Walt Whitman was right when he wrote that our democracy is an athletic one. Defending our democratic republic requires the stamina of a marathon runner and the versatility of a gymnast.

The events of January 6 alerted Americans to the quirkiness and fragility of our electoral process. Had Vice President Mike Pence failed to certify the electoral college outcome on January 6th, as urged by his boss, the country would have plunged into an arcane contested election procedure prescribed by the 12th Amendment, in which a majority of state congressional delegations in the House of Representatives might have had the final say.

After January 6th the nation has learned that getting from election day to inauguration day in a straight line can be a challenge, especially if the worse angels of our nature prevail in the context of a close election. For too long the balloting on election day was assumed to be dispositive, and the mishmash of laws pertaining to certification (which vary from state to state) were taken for granted. Until, that is, Donald Trump tried to upend the post-election day certification process with fake electors from several states, dozens of frivolous lawsuits and his demand that the Vice President violate his oath of office.

Trump’s largely improvised schemes to hold onto power were ultimately rejected, but his illegal actions opened a window onto additional and equally concerning vulnerabilities in our electoral process that he or other parties similarly antagonistic to democracy might exploit.

The peaceful transition of power requires civic trust and good faith. And to oversee, manage, and certify the final electoral steps mandated by the Constitution, the House cannot proceed without first electing the Speaker. But what if there is a deliberate strategy to block certification of selected congressional seats around the nation, with the aim of skewing the true majority in the House and controlling the vote for the Speakership in January 2025. Or, what if a new Speaker cannot be chosen, or goes rogue? What if due to disarray there is no clear presidential winner by Inauguration Day?

The U.S. is the world’s oldest continuous democracy but idiosyncrasies of the Constitution on which it’s grounded can put the stability of elections at risk. Our founding charter, ingenious and forward-looking in so many respects, contains seeds of its own undoing under certain circumstances.

The problems are not limited to the electoral college, which allows for anti-majoritarian outcomes where the winner of the popular vote does not get to the White House, as happened in the presidential elections of 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016.

No electoral system is perfect. In parliamentary democracies, if an election fails to produce a winner or winning coalition, a caretaker government is left in place, and fresh elections are held to determine a new government according to a timeline. The U.S. has particularly weak or problematic provisions for failed or indeterminate elections for federal office, foremost among these the Presidency. Unlike the Senate and House, there is no provision for a presidential election do-over.

In practice, our Constitution’s electoral process, though antique, has worked as long as people have acted in good faith and in conformity with laws, norms and customs. But what if decency and acceptance of norms is no longer the order of the day? What if a losing candidate refuses to acknowledge defeat? What if third party candidates’ driving purpose is to derail the general election process so they can bargain on the House floor over the selection of a President, and for a price? What if people are willing to act in bad faith and game the system?

The venerable Constitution is often praised for interpretive “elasticity” and “durability,” but key election process clauses of the founding document contain a combination of ambiguity, rigidity and silence that can be a recipe for disaster when left to unscrupulous actors. Close elections pose particularly high risks for mischief. As Robert Cindrich, the retired Federal District Judge from Western Pennsylvania, has observed, the Constitution is ultimately a “gentleman’s agreement” among all interested parties to behave properly.

Potential pathways for those of bad faith to grab power through a constitutional coup were revealed on January 6th and now are proliferating. Warning lights for 2024 are flashing. As former Congresswoman Liz Cheney has cautioned, the constitutional checks and balances may not be sufficient to prevent the potential for chaos ahead.

What could go wrong?

The American public approaches the election of 2024 more ideologically divided and distrustful of the democratic process since the pre-Civil war election of 1860. Since January 6th, the Trump camp has relentlessly propagated “Big Lie” allegations of a stolen election in 2020 and a rigged election to come in 2024. Trump has ominously declared there will be no need to vote but rather urged his supporters “to stop the steal” at the polls. The leading Republican candidate’s rhetoric makes clear that he will never accept any election result but his return to the White House.

Here are three examples of what could transpire after the ballots have been cast on November 5, based on extrapolation from precedents, circulating threats and unfolding strategies.

1. Hijack the House

Strategies for gaming the congressional certification process for House members at the federal and state levels.

Many civic leaders are rightly focused on the vulnerabilities of the state certification process for Presidential electors, where efforts to overturn or nullify a state’s Presidential ballot results have been normalized. But they are not yet focused on the equal threat of the weaponization of the House and State certification process, with their implications for the seating of the House of Representatives, election of a new Speaker and ultimately the confirmation of the new President.

a) Gaming the House Certification Process

Every two years, voters elect an entirely new House to be seated on January 3, in accordance with the 20th Amendment.

While individual states administer elections and certify Congressional elections, final certification of all House seats is ultimately up to the House under Article 1, section 5 of the U.S. Constitution, which states simply “Each House shall be the Judge of the Elections, Returns and Qualifications of its own Members.”

The Federal Contested Elections Act of 1969 clarified procedures for a Congressional challenger to submit within 30 days of the election a notice of contest to the House Committee on Administration. Under the Act, the committee may dismiss or investigate the challenge, order a recount, or call for a new election, and it is supposed to make a recommendation for vote by simple majority in the full House.

These rules for the internal House adjudication process are less strictly legal than they are parliamentary and political. Generally, their disposition cannot be appealed in Federal courts. Indeed, according to what is known as “parliamentary law” or customary House practice, the sitting House majority is free to change or waive previously adopted rules, even those imposed by statute such as the Federal Contested Elections Act, provided that it does not “ignore constitutional restraints or violate fundamental rights.” In short, within certain limits, the majority in the House can make up the rules as they go without fear of court oversight.

In 1984, an exceedingly tight Congressional election in Indiana’s 8th district led to a brutal six-month dispute with multiple state recounts and a Congressionally-led audit. At the insistence of the Democratic House majority, who believed it had principled concerns about the integrity of the election, the 8th district’s seat remained vacant until May 1985, when a controversial split decision of a three-member committee chaired by Congressman Leon Panetta declared the Democratic candidate had won by a margin of four votes. In the eyes of the enraged Republican minority, the Democrats broke all norms and used its majority power to refuse to seat a Republican candidate duly certified by the state. President Reagan later remarked that Democrats “threw your votes out the window, and in a naked display of power politics, they simply handed your district to their own man. It was an act of unprecedented arrogance.”

Congressman Dick Cheney, too, warned the House Democrats that refusing to seat a state-certified winner and instead seating their own candidate through a partisan-controlled recount procedure violated accepted norms and comity. The bitterness of this battle led to the first major walkout in 95 years of a party’s entire delegation – the GOP members wore “Stop the Steal” pins as they exited. It could be argued the memory of that Republican loss helped prepare the Republicans for the type of power play required to prevail in the 2000 Florida Bush v. Gore recount battle, which determined the election of President Bush.

At the time of the Indiana dispute, Democratic Congressman Jim Wright (who later became Speaker) maintained that the House leadership conducted the recount and certification process in a non-partisan, untainted manner but he also noted that, in reality, the House majority has the “raw power” to select whomever they want to fill a Congressional seat, regardless of state certifications and vote counts.

The Indiana election dispute underscored that while the burden of proof should lie with the challenger, the authority to determine sufficiency of evidence lies not with independent courts but solely with the House Committee, leaving the door wide open to partisan power plays. The legacy of the 1984 disagreement poses a danger to the nation in the 2024 election cycle.

b) Gaming the State Certification Process

In another salient disputed election case, the 2018 election for North Carolina’s 9th district was clouded by allegations of significant fraud on the Republican side. The state did not certify the results. The seat was left vacant when the House convened on January 3 and remained empty for almost a year. The North Carolina state election board called a new election for September 2019, which the Republican contender won.

But what if in 2024 a governor, secretary of state or other authorized state-level actor goes rogue and attempts in a radical, unpreceded, and fraudulent manner to withhold a state’s election certification for one or more selected seats, regardless of the facts? What if Texas might fail to certify one or more of its many Democratic seats. This is hardly fantastical. Against all norms, in 2020 Texas state authorities attempted to challenge in court the electoral vote counts in other states. That challenge rightly failed but who knows to what lengths Texas, or any like-minded state might go in 2024. And what if New York feared such an action and preemptively moved to do the same?

The upshot of these precedents is that there is potential for the strategic misuse of challenges – both from the state level and within the House itself – to shape or otherwise impede the seating of a new House and thus to hijack the majority position and the Speakership. If the situation devolves into political chaos, it could also delay the selection of a new Speaker.

To be clear, these two disputed House cases were accidental in their origins, the scale small, and the tactics used opportunistically. But what if this type of certification delay at state or House levels or both played out on a larger and coordinated scale? And if the task of establishing a majority in the new House comes down to a handful of seats, the risk of strategic disruption increases.

Simply put, in such House seat dispute scenarios a rogue Speaker of the current 118th Congress could, with support of a cohesive majority, manipulate, strong-arm, or otherwise abuse House rules and procedures to guarantee (and control) a majority of the members for the 119th Congress in January 2025.

Good faith can no longer be assumed. In 2020, current Speaker Mike Johnson, in a purely partisan act, organized 138 Republican House members who were in the minority to refuse to certify the election of President Biden, despite state certifications of the outcome of the vote and the almost universal rulings from state and federal courts that it was an honest election. Indeed, in multiple cases where Republican state legislatures refused to accept a Biden win and conducted recounts in their respective states, the results confirmed the original tally. Still, Johnson cried foul. Imagine if Johnson had been speaker in 2020.

As Berkeley constitutional law scholar Erwin Chemerinsky has warned: “Now that Johnson is House speaker, there is no telling what he will do to undermine the election should Trump become the GOP nominee. Given his extreme loyalty to Trump and his efforts to spread outrageous lies and to nullify the 2020 election, the peril for the democratic process is great.”

Many people have trouble imagining that Congressional leaders would refuse to certify the results of a Presidential election solely because they don’t like the outcome. It is worth noting that in remarks as recently as this past Sunday, Elise Stefanik, the fourth-ranking Republican in the House, publicly refused to commit to certify the results of the 2024 Presidential contest.

Next to the election of the president nothing is more important than the election of the new Speaker of the House. The party controlling the Speakership has the potential power to reverse the results of the Presidential election and deliver the White House to itself under the untested presidential succession mechanisms pursuant to the 20th Amendment and the Succession Act of 1947.

An added complicating variable for the House equation in 2024 is the third-party spoiler strategy of Bobby Kennedy Jr. and the No-Labels campaign, whose aim is to prevent the two major party presidential candidates from achieving the needed 270 electoral votes on January 6th. They would thus force a contingent election in the House where their purpose is to play the role of kingmakers at the expense of the voice and vote of the American people.

2. Short-Circuit the Electoral College

Overt corruption of the electoral college process is by now a more familiar pathway to perdition because something like it occurred in the run-up to January 6. Trump’s efforts to use parallel slates of electors from a handful of states to confuse the certification process was a form of constitutional coup that Vice President Pence heroically refused to support, even as violent mob insurrection at the U.S. Capitol was unfolding.

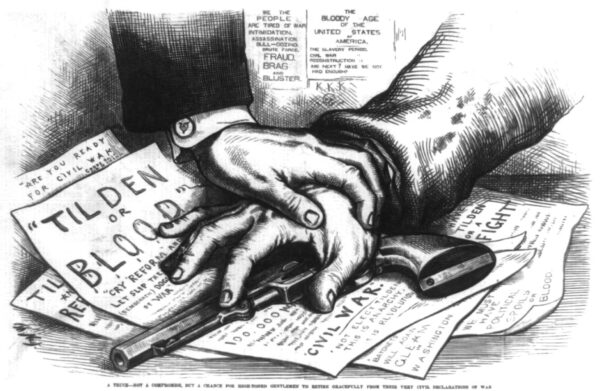

Alarmed by these events, in 2022 Congress amended the Electoral Count Act (ECA) to clarify the process of electoral college certification and to patch holes in that 1887 statute, which itself was a legislative response to the 1876-77 Tilden-Hayes presidential election debacle. The original ECA had long been criticized by election law experts for the ambiguities and loopholes that helped set the stage for January 6th.

The Compromise of 1877: A political cartoon by Thomas Nast that appeared in the February 17, 1877 issue of the American political magazine Harper’s Weekly. The cartoon is in response to the compromise of 1877. The caption says “A truce—not a compromise, but a chance for high-toned gentlemen to retire gracefully from their very civil declarations of war.”

The bi-partisan Electoral Count Reform Act (ECRA) has clearly tipped authority to governors (not legislatures) to certify electoral slates at the state level, raised the threshold for challenges in the Joint Session of Congress under the 12th Amendment, expressly limited the time for floor debate, and clarified the role of the President of the Senate (the Vice President) in counting the electoral votes as solely ministerial and thus without any discretion to invalidate electors or choose between dueling slates. The ECRA was a smart legislative attempt to iron out wrinkles in the antiquated electoral process and avert a replay of the 2020 drama. Eliminating the absurd notion that a single individual such as the Vice President could or should decide a national election outcome seems an obvious step for any modern democracy.

Nevertheless, ECRA remains vulnerable to potentially serious challenges. For example, a party with standing (such as one of the presidential candidates) could challenge aspects of ECRA relating to the states as unconstitutional on the theory that a statute cannot amend the Constitution’s terse provisions for the election process which favors state legislatures. In this context, the threat of the so-called “independent state legislature (ISL) theory,” a dubious legal doctrine that suggests state assemblies have the right to override the popular vote, has received considerable attention.

In its much-anticipated 2023 decision in Moore v. Harper, a North Carolina gerrymandering case about court review of state legislative authority over rules affecting federal elections, the Supreme Court showed no appetite for applying the pre-Civil War states’ rights philosophy embedded in the ILS to contemporary elections. This was a good sign. That said, a Court majority that has the chutzpah to reverse longstanding precedents such as Roe and Bakke – and to trim rather than enhance the desperately needed protections of the Voting Rights Act – has also shown itself to be capable of paradigm shifts against popular expectations.

But there is another potential hurdle for the procedural improvements of the ECRA to be effective. Like the Senate, the House is a self-governing body. But unlike the Senate, the House is not a continuous legislative body and therefore each new session must adopt its own parliamentary rules. The House of Representatives is like a relay race where each time the baton is passed it goes to an entirely new runner.

Thus, as a technical matter, the key provisions of ECRA are effective only if affirmatively adopted by the newly constituted House. Again, keep in mind that Speaker Johnson organized 138 Republicans to vote in opposition to the ECRA. Furthermore, because it is a political question involving the internal operations of the legislative branch, the Supreme Court would be unlikely to impose on Congress the strictures of ECRA relating to House rules.

Indeed, if a Republican majority under the current aggressive and unilateralist style of leadership — which has been willing to oust its own Speaker and threaten government shutdowns and U.S. debt default—is re-established after January 3rd, 2025, it is doubtful whether the new 119th House would adopt the ECRA in its rules package. Failure to adopt that set of rules would increase the risk of a chaotic electoral certification process with an uncertain outcome, including immediate resort to a 12th Amendment contingent contest for President in the House and for Vice President in the Senate, also determined by state delegations.

In other words, we could be plunged backwards to a pre-ECRA world which was ambiguous on key procedural points such as what to do with rival electoral slates, or even to a no-ECA world, with only the imprecise words of 12th Amendment to guide the selection process of a President and Vice President.

Furthermore, another risky quirk of the Constitutional electoral timeline is that, unlike January 3 which is the fixed end of the 118th House term, and January 20 which is the fixed end of the presidential term, January 6 (the date of electoral vote certification) is a changeable date. Under the 20th Amendment, Congress has authority to shift that date; while this would require concurrence of the House and Senate and would be subject to presidential veto, in theory at least the date could change. This flexibility could be helpful in the interests of the timely qualifying of a president, should there be a problem convening on January 6.

However, imagine there is a problem seating the new House owing to failed or competing certifications. Absent such a date change, a failure to certify the electoral college result on January 6 as prescribed would implicate the 12th Amendment. But again, what if there’s not yet a Speaker to convene the House and preside over the contested election process? (The role could possibly devolve to the Senate president pro tempore, the most senior Senator in the majority party caucus) In 2023 it took 15 votes for Kevin McCarthy to be elected Speaker. Such delays could intentionally or unintentionally spill over the January 20th deadline, which brings us to the next form of potential constitutional crisis, and perhaps the ultimate nightmare scenario.

3. Filibuster the Presidential Inauguration

According to the 20th Amendment, January 20 after an election is a rigid date for the end of the outgoing president’s term. This firm deadline is a useful protection against a president who unlawfully tries to extend his term, but it creates a possible conundrum. What if, due to delays from one of the conflictual scenarios just described, there is no qualified president by high noon on that date?

Without a qualified President or Vice President by January 20, the country would be in the uncharted waters of applying the Presidential Succession Act of 1947 as amended.

The Succession Act provides for an “Acting President” – language borrowed from the 25th Amendment in the case of a president’s physical incapacity — until a new President qualifies, which is exceedingly vague and potentially unsatisfactory for democratic legitimacy. For example, would the nation accept an unelected “Acting President” for four years until the next regular election?

As Jean Parvin Bordewich & Roy E. Brownell II, former senior staffers to Senate leaders Charles Schumer and Mitch McConnell respectively, point out, the Succession Act has significant gaps and shortcomings, These include the fact that legislators such as the House Speaker and Senate president pro tempore could succeed as “Acting President,” raising serious questions of political legitimacy. After all, why should legislators (who could be from either party) be assigned to the highest executive office without an election? Whether appointed Cabinet secretaries from the President’s own party are any more suitable as acting successors for prolonged periods without an election is also an open question. Fundamentally, there is a difference between mid-term succession in cases of death or incapacity (which the 25th Amendment addresses) and succession in the case of a failed presidential election.

Legal formalists may insist that all likely contingencies have been anticipated and there is no need for concern. Yet one wonders whether the Succession Act would in fact be implemented or accepted in such a controversial situation as a failed election. Might it be viewed by voters as too flimsy a process to handle a failed presidential election? Indeed, why should a strategy based on known election manipulation be allowed to determine succession to the presidency, even if only acting, when we know that free and fair elections must be the touchstones of our democracy?

It is noteworthy that in the presidential election crisis of 1876-77, even the 12th Amendment process was circumvented and instead Congress (then unconstrained by a Succession Act of its own making) opted for a special fifteen-member commission of eminent persons to broker a political settlement between the Tilden and Hayes camps. Tellingly, as legal scholars David Fontana and Bruce Ackerman have explained, this was done precisely to avoid allowing a highly partisan and untrustworthy Senate pro tem figure to preside over the contingent election process in lieu of the absent Vice President (who was deceased).

The result – awarding the presidency to the loser of the popular vote – may have avoided an even deeper national crisis, but it came at the devastating cost of undoing Reconstruction policies in the South. Could we be headed for some kind of brokered presidency in 2025, as hoped for by third-party nihilists and spoilers such as Bobby Kennedy Jr. and No-Labels? Would this further polarize an already dangerously divided nation?

What can be done?

Each of these “raw power” scenarios would require a big dose of bad faith and sinister conspiracy to succeed. Each would entail an aggressive and opportunistic misuse of Constitutional ambiguity and the laws of the land against the founding democratic spirit and principles of popular sovereignty and limited government.

Yet we already know too much not to engage in preemptive strategies to neutralize any fresh attempt at a constitutional coup. We can have no illusion in 2024 about the threat level – unscrupulous actors on the current political stage have been looking for constitutional loopholes and avenues to take power if it cannot be done by fair means. It is noteworthy that the former president has declined to sign the Illinois pledge not to advocate for the overthrow the U.S. government – at least he is not a hypocrite.

Preparedness is essential. Its purpose is not scaremongering; rather, it is vital to the anticipatory defense of our constitutional democracy.

As citizens in a democracy, we are not mere bystanders or spectators. We must strive to preempt those who would subvert our electoral process. No invisible hand will save us. To survive, we must act.

Here’s how: Apart from eligible voters casting their votes, there are three principal domains of citizens’ defense against a constitutional coup.

First Line of Defense: The Courts

While there may be no sure-fire legal remedy for the “raw power” tactics Representative Wright referred to, the courts matter.

Courts performed well in 2020, with independent judges (many of them Trump appointees) striking down scores of trivial and unsupported election challenges. They must be ready again.

Members of the constitutional and election law bars committed to upholding best practices – including all the lawyers and election experts who have been engaged in litigation at state and Federal levels in the aftermath of the 2020 election—must be prepared to defend the ECRA and to decisively defeat the states’ rights notion that state legislatures have authority to veto the popular vote, among many other knotty legal issues.

In addition, the prosecution of the various January 6 conspirators, including at the state level, as well as the disbarment of lawyers who aided and abetted the various election interference plots, has had an important ongoing deterrent effect on others who would contemplate such tactics in the future. The lesson is that individual wrongdoers are being, and should be, held to account for complicity in stoking election and post-election chaos, even though Trump is still encouraging bad actors by signaling he will pardon such past and future behavior if elected.

True, time can be an issue when it comes to the legal remedy. Justice delayed is justice denied. The normal Federal prosecution and appeals process can be drawn out. It has taken more than three years to respond to the “high crimes” of January 6 through the courts. We still have no definitive resolution with respect to the multiple Federal and state charges against Trump. Yet any of the nightmare scenarios described above will involve real-time court challenges during the pressure-cooker transition period.

The Supreme Court is unlikely to preemptively fix any of the major constitutional election conundrums—because the issues are not ripe or they involve political questions. Nevertheless, the ultimate normative check on an attempted constitutional coup could reside with the high court if it chooses to intervene amidst an election crisis. Such interventions can be a two-edged sword, as we learned with the Court’s controversial ruling to cut off the ongoing Florida recount in Bush v. Gore.

Twenty years ago, in the wake of Bush v. Gore, legal scholar Mark Tushnet argued there have been critical moments in our country’s history when the political order is tested by “constitutional hardball” – when aggressive tactics are used to advance partisan goals.

Such tactics risk pitting the letter of the constitution against its spirit. On a number of key occasions, such as Marbury v. Madison (1803), a case establishing the authority for judicial review of laws and acts by other branches, the Supreme Court have resolved such conflicts by charting a principled way forward in accord with a compelling reading of the Constitution. But “constitutional hardball” by definition can take things to the brink of disaster because, as Tushnet describes, the political actors, whether executive or legislative, are “playing for keeps” about foundational issues with high stakes for their policy agendas.

Indeed, the arena of legal hardball is where sharply competing political visions of the Constitution’s meaning and interpretation – for example, the “original intent” versus “living document” or the states’ rights vs. New Deal government schools of thinking– duke it out on first order questions. This is the contentious crossroads of the rule of law (which Justice Scalia defined as “the law of rules”) and political philosophy (the realm of values). In regular times, the law has much room for spirited and even acrimonious political give and take, but there are boundary lines that test the integrity of the entire democratic Republic. Constitutional hardball takes us to edges of those frontiers, for better or worse. Political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt have warned that constitutional hardball can open the road for devolution from democracy into authoritarianism,

In this context, a Supreme Court majority willing to step in and “do the right thing” could save the Republic. But constitutional hardball is inherently high risk and can be played by both sides who do not agree on what “the right thing” is.

For example, there is no guarantee that under pressure of a hot political crisis the current Supreme Court majority would uphold the application of equal protection embodied in a long line of landmark voting rights case such as Baker v Carr (1962), Gray v Sanders (1963), Reynolds v Sims (1964), and Wesberry v Sanders (1964). The one person, one vote principle is the basis for popular sovereignty but (like gender equality or the right to privacy) the individual right to vote is not found in so many words in the Constitution.

One 2024 version of constitutional hardball is already starting to play out. The “insurrectionist” ballot cases under the 14th Amendment Section 3, a post-Civil War clause which prohibits people who “engaged in insurrection or rebellion” against the United States from serving in federal office, could plunge us into a constitutional crisis involving the Supreme Court even before the November election. The Supreme Court has taken up the Colorado ballot exclusion case and its ruling will be highly consequential either way. The Democrats’ preemptive invocation of “14:3” to ban Trump from ballots is itself a form of constitutional hardball and, whether or not lustration of the former president succeeds on the merits, raises the risk of tit-for-tat escalation.

Second Line of Defense: Parliamentary Gymnastics and State-level Deterrence

Congressional and state leaderships have key roles to play in countering the threats to an orderly election and peaceful transition.

The Speaker, if principled, may have the ability to prevent a constitutional coup through procedural discipline and if necessary stronger parliamentary tactics, another form of “constitutional hardball.” For example, in the 2020 election House Speaker Nancy Pelosi had hardball tools of parliamentary maneuver at her disposal, including quorum rules, if the 12th Amendment contingent election power play was attempted. But again, all depends on the character of whoever occupies the Speakership in January 2025.

In addition, at the state level, if bad actors attempt to “hijack the House” with multiple coordinated frivolous challenges, principled government officials in other states could threaten to counter such a strategy by withholding their own election certification of House Members. This type of deterrent threat should be used only as a last resort and be subject to a strict doctrine of “no first use.” With an incipient House crisis, “mutual assured destruction” would take constitutional hardball to a new level but could also avert a power grab.

Third Line of Defense: The Marathon Work of Rallying Bipartisan Voices and Building a Citizens’ Firewall for Democracy

Bipartisan former and current members of Congress, governors and other leaders must be prepared to engage prophylactically in sustained vocal advocacy to protect the democratic principles of the Constitution. Appeal to common sense decency and fair play will be essential to summon the better angels of our nature – this has been America’s saving grace across generations. Denying a rogue Speaker a united House majority is one of the most powerful weapons. This principled advocacy must be done in advance of November as a clear warning to those who might be trying to hijack the House or otherwise hobble the transition and seize power by skullduggery. Members of the House should be strongly encouraged to cross party lines as needed to prevent a majority under a rogue Speaker.

Finally, broad public consciousness-raising through media and civic engagement remains imperative. We must continue to stimulate bipartisan civic discussion at the precinct level of town halls, fire houses and civic centers to preempt mischief and to rebuild trust wherever possible. The grassroots activism of concerned citizens is always the strongest antidote to potential abuses of power. Neighborhood stalwarts, pillars of the community and civic-minded influencers should speak up across the country. As former Pennsylvania Republican Governor Corbett has put it, “we need hyper-localized dialogues about democracy.” De Tocqueville could not have said it better.

As we head into the primary season, the message to voters and responsible officials alike is simple: We Americans must remind ourselves that we know how to hold honest elections, how to count votes and how to respect outcomes when all the votes are tallied. Fortunately, since 2020 many diverse non-partisan civil society organizations have sprouted to spread exactly this message across the land.

We must continue to build the barricades of public opinion against each of the foreseeable dark scenarios – hijacking the House, short-circuiting the electoral college, and filibustering inauguration day.

Fundamentally, the citizens’ mandate is for We The People to “just say no” to rampant election denial and to incipient schemes to undermine the 2024 election. Media pundits, opinion leaders, elected officials, law enforcement, and the public at large must all speak up if there is the slightest sign of intent to manipulate the post-election day process and overrule popular sovereignty.

Conclusion

The dark scenarios we have outlined are hopefully remote, but given what happened during the run-up to January 6, and on the day itself, the deep societal polarization, chaos in Congress, and the rise of extremist rhetoric, we must not let a failure of imagination impede our preparedness. Constitutional hardball must not be allowed to devolve into just plain hardball, or we will lose our Republic. In truth, we are already in the fight.

Mark Medish, a lawyer, served as Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director of the National Security Council as well as Deputy Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Treasury in the Clinton Administration. Joel McCleary served as Deputy Assistant to the President in the Carter Administration.

Amazing piece of legal and Constitutional analysis. Extremely lucid explanations of complex hypothetical election scenarios. Well done Medish and McCleary! There is, as you show, ample room for bad faith to upend our democracy. We are left trembling.

Excellent summary of many horribles, many of which could be eliminated by a functioning national legislature that removed the Electoral College from the process of selecting the President and moved the United States in the direction of popular democracy.

This is a good start. Let’s add this to the dozens and dozens of essays, articles, entire issues (See Atlantic Dec 5 2023) and podcasts warning everyone of the risks associated with a return to power of MAGA.

What is the actual plan of action should this actually occur?

https://medium.com/@jylterps/trump-resistance-plan-trp-2-0-a-call-to-action-to-prepare-for-the-worst-case-scenarios-de89efabb8e5

While most of us are by now aware of potential threats to the next presidential election in the form of disputes about mail in voting, vote counting apparatus and potentially violent election interference, Messrs. Medish and McCleary focus on arcane legislative procedures that could be potentially much more concerning and more difficult to remedy. Only someone with an intimate knowledge of House rules and procedures could have produced this valuable analysis.

With the MAGA-Johnson crowd, all of these are real possibilities. We need to be ready for them. But the real imperative is to win elections by margins that make the results undeniable.

An excellent article by people who obviously understand legislative procedure. There is a well-established ( at least at the state level) principle that one legislature cannot control the procedure used by a subsequent legislature in exercising its constitutional duties . Statutes that attempt to do so are “ministerial” but not “mandatory”. Accordingly the ECRA is useful only to the extent the 2025 Congress accepts it as valid. I’m glad to see that the authors understand that. The five member majority in Bush v. Gore did not appear to have a similar understanding of the ECA, though perhaps it was just one of many legal principles that court chose to ignore.

Really very interest piece, thank you from New Zealand via Robert Reich on Substack.

Not sure that it is accurate to assert that Donald Trump is not a hypocrite; the example used here possibly not being representative? “It is noteworthy that the former president has declined to sign the Illinois pledge not to advocate for the overthrow the U.S. government – at least he is not a hypocrite.”

All the best.