Thinking several steps ahead prepares us for the future; not doing so invites failure. The inability to think ahead has turned a global health crisis into an economic crisis for the United States and a political crisis for President Trump.

Currently (early May), it is hard to know when the U.S. economy can safely reopen because we lack adequate testing to track the coronavirus and keep it from spreading once the lockdown ends. It is easier to identify what we’ll need to get our economy on track once the restrictions are eased. Success will depend entirely on money being spent.

With federal government aid injecting money into the economy, the greatest constraint on spending will be the high debt levels of consumers, businesses, and state and local governments. If this debt curbs spending, any economic recovery will be slow at best. At worst, it will result in another Great Depression. To prevent this, we must plan ahead and begin reducing debt now.

At the end of 2019, consumer debt exceeded $4 trillion, averaging $12,700 per person and 10 percent of take-home pay. Consumer debt is primarily credit card debt, motor vehicle debt, and student loan debt. Adding mortgage debt to this brings total indebtedness to around $14 trillion.

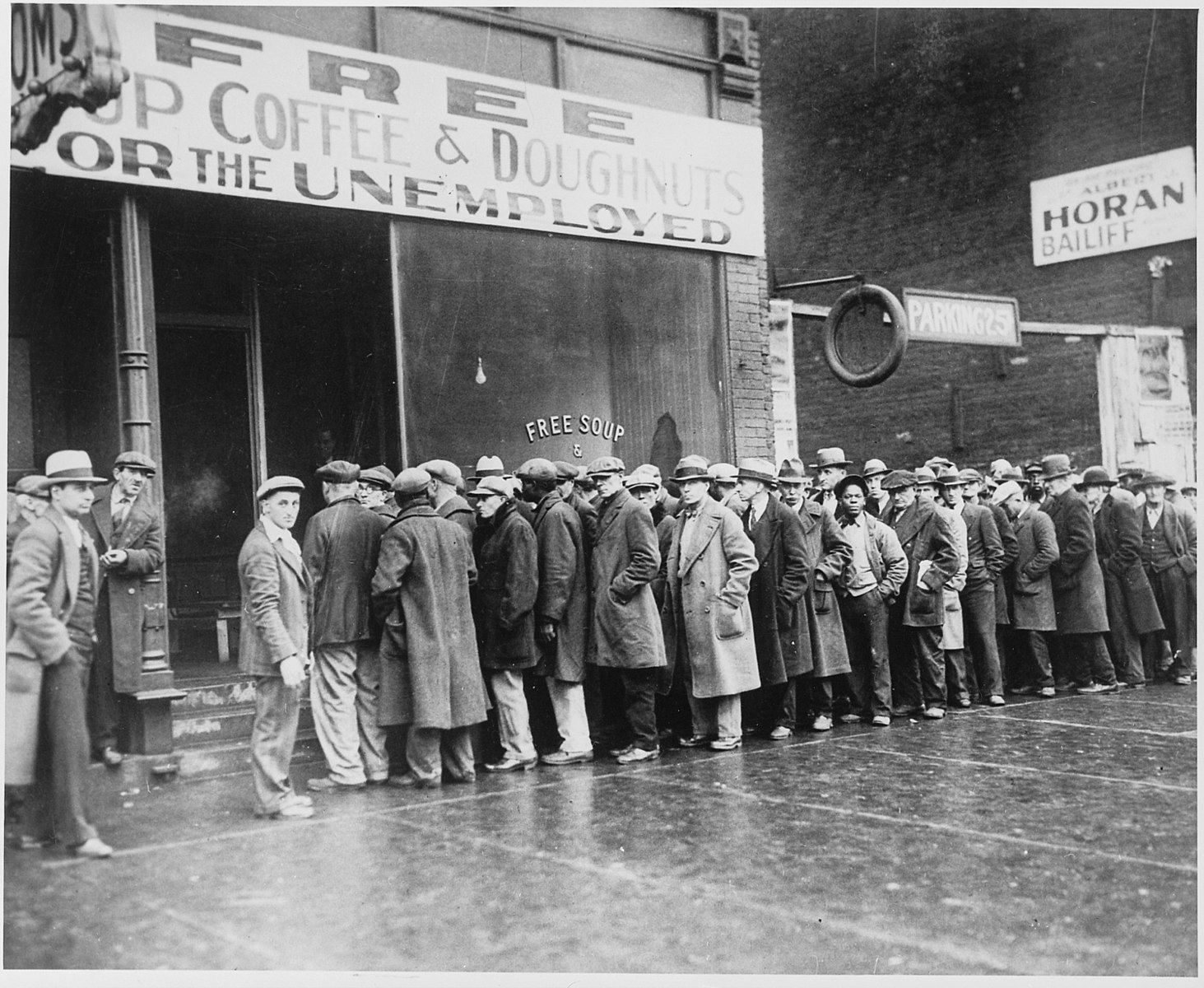

There is no doubt that debt levels are higher now than in late 2019. Although we lack actual data, many signs point to consumers in dire financial straits. Food banks are currently experiencing surging demand. Estimates of late mortgage or rent payments in April range from 15 to 30 percent, many times the normal rate. Moreover, in early April most people had been paid for a good part of March and had some emergency savings. Wages and savings have now largely disappeared for many Americans.

Consumer expenditures account for 70 percent of economic activity in the United States. Without robust consumer spending, it is hard to see how the U.S. economy could achieve robust economic growth. Consumer debt has to be reduced so people can spend more money once we end the lockdown. There are several ways to do this.

Another $1,200 check for each adult (plus $500 for each child) would help consumers repay their past debts and keep them from going even further into debt. Two more such payments would be better than one.

Unpaid rents and mortgages add to household debt levels and will have to be paid in the future. During the Great Depression, the government created the Home Owners Loan Corporation to refinance the one million mortgages in default and work with homeowners so that they would be able to pay their obligations. When this New Deal program ended, the government actually made a little bit of money. More importantly, people were able to remain in their homes. Something similar should be done now—both for homeowners and renters.

But substantially more is required. The 2005 bankruptcy reform made it harder for Americans to declare bankruptcy. Many can only file for Chapter 13 bankruptcy, which reduces some consumer debt, rather than Chapter 7, which eliminates it all. The minimum allowable period between one Chapter 7 bankruptcy and another also was increased from six to eight years in 2005. A top priority should be a temporary moratorium on the time period required between bankruptcies, enabling people deep in debt to start afresh as the economy reopens. Further, we should permit college debt to be discharged or reduced in bankruptcy, just like any other type of consumer debt.

Contrary to what many people think, bankruptcy won’t prevent people from borrowing and spending money. After discharging debts through Chapter 7, people can’t refile for another eight years. This plus a lack of debt makes them good credit risks, which is why they frequently receive preapproved credit card offers once the bankruptcy is final.

Making it easier for people to wipe out their debt would also help small businesses, since these are owned by one person or a few people. Less personal debt makes it easier to borrow to restart their business. The Paycheck Protection Program helped small businesses but only a little bit. Three-fourths of all the money received had to go to maintain previous payroll if the government loan was to be forgiven; this left little money to fund other business expenses like rent, insurance, and utilities.

And the government frequently bails out large firms in great debt that are about to go under. If a given industry is crucial for the U.S. economy and suffering from the economic impact of the coronavirus, there is nothing wrong with bailing out the firms in that industry. However, we should have learned from the Great Recession that we can’t just bail out corporations. Some quid pro quo is needed, such as a moratorium on dividend payments and stock buybacks plus limits on executive pay.

Finally, grave problems face state and local governments.

Almost every state and local government in the United States must balance its budget annually (except for public investments, such as building schools and infrastructure construction). To handle economic downturns, state and local governments maintain rainy day funds. At the beginning of 2020, these averaged nearly 8 percent of annual spending, enough for a typical recession but not nearly enough for now.

Consensus forecasts predict the U.S. economy will shrink by close to 8 percent this year; more pessimistic projections call for double-digit declines in gross domestic product. If tax revenues fall by an equal percentage, state and local government budgets will be pushed into the red as a result of reduced tax receipts. At the same time, state spending obligations (unemployment insurance, Medicaid, and hospitals) have soared. Some state and local governments have already frozen or reduced spending. This will lead to layoffs of teachers, police, trash collectors, and other government employees and put a damper on any economic recovery. Neither the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act nor the supplemental spending bill passed in late April help state and local governments. Correcting this oversight must be a top priority.

Since no one else can spend, we must look to the federal government—despite the high levels of federal debt at present. With the Federal Reserve willing to buy new government IOUs, the federal government can borrow whatever it needs at near-zero percent interest in order to reduce the indebtedness of consumers, businesses, and state and local governments. In addition, the federal government itself needs to plan ahead, with a set of spending programs to help the economy grow once the lockdown ends. Infrastructure, education, fixing antiquated state unemployment insurance systems, and medical research and preparedness should be at the top of the list here.

The relief bills passed in March and April will increase the federal budget deficit this year from $1 trillion (pre-coronavirus) to $4 trillion. Congress is currently debating another $1 trillion in spending, which is likely to include aid to local governments. While this will far surpass all previous deficit records, our economic health is much more important than several trillion dollars of additional federal government debt. We do not really have a choice.

Tax revenue to repay government borrowing will come once the economy recovers; and taxes can be raised when the U.S. economy fully recovers. Excessive worries about budget deficits or the level of federal government debt will condemn us to a slow and difficult recovery, as was the case following the Great Recession. Let’s not make the same mistake again.

The author is professor of economics at Colorado State University; author of Fifty Major Economists, 3rd edition (Routledge, 2013) and Understanding Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century (Routledge, 2015); and president of the Association for Social Economics.

0 Comments