Will Benjamin Netanyahu go down in history as the Israeli prime minister who cried wolf once too often regarding Iran’s nuclear-technology program? It looks that way. Back in the mid-1980s, when I started studying and writing about nuclear proliferation issues in the Middle East, the anxious estimates of most Israeli and pro-Israeli “experts” concluded that Iran was “around two to three years—absolute maximum five years” away from producing a nuclear weapon.

That was 30 years ago. In the years since, essentially that same estimate has been routinely bandied about. But very few people writing in, or quoted in, the American mainstream media ever tried seriously to examine two key aspects of that warning: (1) Was Tehran indeed seeking to use its quite legal nuclear-technology program to prepare the production of nuclear weapons; or (2) Why did all the “experts” producing those doomsday warnings routinely call it wrong—and why did no one ever call them out on their error?

For 30 years, the American mainstream media have kept alive the threat that Iran might any day “break-out” from the terms and restrictions of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. The Vienna Agreement breathes new life into the NPT and brings the United States more firmly back into the “community of nations.”

So for all these past 30 years, the American mainstream media have kept alive the threat that Iran might any day “break-out” from the terms and restrictions of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT)—to which Iran but notably not Israel is a signatory. And the vividness of this threat of break-out kept the hostility of the U.S. political elite towards the Islamic Republic of Iran at a high level long after the anger engendered by the 1979-1980 Tehran hostage crisis had started to abate. That hostility was evident in the ever tighter and tighter sanctions Congress imposed on Iran. Meanwhile, for successive leaders (of all parties) in Israel, continuing to hype the “threat” that an imminently nuclear-armed Iran would pose to Israel served to distract U.S. presidents from their continued and unwelcome (to Israelis) insistence on pursuing a Palestinian-Israel peace agreement.

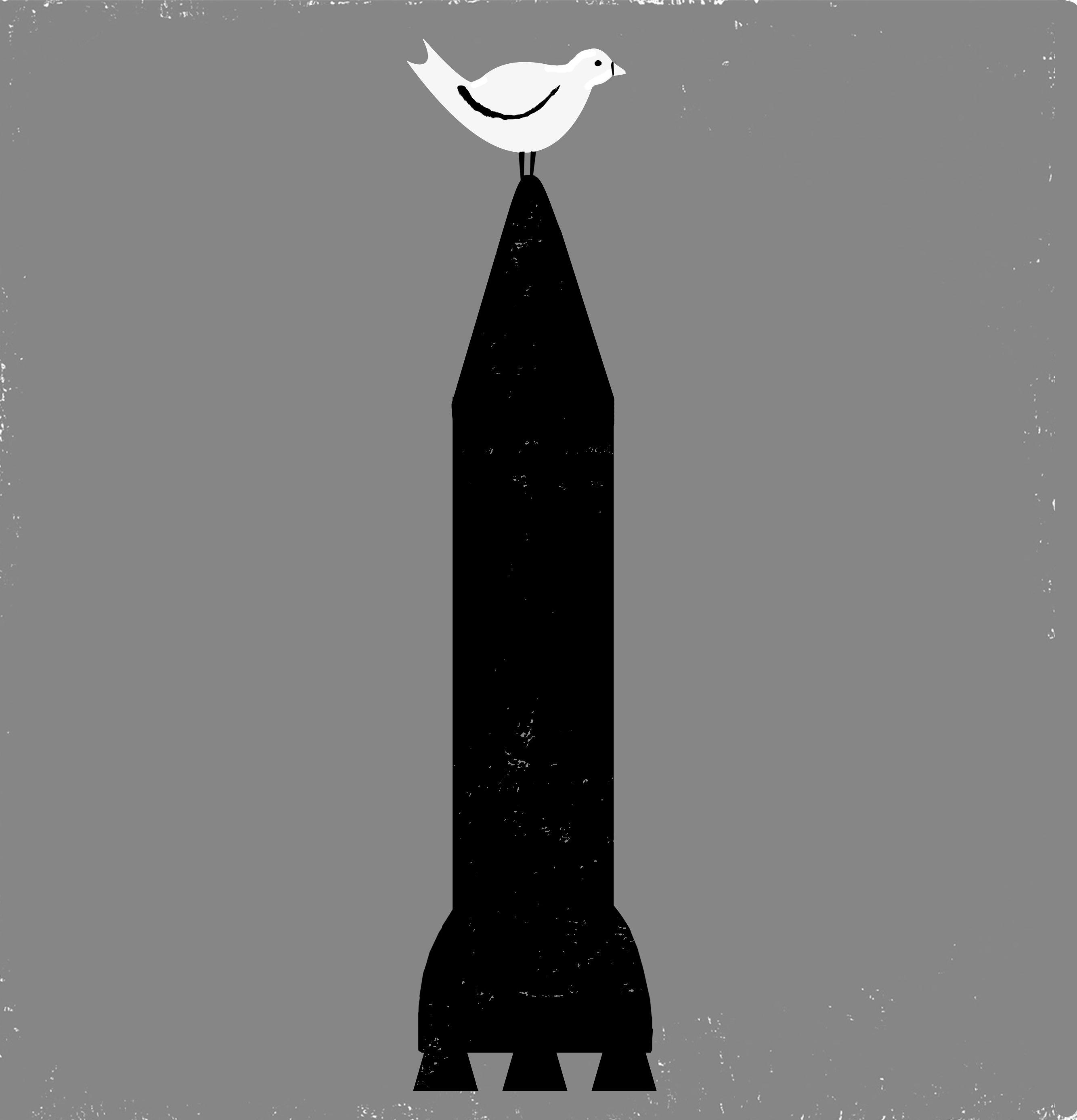

After Netanyahu returned to the premiership in 2009, he took the hyping of the Iranian nuclear “threat” to new levels. It was not just the clunky infographic that he took to the United Nations (and which provided an instantly recognizable cover for Gareth Porter’s detailed takedown of the evidence on which the “threat” was based, Manufactured Crisis: The Untold Story of the Iran Nuclear Scare, published by Just World Books, the publishing company I own). It was not even Netanyahu’s continued push to ramp up anti-Iran pressure within the U.S. Congress to ever higher, and more partisan (rabidly anti-Obama), levels. Most probably, what was even more troubling for President Obama and his advisors were the increasingly bellicose threats Netanyahu started making, to the effect that if the United States would not take military action against Iran, then Israel might have to, itself. With scores of thousands of U.S. troops vulnerably stationed in and along the southern shore of the Persian Gulf, and with no plausible way at all for the U.S. to dissociate itself from Israel’s actions against Iran, any such attack would provoke an almost immediate Iranian counter-attack against U.S. forces and thus catapult the United States into a massive and messy war against Iran from which it would be very, very hard to discern any even remotely acceptable exit.

When Obama and his cabinet members say, as they repeatedly have since the signing of the July 14 nuclear agreement with Iran, that “the only alternative to this agreement is war,” this is probably the unwelcome war scenario they have in mind—though it would be impolitic for administration officials to spell out to an American public that it was mainly Netanyahu’s shrill war-blackmail that prodded them into nailing down the negotiated agreement with Tehran.

If Obama Prevails

It now seems likely that Obama will be able to override any veto the opponents of the Vienna Agreement will throw his way, and implementation of the agreement will proceed. This will have large-scale consequences on the politics of the Middle East—but probably even greater ones on the global balance of power.

At the regional level, the beginning of a working relationship with Iran will enable the United States and other “Western” nations to start potentially productive discussions with Tehran on how to approach common problems in the region—primarily the emergence and continued growth of the Islamic State (IS).

In Iraq, Iran, and the U.S. are already engaged in a delicate do-si-do. Both technically support the Baghdad government; but both are aiding different factions of the anti-IS forces in different parts of the country, albeit with frequent overlap. In Syria, the situation is far more complex. Iran gives large support to the Assad government, while the Obama administration still seems committed to the push it has pursued since Spring 2011 for complete regime change in Damascus as a precondition for any later negotiation on Syrian political reform.

Might the partial improvement of relations between Washington and Tehran allow both sides to find some political accommodation regarding Syria? I certainly hope so. However, in all matters involving IS, Washington also has to deal with the uncomfortable fact that key U.S.-allied governments like those in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and even NATO member Turkey have provided support to IS—ranging from “turning a blind eye” to its activities, to condoning them, to giving them active support.

In many of the subplots of the politics of the Middle East, Saudi Arabia is pivotal. Since King Salman succeeded to the throne in late January, he has been notably more anti-Iranian in his policies than his more judicious predecessor. And Salman’s activist young defense minister—and son—Mohammed took the anti-Iran campaign to terrible new heights with his decision in March to use the Saudi air force against the allegedly Iran-backed Houthi insurgency in neighboring Yemen. You might helpfully think of Yemen, with its large and impoverished population packed into a small corner of the Arabian Peninsula’s landmass, up against the sea, as being “Saudi Arabia’s Gaza.”

And five months of terrible bombings later, Saudi Arabia, with all its riches and its super-advanced and U.S.-supplied weaponry, has been just as incapable of forcing Yemen’s 28 million people to “cry uncle” as Israel has been with the Palestinians of Gaza.

Untangling a Tangled Web

More troubling were the increasingly bellicose threats Netanyahu started making, to the effect that if the United States would not take military action against Iran, then Israel might have to, itself.

The Middle East of 2015 is indeed a tangled web, with the region’s complex political/diplomatic situation balanced atop a churning sea of human misery and roiling social/economic collapse. It’s not just Yemen. Iraq is still reeling from the aftershocks of the 2003 U.S. invasion and the sectarian system U.S. occupiers introduced there. Syria is completely broken apart. Palestinians within and outside their homeland eke out lives burdened by continuing Israeli assaults and chronic, deep despair. Egypt groans under the vicious counter-revolution the Saudis bankrolled there in 2013. Libya’s collapse into (often jihadi) warlordism gives the lie to all that fine rhetoric Hillary Clinton once used about the necessity of using force to “save Libyan lives.”

It would thus be foolish to think that any one development like Washington and the other powers’ conclusion of a deal with Iran could speedily improve the situation of the Middle East’s peoples. If the accord prevents the outbreak of yet another extremely harmful war in the region, that is already a plus. And if it paves the way for better international cooperation on issues like Syria or Palestine, that will be great. Where the Vienna Agreement really has a serious impact on the international scene is, I think, at the broader level of the relations among the world’s great powers and the norms of international conduct.

Regarding norms, it is important to note that this agreement reinforces the importance of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and reinstates U.S. support for the kind of “universalist” approach to diplomatic challenges that the NPT embodies. Despite the treaty’s division of the world’s states into those that are allowed to have nuclear weapons and those that are not, there are reciprocal sets of commitments that all of them are required to make. However for over 20 years—that is, since President Clinton came to see the United States as having definitively “won” the Cold War—Washington’s policy on nuclear proliferation has drifted away from the universalist and reciprocal approach of non-proliferation, opting increasingly instead for the more militaristic and unilateral approach of counter-proliferation. Practitioners of counter-proliferation ignore international agreements and use their own means, including military force or cyberwarfare, to destroy projects to which they object in other countries. (This approach has, not coincidentally, been pursued by non-NPT member Israel for many decades.)

The Vienna Agreement breathes new life into the NPT. At the same time, it brings the United States more firmly back into the “community of nations” concept which has provided a valuable, if highly imperfect, organizing principle for international relations since 1945. The important point is that the whole “P5+1” group, along with a representative of the European Union, conducted the negotiation with Iran. The “P5” are the five permanent members of the Security Council, of which the United States is only one. And it will be the whole of the P5+1 that will be holding both Iran and the United States accountable for their compliance with the agreement. Of course the Tea Party and its allies in the Republican Party hate the idea that any non-Americans might ever seek to hold the United States accountable!

This agreement, then, is much bigger in its impact than “just” the technical questions of how many centrifuges Iran will have to mothball or how many days the IAEA will have to wait before it forces an unwanted inspection. It will almost certainly bring significant benefits to Iran’s 79 million people. It will prevent Americans from getting dragged by Israel into another devastating war. It paves the way for some reduction of tensions elsewhere in the Middle East. But most important, as it proceeds, it will pull our government, our political elite, and most of our society back into a relationship with the rest of the world that is more constructive, egalitarian, and respectful than the raw triumphalism and unilateralism that has held sway here since 1993.

Helena Cobban is an author, researcher, and founding owner of Just World Books.

This article will appear in the September 2015 issue of The Washington Spectator.

Illustration by Edel Rodriguez.

Marvelous, succinct and important commentary. Thank you for this Helena.

Lillian Rosengarten,

author “Survival and Conscience” (Just Word Books, Oct 5, 2015)