolitan to be simply a New York intellectual. He transcended categories.

In his book The Radical Renewal, published in 1988 and written partly while he was at the Wißenschaftskolleg in Berlin, he wrote about the difficulty people had in pigeonholing him: “Not so long ago, a Jesuit friend asked me why I had not become a neoconservative. ‘After all,’ he said, ‘You are from New York, you admired Trotsky, and, of course, you are Jewish.’ ” “These,” Norman answered, “may be necessary conditions for neoconservatism, but they are not sufficient.”

He explained that he left New York to attend Williams College at the age of 16, was “active in radical politics” but “never belonged to either the American Communist Party or any variety of Trotskyite group. I do not wish, then, to deny or repudiate my past.” He added, “Finally, I have retained enough of my Jewishness to interpret the world as incomplete. We are in this world not to justify it, but to fulfill it. Good intentions are not enough. We need ideas that are complex and deep as well as critical.” Norman was referring to the Jewish injunction of Tikkun Olam, to repair the world, to which he devoted himself.

Norman was unique, one of a kind. He was not simply multidisciplined; he was a multidiscipline—master of history, literature, and sociology, in a style that was a unique amalgamation of a Bronx boyhood and a New England education, combining the manner of an Oxford don, the method of a German social scientist, and the passion of an Old Testament prophet. He was at once Olympian, Talmudic, and Jesuitical—and he encompassed in his rigorous secular outlook prophetic Judaism, social Catholicism, and dissenting Protestantism.

Norman was a man of the left who was unbound by its milieu—or any single milieu. He wasn’t limited by any dogma, and he especially disdained any dogmatic cast of mind. He was far too cosmopolitan. He was an academic with a courtly manner who chafed at any narrowness or parochialism. Above all, he had the qualities of a great teacher with the humility and patience to explain to those who knew much less without the slightest condescension on his part. He was endlessly generous, approachable, and encouraging. He could not help but be a teacher. He had taught at the greatest universities in the world, but in our neighborhood recently, he delivered lectures on European affairs to the senior citizens of the Glover Park Village Association, where he was enormously popular.

Norman was a man of parts and all of a piece. He was a globe-trotter, an inquiring thinker, an activist, and a bon vivant. Imagine if Max Weber had a wry sense of humor, Talcott Parsons had a touch of the boulevardier, and Antonio Gramsci sparkled at dinner conversation.

Norman was far too modest about his accomplishments. In retrospect, he played an important role in an important time. It was Norman who brought modern critical sociology to Britain. Norman was not a small-time empiricist operating with arcane statistics. He shaped large ideas to current affairs to reach large conclusions about social structures and forces. While he was at the London School of Economics and Oxford, he joined with the innovators of the New Left, and when he returned to the United States, he was instrumental in creating the transatlantic link to the movement.

Norman’s friends, acquaintances, and enemies would fill an encyclopedia of the intellectual history of the 20th century. Any understanding of Norman would require familiarity with the spectrum of essays, momentous and obscure, that appeared in the magazines and journals with which Norman was affiliated as an editor or contributor—Partisan Review, New Left Review, Encounter, Commentary, The Nation, to name just a few.

As a boy he literally sat at the knee of Eleanor Roosevelt at a summer school on Campobello Island. He was sponsored to teach at Oxford by Isaiah Berlin, befriended Iris Murdoch, Eric Hobsbawm, and Ralph Miliband, among many, many others. He was a colleague of the American New Left radicals, taught at Harvard with Henry Kissinger, was an associate of Irving Kristol and Norman Podhoretz, but also of Arthur Schlesinger and Michael Harrington. He advised Willy Brandt, François Mitterrand, and Ted Kennedy. And that only scratches the surface.

The arc of his work reflected his persistent attitude: pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will. His book titles told it all: The Crisis of Industrial Society. After Progress. The Radical Renewal.

Well, almost all.

There was, of course, another side to Norman. Norman the guide to social developments, the political theoretician and activist, the man of the left, thinking deeply about the problems of inequality, was also an epicurean. He once invited me to lunch at his house, asked me to bring my dog, Pepper, my constant companion, and inquired what Pepper would like to eat. Anything, I said. Norman, who was always thoughtful, cooked a large roast beef and laid a full plate of carefully cut slices on the floor. Norman once solemnly addressed Pepper, to establish his exact relationship, saying, “I knew your predecessor.”

Norman also did like to dress well. In his memoir there is a photograph of Norman looking very serious and wearing a garish striped shirt. The caption reads: “In my study in Amherst, wearing a favorite Italian shirt I purchased when consulting with the Italian trade unions and the Communist Party. I always got myself stylish shirts in Italy, which were much envied by my then friend, Norman Podhoretz.”

Norman’s range of contacts, as I discovered, was more than extraordinary. In 1986, I was a reporter for The Washington Post and in Berlin for a conference. Norman was spending the year there as a visiting scholar. Over lunch, he explained that he had been banned from entering East Berlin because of his associations with certain dissidents there. Would I go to see them? That night, carrying a bottle of schnapps Norman told me to bring, I passed through the Friedrichstraße crossing, jumped on a tram, got off at the stop Norman indicated, and found myself lost in near darkness. Asking directions, I finally located the apartment of his friends, a young couple with small children. We had a long, intense night of discussion about politics, philosophy, American movies, and Norman. Then I took the tram back. I was followed by the Stasi, stopped at the Berlin Wall, and for an hour detained in a cell. The next night, Norman treated me and his daughter Antonia to a celebratory dinner at a restaurant appropriately named Exil. As it happened, in fact, those two individuals and their fellow dissidents were the leaders of a group called Neues Forum, the organization that three years later led the demonstrations that brought down the Berlin Wall and overthrew the East German regime. The single American they most admired, trusted, and considered an intellectual light was none other than Norman—a man who could discuss European social democracy for hours on end and whose own free and fearless manner, especially in his outspoken left-wing ideas, personified to them what lay on the other side of the wall. It was Norman who tore down that wall.

“Avoidance, falsification, trivialization mark our encounter with past and future,” Norman wrote in The Radical Renewal. “The rejection of illusion implies a human capacity to endure truth in the present and to act differently in the future.” Writing in 1988, he prophetically wrote:

Modern authoritarianism is not subtle, but it is omnipresent. Its new form is not obeisance to human authority alone, but a reification of the present, a refusal to believe that human institutions could be different. To the argument that reality is in fact menacing, there is no obvious answer. In any event, we may see how far we have come, or how deeply we have descended. The thinkers who proposed the idea of the authoritarian personality, and those who then developed it, supposed that there was something pathological about humans who did not walk upright. Cringing has now become the norm. The struggle for an educated citizenry is a struggle against spiritual proletarianization. In the end, we may well have to reintegrate familiar categories (class, gender, race, and religion) in an unfamiliar fashion. Rather than seeing these as segmented or separate aspects of our society, we may come to understand them as a connected series of conflict-laden differences. It is a pity that there are so few authentic conservatives around to join us. If we are to reenact, in contemporary terms, the early American belief in a republic of virtue, we shall have to find a new philosophical basis for both social inquiry and politics. That is a matter for further reflection.

In that last line, I can distinctly hear Norman’s inimitable voice.

Ultimately, after much reflection, Norman wrote his memoir. When Norman’s era had passed, he continued to keep his tradition alive. He memorialized it, preserving it for the future. His memoir is intimate, fresh, and precise. Norman presented a cavalcade of 20th-century intellectual transatlantic life. His book contains delectable gossip, paints portraits of the characters who dominated academia and politics at midcentury—the grand and grandiose, and offers clear analysis of the state of political affairs of the time and profound insight into the nature of history, sociology, and religion. Norman left us his voice.

At the very moment of Norman’s passing, a new generation has emerged that is dedicated to many of his ideals and values. “American historians,” Norman wrote in the conclusion of his memoir, “frequently refer to a search for a usable past. I came to cultural and political awareness in the terrible year 1938. Ideals and illusions have claimed my attention since—in no linear way. I was right to title my last book After Progress, hesitant in it to do justice to the title. I will give the theme one last try.”

Norman has left us more than his extensive body of work, even the more than 200 articles he wrote after his retirement. His teaching has not ended. He has left his decency, his legacy of education, his example of endurance, his spirit of repairing the world, from generation to generation.

Sidney Blumenthal is the author of All the Powers of Earth: The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln 1856–1860, the third of his five volumes on Lincoln, to be published in September.

An outstanding share! I have just forwarded this onto a coworker who had been doing a little

homework on this. And he actually ordered me breakfast simply because I stumbled upon it for him…

lol. So let me reword this…. Thank YOU for the meal!!

But yeah, thanks for spending the time to discuss this matter here on your

blog.

Just wanna remark that you have a very decent website,

I the pattern it actually stands out.

Useful info. Fortunate me I found your website unintentionally,

and I’m surprised why this accident didn’t happened earlier!

I bookmarked it.