By Before things get any worse under President Trump, Washingtonians ought to pack up and move, and not just household by household.

Trump and the Republican-led Congress pose such a threat to the District of Columbia’s roughly 700,000 residents that the city should push for a return to Maryland, which long ago ceded land for use as the seat of the federal government.

The idea, known as retrocession, has been around since the earliest days of the Republic. It already happened with Virginia. Like D.C. statehood, a Maryland retrocession would face enormous legislative and legal hurdles, but it’s arguably more realistic, especially now.

The District, lacking representation in Congress except through a nonvoting delegate, is uniquely at the mercy of the federal government at a time when President Trump and his MAGA followers seem bent on authoritarian rule. “We should take over Washington, D.C.,” he boasted.

While the District’s lack of voting rights has always been a problem, one could argue that statehood has been a cruel fantasy for just as long—one sustained in recent years almost entirely on the wish for two shiny new Democratic senators, not political or constitutional realities. Given the current reality of Trump’s sustained attack on its self-governance, the District can’t afford to keep hoping for divine intervention to make it the 51st state.

MAGA’s most visible affront to the city occurred when Mayor Muriel E. Bowser caved over Black Lives Matter Plaza, a street mural created during racial justice protests after George Floyd’s murder. The plaza, which was intended to be permanent, became a colorful symbol of the District’s defiance during Trump’s first term. The city ripped up the plaza in March after Republican lawmaker Andrew Clyde of Georgia threatened to withhold millions in transportation funding if the plaza wasn’t removed.

Trump also ordered Bowser to do something about crime and graffiti, and demanded that Bowser clear out homeless encampments, complaining that there were “too many tents on the lawns” and suggesting federal officials would step in if the city didn’t.

The Trumpian threat to the District has been apparent since the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, when the mayor, lacking the powers of a governor, could not summon reinforcements from the D.C. National Guard.

With this as prologue, Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.) recently revived the idea of Maryland retrocession. The procedure would require Maryland’s approval, among other things. It’s also not clear that retrocession would pass constitutional muster, despite Virginia’s example. But it’s arguably a safer bet than D.C. statehood.

D.C.’s unique—some might say tortured—status as a federal enclave goes back to the nation’s founding. The Framers believed the seat of the federal government should be independent, subject only to Congress, and free of undue influence from any state.

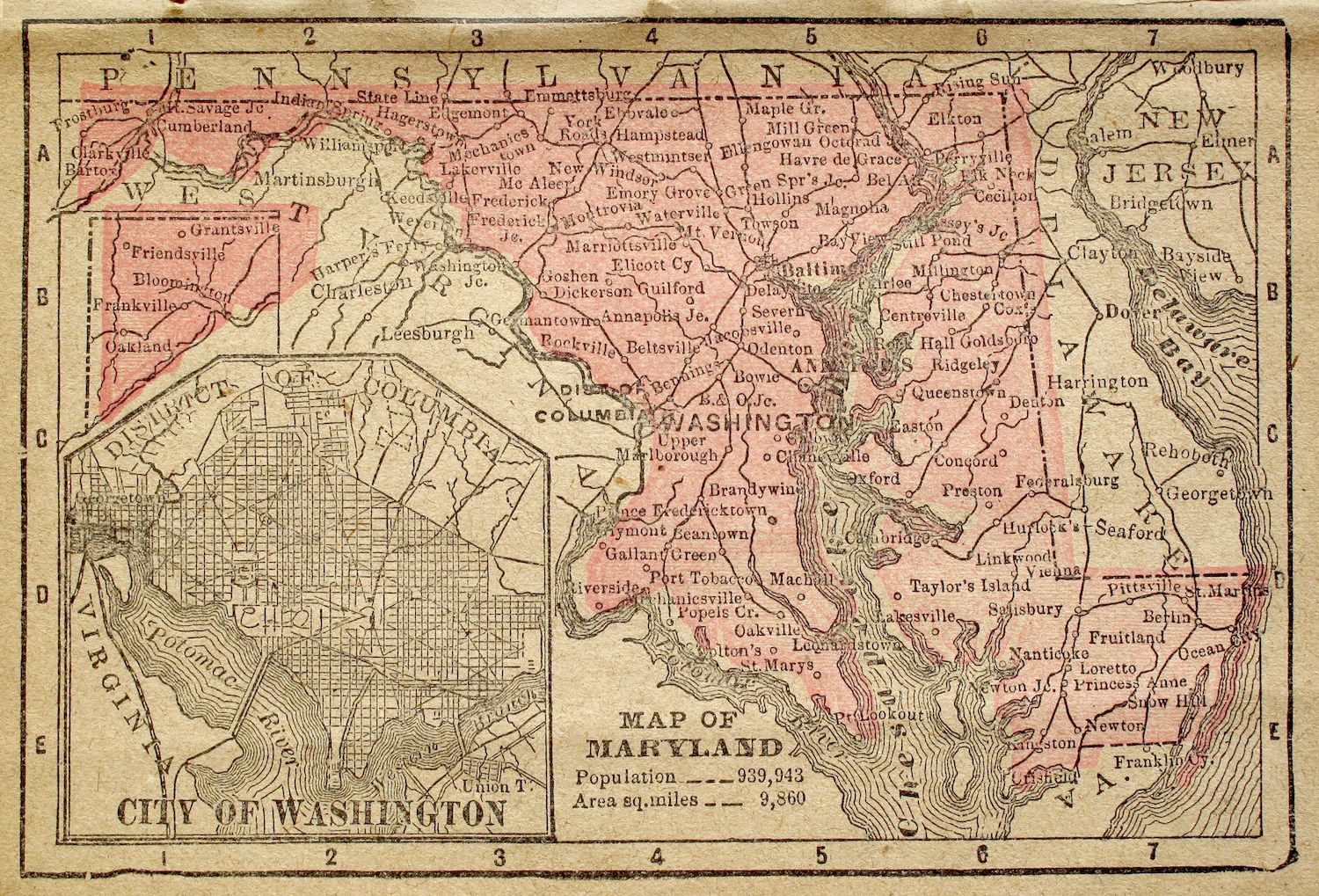

The result, enshrined in Article 1, Section 8, of the Constitution, grants Congress “exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever” over the district. It also stipulated that the District be no more than 10 miles square. The Maryland General Assembly ceded land for the federal enclave in 1788; a year later, Virginia followed suit with land along the Potomac River. Congress moved to the District in November 1800.

From the first, there were concerns about disenfranchisement of the enclave’s citizens. No less than Alexander Hamilton argued that the District should receive congressional representation when its population reached a certain size. But his proposal went nowhere.

Virginia soon began clamoring for the return of its land, driven partly by fears the federal government might abolish slavery there. In 1846, Congress complied, returning what is now the city of Alexandria and Arlington County. The Supreme Court, asked to rule on the legality of the return nearly three decades later, let the transfer stand. But the high court also left unsettled the question of whether Virginia’s retrocession was constitutional.

Since then, several efforts have been made to address the District’s limited voting rights. The 23rd Amendment, ratified in 1961, allowed D.C. to vote for president. The District received three electoral votes, or no more than those given to the smallest state.

In 1973, Congress passed the Home Rule Act, allowing D.C. to elect a mayor and city council. But Congress also held onto veto power, as demonstrated when a D.C. crime bill was overruled with President Biden’s help two years ago.

Another major push for voting rights came in August 1978, when Congress endorsed a constitutional amendment that would have allowed District residents to participate in all federal elections. But the proposed amendment failed, spectacularly. Only 16 states ratified the measure, well shy of the three-quarters necessary to amend the Constitution. The reasons for its rejection still sound familiar.

Opponents derided Washington as a “company town,” whose sole industry was government with an area smaller than Rhode Island. Others doubted whether the District could ever be on sound financial footing. But the late Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass) blamed racism. D.C., he said, was seen as “too urban, too progressive, too Democratic, or too black.”

But opponents said their objections were practical and constitutional, and had been raised when the District was majority white. Even Democrats in some non-ratifying states said they simply voted against diluting their political power.

“Why should we give more votes to the East?” Montana Governor Thomas L. Judge, a Democrat, offered at the time.

DC statehood advocates then decided on another route to statehood already taken by seven states, beginning with Tennessee. The “Tennessee Plan” relies on Article IV, Section 3, which grants Congress authority to admit new states through a simple act of legislation.

In 2019, Democrats introduced H.R. 51 to admit D.C. as a state, casting it as an issue of civil rights. The idea would be to shrink the federal enclave to an area with the Capitol, the National Mall, the White House and most federal monuments and declare the rest of the city a state.

The legislation included a provision to expedite repeal of the 23rd Amendment, lest the country could be left with an absurdity: the rump federal enclave, including the occupant in the White House, having as many votes for president as the smallest states.

Republicans saw H.R. 51 as a “power grab,” saying Democrats were more interested in gaining two new senators to tilt the balance of power than in addressing civil rights or the inequity of taxation without representation.

Opponents argued that, although Congress had admitted dozens of states into the union through simple legislation, none—unlike the District—owed their existence to a separate clause in the Constitution.

In June 2020, the House passed H.R. 51, marking the first time either chamber of Congress had approved D.C. statehood. It died in the Senate. The measure is back this year, but it’s hard to imagine it ever getting past President Trump.

It’s just as hard to imagine that Americans, so deeply polarized now and likely to be that way for the immediate future, would agree on D.C. statehood and all that comes with it, including the necessary passage of a constitutional amendment. But they might be persuaded to let the District go back to where it came from.

Fredrick Kunkle is a former staff writer for The Washington Post. He also has worked at The Bergen Record of New Jersey, The Star-Ledger of Newark and is the author of Pray for Us Sinners: The Hail Mary Murder. His short fiction has appeared in the Virginia Quarterly Review and the Masters Review Anthology. He is a graduate of Yale University and lives in Washington, D.C.

0 Comments