“Not a dime’s worth of difference,” was how Alabama Governor George Wallace described the Democratic and Republican Parties of the late 1960s, when he led the short-lived American Party.

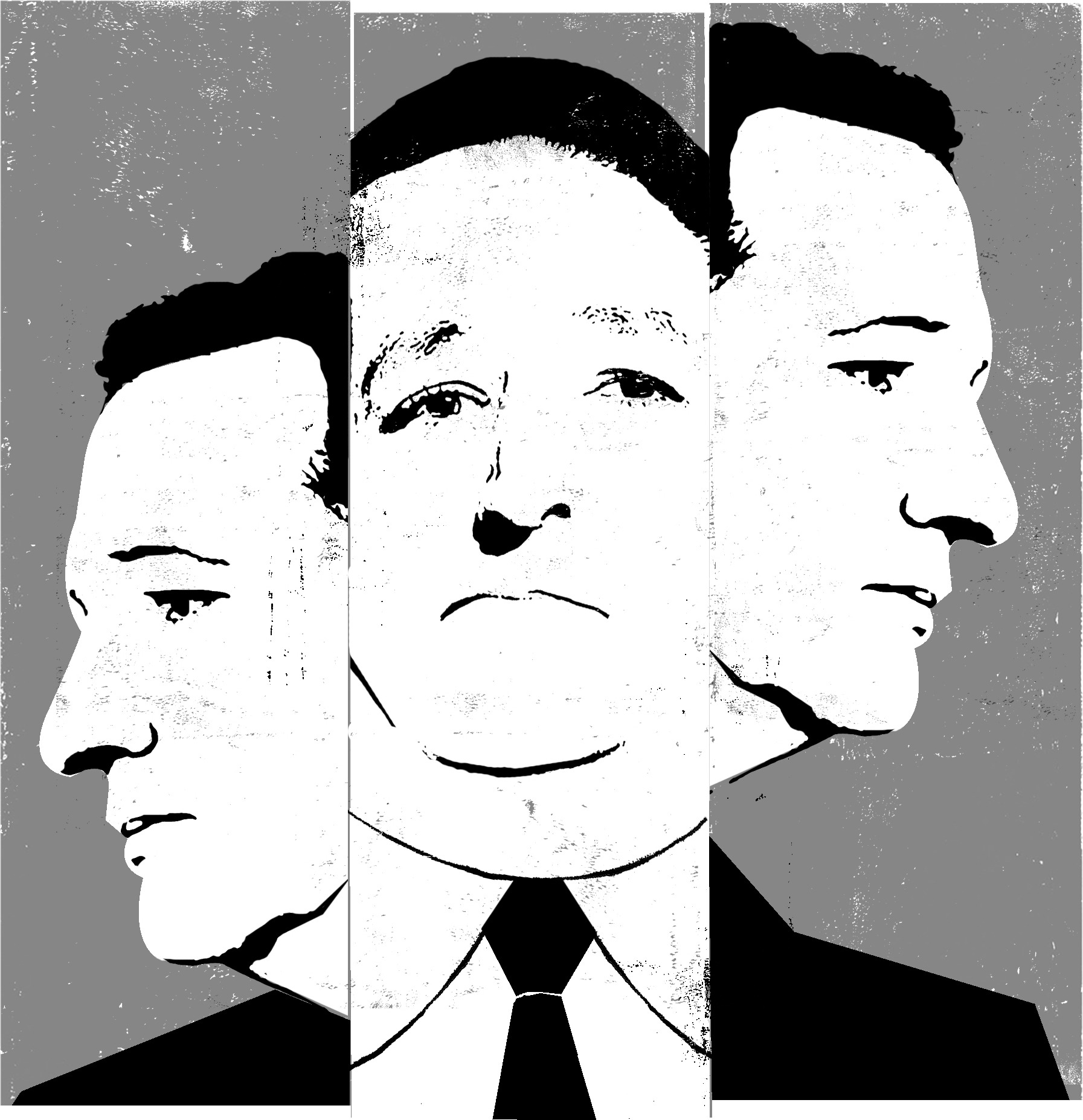

The same can be said of Ted Cruz and Donald Trump as they compete for the voters Richard Nixon saw as key to a Southern Strategy and a permanent Republican majority in the South.

The difference between the two Republican candidates is stylistic. Trump is the narcissistic vulgarian incapable of restraint while in front of an audience; Cruz the cerebral and abrasive ideologue who abandons restraint when it suits his purposes (Obama is “treasonous” and a “clueless socialist”). Their principles and policy goals, absent harsh restrictions on immigrants, have already been written into House Speaker Paul Ryan’s budget, the party’s blueprint for a low-tax, small-government utopia.

Going into the Iowa caucuses, Cruz was cautiously deferential toward Trump. Like a NASCAR driver cheating the wind and riding a leader’s slipstream, he hung behind Trump without challenging him, waiting to make his move.

His moment arrives now, when the race for the Republican nomination turns south, beginning with South Carolina in February, then Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia in March.

George Corley Wallace, Jr. was a genuine son of the Confederacy. Rafael Edward Cruz, a genuine heir to Wallace’s politics of white working-class resentment, is not. The jeans, boots and western-cut shirts are part of a sartorial makeover intended to turn an Ivy League law school graduate into the leader of pitchfork-bearing blue-collar insurgents. Born in Canada, of an American mother and a Cuban immigrant father, his parents’ careers took him to a Houston suburb where he attended a non-denominational Christian elementary school and a Baptist high school. Cruz left Texas after high school and didn’t return until Rick Perry appointed him solicitor general in 2003, when he was working for a small politically connected law firm in Washington. His only other employment in the state was as a partner at a Houston law firm, where he earned $1 million and $1.57 million in the two years prior to his Senate campaign. In 2001, he married Heidi Nelson, who had worked for the George W. Bush campaign in 2000; she later became a Goldman Sachs executive.

Unlike Bush, who built an oil business in Midland then bought into the Texas Rangers, or John Cornyn, who held two statewide elected offices before running for the U.S. Senate, Cruz has no political roots in the state he represents.

As a solicitor general, Cruz had a big job but no name recognition. To voters, he was an unknown, polling from 1 to 3 percent when he filed for the open Senate seat in 2012. The favorite was incumbent Lieutenant Governor David Dewhurst, a telegenic, bilingual, former Air Force officer and CIA agent, who had built a company worth $400 million, and roped calves at rodeos on weekends.

But Dewhurst was damaged goods. As lieutenant governor, presiding over the Senate, he had cut a few deals with Democrats. $16 billion in tax cuts and shrinking state agencies wasn’t enough to satisfy a Republican electorate primed by a Tea Party movement and an animus toward Barack Obama that was inflamed by the rhetoric of elected leaders like former governor Rick Perry and current governor Greg Abbott.

Dewhurst was unaware of his vulnerability. Cruz wasn’t.

The turnout was so low that Cruz was elected to the United States Senate by 4 percent of the state’s eligible voters.

As Cruz tells it he defeated a popular incumbent rich enough to finance his own campaign. Dewhurst spent more than any other candidate in the nation running for statewide office in 2012: $45 million to Cruz’s $15 million.

He had the backing of Rick Perry and the business community, the establishment Republicans who once considered the state their personal fiefdom.

Cruz had the support of today’s Republican Party: policy huckster (and magazine editor) William Kristol, Rick Santorum, Mike Huckabee, Congressman Ron Paul and Senator Rand Paul, and Sarah Palin.

The no-growth, anti-government Club for Growth spent $5 million on ads that defined Dewhurst as an unprincipled centrist who failed to cut taxes enough and accommodated Senate Democrats. FreedomWorks, a Tea Party organization, trained and coordinated Cruz campaign volunteers.

Cruz ran in a pack of primary candidates and forced the frontrunner into a runoff. The Republican presidential race had been decided three months before the July 31 runoff, and runoff elections generate low turnout and attract ideological voters. Cruz won 56.8 percent of the vote. Turnout was so low that he was elected to the United States Senate by 4 percent of the state’s eligible voters.

To put Cruz’s “upset” in perspective, two years after losing to him, Dewhurst was easily turned out of the office he had held for 12 years by a Republican Senator—another right-wing extremist supported by the state’s hardcore Republicans and Christian “values voters.”

In Texas, Cruz bet heavily on the two constituencies that win statewide and national Republican primaries—Tea Party Republicans and evangelicals. He barnstormed the state, speaking to local and regional Tea Party gatherings. His father, an evangelical preacher (albeit of largely fabricated pastoral credentials), preached the Cruz gospel to the Christian community.

Now the senator is doubling down on evangelicals. Since he was elected to the Senate, Cruz or the Rev. Rafael Cruz have appeared at every major regional and national gathering of Christian activists. He is now polling ahead of ordained Baptist minister Mike Huckabee among evangelicals. Focus on the Family founder James Dobson is supporting Cruz, as is Brian Brown of the National Organization for Marriage, Bob Vender Plaats of the Iowa Family Leader, and the Family Research Council’s Tony Perkins.

On the Monday after Christmas, Cruz was the headliner at the Cisco, Texas, ranch of billionaire brothers Dan and Farris Wilks, Christians who’ve gone so far around the bend they’re considered extreme by Texas standards. One of the brothers is the pastor of a local Assembly of Yahweh (7th Day) congregation, a sect that according to Reuters considers being gay a serious crime. Joining the Wilks brothers at the West Texas fly-in were 300 pastors representing the Christian fringe.

By Cruz’s calculation, between mid-February and mid-March evangelical Christians will provide him the votes he needs to secure the Republican nomination. Yet the only general election he has won was in a state that hasn’t elected a Democrat to statewide office since Ann Richards left the governor’s office in 1992.

“The giant difference is that America is not Texas,” pollster Larry Sabato said when handicapping Cruz as a presidential candidate. “That’s his problem.

Lou Dubose is the editor of The Washington Spectator.

Rafael Cruz is truly frightening.