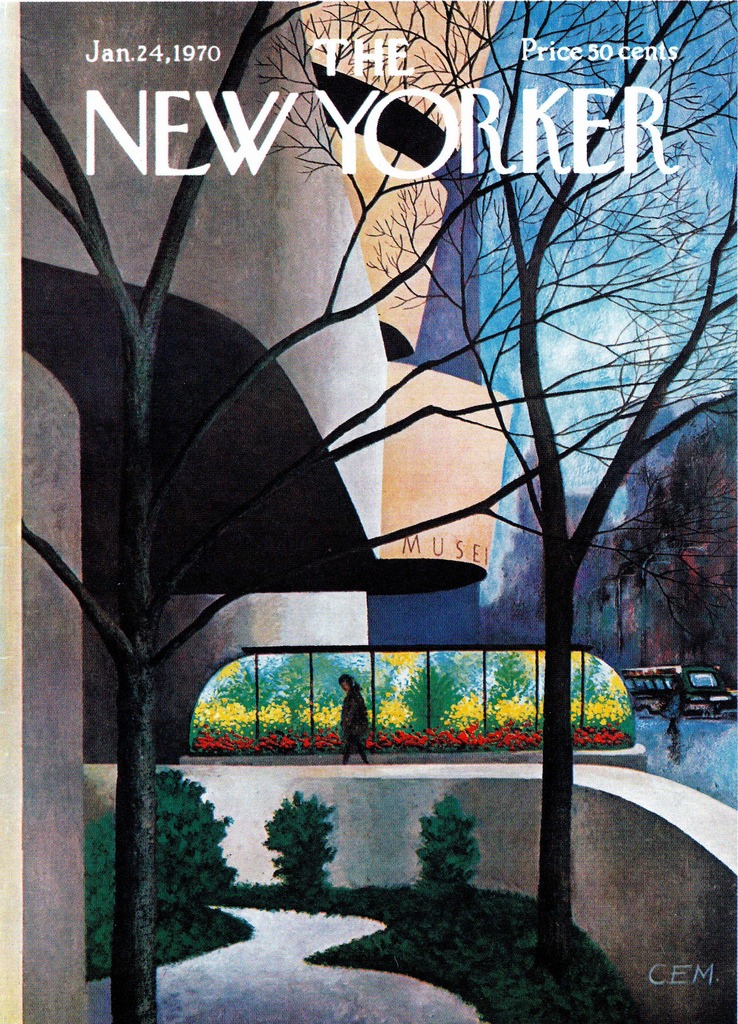

Dubbed the Gentle Despot of The New Yorker, William Shawn was the shy, strong-willed, nurturing and eccentric steward of America’s leading magazine and mentor to generations of the country’s most gifted writers. In this short account of his own time in Shawn’s orbit, written in January, 1993, the critic Jacob Brackman depicts Shawn’s unconditional support for his writers alongside his idiosyncratic engagement with reality.

A friend called to tell me William Shawn died. He’d been the editor of The New Yorker magazine from 1952 until 1987. A quarter-century ago—through my 20s—he was the most important man in my life. To say he occupied a like place in the hearts and minds of hundreds of writers would be no exaggeration. At least 100 books are dedicated to him.

When I was 21, fresh out of school, Shawn made me an offer I couldn’t refuse: a small office at “the magazine,” with a typewriter and pencils sharpened daily; a weekly “draw” of whatever amount I thought I’d need. If they bought something of mine, and the purchase price put me ahead, I could at any time cash out the difference. No one would ask me what I was working on or when I’d be finished. This was a dream deal, and the delicate, courtly man who elucidated such “customs” to me might as well have been my fairy godfather. For reasons unknown, he’d decided to touch me with his wand and spare me all the usual dues.

Shawn was already in his 60s. His warren then housed many writers much older than me who, it was said, hadn’t published anything in decades. I got the impression no one was ever dismissed. Certainly no one left of his own volition. Apparently, being “on staff” was a lifetime sinecure. My blessed and enviable situation, I dimly intuited, could be my gradual undoing.

I was curious, therefore, when introduced one day to a writer about 15 years my senior, who “used to be on staff.” He’d stop by now and then to meet a former colleague for lunch. We’d chat by the water cooler. It was not until a few years later, though, when he told me he was moving back into his old office, that I made bold to ask how he’d come to leave. He explained that shortly before we had met—when he was waiting to hear about a reporting piece he’d submitted—he’d encountered Shawn in the hall, and Shawn had asked him if he’d thought about what he was going to do next. He had interpreted this to mean his piece was bad and he’d been fired. He cleared out his office and quit the building that very afternoon.

Just the other day, however, turning a corner on the 17th floor, he’d again bumped into Shawn, who asked him the same question as before. Except this time, Shawn had added, “We’ve missed seeing anything from you for a while.” Then he’d lifted his hand in a tiny gesture that clearly signified “not that I mean to put any pressure on you.” As Shawn continued on down the corridor, the writer realized he’d been rehired or, rather, that he’d never been fired in the first place. Shawn had been evidently unaware of his absence as anything more than a normal delay in handing in a next article. Directly, this writer informed the reception that he’d be returning to the office next Monday, and he called the switchboard to say he was back at his usual extension.

For a company so large and rich, The New Yorker had strangely little in the way of middle-level management. It was virtually a one-man shop. A huge power gap existed between Shawn and his seconds-in-command, who were there not to formulate editorial policy but to help put out exactly the magazine he wanted—not catering to any relationship, simply producing a magazine he himself would enjoy reading, and which therefore reflected his gentility, his thoroughness, his humor, the range of his intellect and enthusiasms.

“Assignments” would come from him not even in the form of suggestion, but rather as a whispered question. “Am I catching you at a bad time, Mr. Brackman?” “Is this one for you?” It was hard to comprehend how someone so powerful could be that solicitous or spend that kind of time with me, going over prose, line by line. I remember his nodding when I’d complain about trouble I was having with some essay, fairly squinting with compassion, translucently pained on my behalf.

Some people saw in Shawn an autocrat with exquisite manners. At a certain point, I fell into this misapprehension myself. I felt his sensibility overwhelming my own. I felt in danger of being swallowed up, and I left the magazine. It was a small-minded way of reckoning his transcendent courtesy.

On one occasion, years earlier, in the full-out craziness of late ’67, tormented by an imagined “emergency,” convinced there was nowhere else to turn, I rang the Shawns’ doorbell at 3 a.m. As they sat with me in their living room, bathrobes over pajamas, talking me down, it slowly dawned on me that I might be imposing. I backed toward the door, apologizing for having disturbed them at this inappropriate hour. “No, no, no, dear,” Mrs. Shawn reassured me, as her husband nodded. “We have this all the time.” In a taxi heading back downtown, I understood that reassurance as something more than tact. Writers whom they knew had been going off the deep end for 40 years. And when they did, they turned naturally to Mr. Shawn. As I’m sure they continued to do until he died.

Jacob Brackman is a journalist, screenwriter and lyricist whose varied career has included posts at Newsweek, The New Yorker and Esquire. His screenwriting credits include King of Marvin Gardens and Times Square, and as a songwriter he has collaborated with several artists, most notably Carly Simon.