Some 28 months back, I began my first article for The Washington Spectator by reflecting on the big news everyone was talking about those summer weeks, the new wrinkle in the saga of America’s four-century racial ordeal: it was July 9, and South Carolina had removed the Confederate flag from the statehouse grounds. It’s easy to forget what a huge story it was, all those months ago.

An awe-inspiring speech from a member of the South Carolina state assembly, bursting into tears, announcing herself as “a descendant of Jefferson Davis,” begging her colleagues to remove the flag (“I have heard enough about heritage!”) became a viral video hit of the summer.

The issue dominated the week in Washington. The night before the flag-removal bill was signed by the Palmetto State’s governor, House Republicans, in the wee hours when they hoped no one was watching, introduced an amendment to reverse a previously passed Democratic measure banning Confederate flags in national parks and federal cemeteries. House Democrats, decrying the perfidy, marched shoulder to shoulder carrying Confederate flag placards, in a backlash so immediate and fierce—and popular—that the next morning the House majority leadership canceled the vote on the Interior appropriations bill containing the offending amendment.

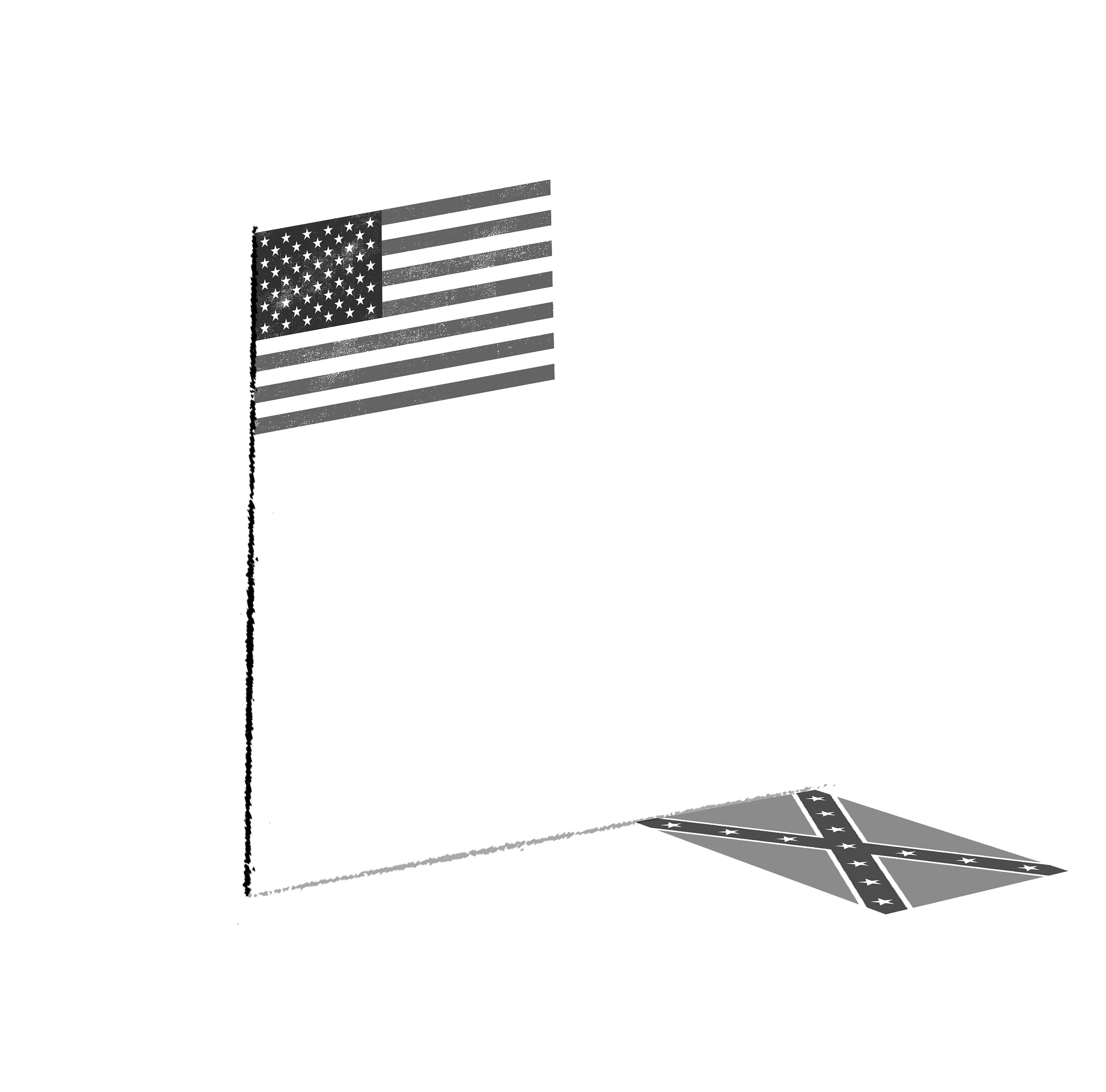

“Suddenly, with a single flap of the Angel of History’s wings, America has experienced a shuddering change,” I wrote then. “The American swastika has finally become toxic—a liberation that last month seemed so impossible that we’d forgotten to bother to think about it.”

It’s easy to forget how the drama was greeted as a kind of revolution, the sort from which there could be no turning back, because the other event that same summer, some three weeks earlier, looms so much larger now: Donald Trump announced his campaign for the presidency with a speech of such over-the-top racism it could have made even a Confederate blush.

That debut may carry colossal implications now, but back then it was hardly more than a sideshow. “Why Donald Trump Isn’t a Real Candidate, in One Chart,” fivethirtyeight.com immediately pronounced. The chart showed Trump’s position far at the bottom in polls, conducted since 1980, of candidates’ popularity among party members in the June before primaries, and demonstrated that “Trump has a better chance of cameoing in another Home Alone movie with Macaulay Culkin—or playing in the NBA finals—than winning the Republican nomination.”

This inaugurated a tidal wave of Trump dismissals that included—to pull a few examples, seriatim, from a Google search I just did of “Trump isn’t” and “Trump won’t,” from the days between his announcement and November 9, 2016—“Donald Trump Isn’t Going to Be President” (Slate, May 4, 2016); “Relax, World. Trump Isn’t Going to Be President, but He’ll Rinse Some Cash From His Run” (Huffington Post, July 8, 2016); “Donald Trump Isn’t the Presidential Candidate We Should Be Worried About” (The Nation, June 27, 2016); “Trump Isn’t Real” (The New York Times, February 2, 2016); “Here’s Why Trump Won’t Win the Republican Presidential Nomination” (The Guardian, August 22, 2015).

Trump, chump: end of story.

Me, at the time: I saw the story differently. Not that I had any special clairvoyance concerning Trump’s prospects: I thought no more than any of the rest of the scribbling mob of his chance of winning. I didn’t so much disagree when editors suggested I turn my attention instead to other, likelier aspirants. It was more like I couldn’t help it: I was finding Trump’s ascendency far too compelling to pay attention to anything much else.

And it was the spectacle of the celebration of the removal of the Confederate flag from the South Carolina capitol, and Trump’s horrible imprecations that Mexico was sending its rapists to America, that launched my fascination. The juxtaposition said so much about what I find so important to understand about America: its ceaseless longing for innocence—especially racial innocence.

It is a ritual we are forever primally compelled to repeat. In my book Before the Storm, about the 1964 presidential election, I reproduce a headline from The New York Times that followed Barry Goldwater’s defeat to Lyndon Johnson: “White Backlash Doesn’t Develop.” The summer before the election, of course, LBJ had signed the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act outlawing segregation in public accommodations: Barry Goldwater voted against it; Barry Goldwater lost in a landslide—and voilà: America’s racial ordeal, healed at last!

Of course, as I went on to point out, that same day of Lyndon Johnson’s landslide victory, in which he took California by about a million votes, California passed an initiative, also by about a million votes, to strike down a state law against housing discrimination.

The next month, lighting the White House Christmas tree, LBJ pronounced these “the most hopeful times in all the years since Christ was born in Bethlehem.” He said, “I want all men, everywhere, to know that the people of this great nation have but one hope, one ambition towards other peoples: that is to live at peace with them.” (He was, at that very moment, drawing up bombing targets for an escalation of America’s covert war in Vietnam.) He said, “There has been brought into the affairs of man a more generous spirit toward his fellow man.” (Perhaps he had forgotten that during the election season just past, his campaign abandoned promoting his achievements in civil rights as a campaign theme, fearing—yes—a white backlash.)

Then, on August 6, he signed the Voting Rights Act. “Three and a half centuries ago the first Negroes arrived at Jamestown,” he said. “And today we strike away the last major shackles of those fierce and ancient bonds. Today the Negro story and the American story fuse and blend.”

Yes, that’s right. The president of the United States, under the Capitol dome, with Martin Luther King in attendance, officially announced that racism in America was finished. African Americans disagreed. As I related in my next book, Nixonland, rioting in Watts began five nights later. Los Angeles police—many of them recruited by the racist police chief William Parker from the Mississippi Delta region, pretty much for just that purpose—responded with guns blazing, killing 34.

Trump is president and the American swastika, instead of being removed, has been planted more firmly than at any time in decades. That template—American innocence proclaimed one day, American carnage following the next—is as much a part of our national character as blues, boogie-woogie, and mass disbelief in global warming.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not claiming immunity myself from the temptations of innocence. I’m an American, after all, too.

In August 2015, I wrote here about another symbol. Inspired by the triumph in South Carolina, I hoped to spark a movement to banish a flag that, like the American swastika, “supposedly honors history but actually spreads a pernicious myth,” of greatest use “to venal right-wing politicians who wish to exploit hatred by calling it heritage.” I was talking about the POW/MIA flag, and, repeating a story I’d told in my most recent book, The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan, I recalled how “Richard Nixon invented the cult of the ‘POW/MIA’ in order to justify the carnage in Vietnam in a way that rendered the United States as its sole victim.” The core of this cynical ploy was to instill in the public the notion that, first, during the war, the enemy was hiding as many as 1,200 more U.S. personnel who had been classified as “Missing in Action”; and then, after the war, that the MIA still might be out there. And the flag, which depicts one such forlorn prisoner in silhouetted profile, with the legend “YOU ARE NOT FORGOTTEN,” implies that Vietnam just might still be holding U.S. prisoners, even though by any responsible, sane accounting this makes absolutely no sense.

I pointed out that for all the torture suffered by the several-hundred American prisoners of war in North Vietnam (most of them pilots whose bombs had killed civilians), the several-thousand prisoners held by our South Vietnamese allies, in prison camps built and maintained by us, which contained many who had done nothing but advocate for peace, were tortured far more severely. One South Vietnamese official, confronted with the testimony of survivors, responded with incredulity: “No one comes from the tiger cages alive.” Then, in a final twist, back here in the USA, Americans heard reports about these underground “tiger cages” maintained by our allies, on whose behalf we were expending all this blood and treasure, and turned it all around in their minds, coming to believe that it was Americans who were held in tiger cages.

I labeled that, in the original version of the story, “racist.” In a second version, with an apology appended, I retracted the word. Back then I didn’t explain why. The reason was all the death threats.

Just now, I spent an hour tearing through the closets of my house trying to find my file of these threats, which I assembled to take down to the police station when I filed my report. Then I remembered I threw them out, because I didn’t want my wife to stumble upon the avowals of delight that one fellow said he’d take in watching my skin flayed from my body, or the description of the arsenal with which another promised to erase my existence.

Now, some criticisms I received from Vietnam veterans were respectful and thoughtful, and I learned from them, though what I learned only redoubled my confidence in my underlying argument. The Vietnam War, many Americans (who didn’t know it before) are now learning from Lynn Novick and Ken Burns’s epochal PBS series, was at its essence a project of sending young men thousands of miles from home to destroy their bodies and souls in ways from which they would never recover. They would come home to an ungrateful nation that turned on them. (One of the most fascinating things I’ve learned in my years of researching Vietnam was that the greatest perpetrators of this betrayal were not the anti-war activists, who often embraced returning veterans, but the old codgers and coots at the nation’s Veterans of Foreign Wars and American Legion halls, who despised Vietnam veterans as losers.) I learned that many Vietnam veterans identify so very, very deeply with the POW/MIA flag as their flag: a lone symbol, amid all the rejection and pain, that acknowledges them.

It’s a particularly American sort of paradox. The government treated them as cannon fodder in a war built on lies. Then, upon their return, it did not give them the care that they needed. (Nixon cut programs for veterans’ services.) It gave them a flag. This flag the maligned Vietnam veterans clasped to their bosom and defended with savagery against those, like me, who dared point out the con.

This, as I say, I only understood later. At the time, I was far more naïve: flush from the newborn discrediting of the Confederate flag, I imagined my article might ignite a movement of conscience to get the POW/MIA flag—which, for example, flies over post offices by federal law—taken down.

Clearly, I failed. Instead, this past summer, our president proclaimed September 15 “National POW/MIA Recognition Day”:

As commander-in-chief, it is my solemn duty to keep all Americans safe. I will never forget our heroes held prisoner or who have gone missing in action while serving their country. Today, we recognize not just the tremendous sacrifices of our service members, but also those of their families who still seek answers. We are steadfastly committed to bringing solace to those who wait for the fullest possible accounting of their loved ones….

That’s Trumpism right there: take some awful feature of America’s reactionary heritage, and renew it for a new generation in its most malignant imaginable form.

Never forget. Never forget that, whenever our childlike fallen nation seems most palpably ready to turn some corner toward maturity and reckon with the cruelties of our past, sloughing off the misguided rituals by which we reckon ourselves ever martyrs, never perpetrators, always victims, something awful is probably getting ready to barrel around the corner. American flags wave. They also waive: they waive history, reality, persecution—letting us get away with the murders of previous generations, so elites can better prepare hoi polloi for the next time they’ll be ordered to kill.

Rick Perlstein is The Washington Spectator‘s national correspondent.

Reprobate