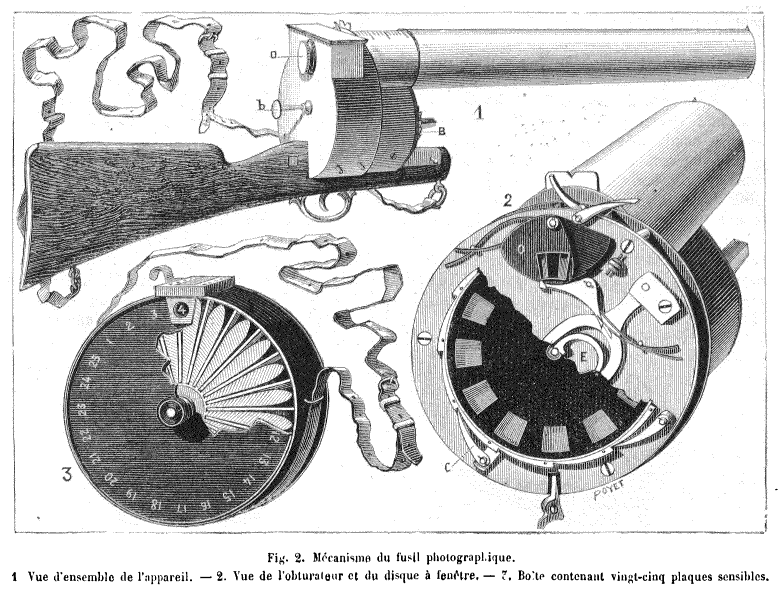

Marey’s “fusile photographique”

In the late fifties, Diane Arbus spent summers skulking around Coney Island movie theatres and taking pictures of projections. In her ensuing image series, film noir vamps growled and sneered at her with the same ferocity as her subjects often did. “Onscreen woman with hoop earrings and a gun” (1958), on view through July 31 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “Crime Stories: Photography and Foul Play,” depicts a close-up of an unknown star, from an unknown film. It enlists the pictured screen as a divider between two shifty-eyed shooters standing face-to-face in the dark: the criminal raising her gun, the photographer pointing her camera.

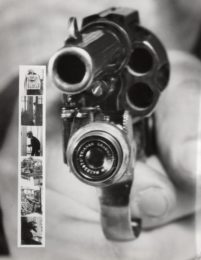

The connection between shooting film and shooting bullets is not unique to Arbus’s image: it’s part of the history of image capture itself. In 1882, Étienne-Jules Marey invented the world’s first portable motion picture camera, a rifle-shaped “fusil photographique,” or photography gun, that he used to take pictures of birds at a speed of 1/720th of a second in order to animate their flight. A 1934 issue of Popular Science advertises a camera attachment that could be fastened to a working pistol in order to “trap crooks,” while a Colt .38 “revolver camera” was designed with the perverse intention of capturing criminals’ looks of surprise at the moment when the trigger was pulled.

Colt .38 “revolver camera”

Though revolver cameras and their antecedents are absent from “Crime Stories,” many of the photographs featured in the exhibit qualify as their own form of “foul play.” A 1928 image of Queens housewife Ruth Snyder—sentenced to the electric chair at Sing Sing for the murder of her husband—was taken mid-execution by New York Daily News journalist Tom Howard with a miniature camera that he had strapped surreptitiously to his ankle. The image of Snyder with electricity coursing through her veins sold record copies of the Daily News and even caught the eye of Billy Wilder, who used her story as the basis for Double Indemnity (1944), starring Barbara Stanwyck. (The Met’s newspaper clipping is from Walker Evans’s private album.)

Though the identities of the tabloid junkies who bought copies of the Daily News are largely lost to history, we museumgoers make good stand-ins for the everyday rubberneckers who first fueled this media apparatus, and gave it teeth. Today’s images of the insane, the dead, and the dying are no longer wreathed in sensational 1930s era headlines (above Snyder’s image, the word “DEAD!” in 97-point font, is all that is printed), but past tastes for the perverse will ring true to those of us standing shoulder-to-shoulder at the Met to get a look at a photo of a 15-year-old murderer, or Weegee’s seductively titled, “Human Head Cake Box Murder.”

As the exhibition timeline originates in the late 1800s and tapers off in the 1970s—just before the onset of the 24-hour news cycle—“Crime Stories” does not engage with the image capture methods of our modern carceral state, nor does it invoke today’s mass consumption of true crime. More often, the show’s entanglement of crime and cinema mediates our approach to past acts of violence by situating the events among fiction, glamour, and nostalgia. Title cards remark on the resemblance of 1940s autopsy photographs to Hitchcock shots and scenes from Taxi Driver, while collections of old-timey mug shots evoke the sullen beauty of rising stars during Hollywood screen tests.

Perhaps because of its interest in crime as a catapult to stardom, “Crime Stories” is less effective in critiquing systems of power than it is in establishing how history’s most powerful rose to prominence. “Godfrey,” taken in 1971, is captioned to acknowledge “the advent of cell-phone cameras and the resulting revelations of police misconduct and brutality” as they destabilized “the once infallible word of the authorities.” Rather than highlighting gaps in the photographic archive, words like these perpetuate the erasure of history. We know that long before cell-phone cameras—and at least a decade before 1971—members of the Black Power movement and the Civil Rights movement were organizing radically and visibly against a reality of police brutality that was, even then, far from a “revelation” to the general public.

The execution of Ruth Snyder.

A section dedicated to Paris policeman Alphonse Bertillon situates his invention of the mug shot as an expression of the same obsessive fandom that later fueled tabloid culture. For no pay, Bertillon spent free hours examining inmates at La Santé and collecting photographs and descriptions of criminals in order to substantiate popular 19th-century notions of physiognomy. The fetishistic undercurrent to his albums illustrates how, in policing his subjects, Bertillon also couldn’t help but admire them—in their meticulous attention to attributes such as the length of a middle finger or the “depth” of a brow, the photos and text are less convincing as police data than as a sort of anthropometrics of criminal allure. There’s evidence that Bertillon once went so far as to intermingle his position of policeman/fan with his role of father: an affectionate mug shot of his not-yet-two-year-old son, Francois, shows his child under arrest for “nibbling pears from a basket.”

The messy intimacy of Bertillon’s engagement with his subjects—his conflation of the surveilling, erotic, and even tender gaze—may ultimately help museumgoers make sense of likewise messy gazes that “Crime Stories” prompts its viewers to assume. When visiting the exhibit, I found myself alternately indicting and admiring the figures portrayed; performing my shock or ironic detachment toward accounts of grotesque acts; taking pleasure in images of violence, and finding guilt in that same pleasure. If the camera was first conceived as a harmless hunting device designed to still a dove’s flight on film, then “Crime Stories” illustrates the way in which our image appetites have only gotten stranger and sicker over time. It does not rigorously account for the predilections of the masses, nor does it instruct us in how to recognize or correct for them. At best, “Crime Stories” may leave you more or less as it did me: interested, shifty, wrestling conflicting impulses in the dark.

Isabel Ortiz is a writer living in Queens.

0 Comments