Artwork of Southern Artists of the Vietnamese Diaspora

Ogden Museum of Southern Art

New Orleans

March 15 -September 21, 2025

Ogden Museum of Southern Art commemorates the 50th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon with Hoa Tay (Flower Hands), an exhibition which centers emerging and established Vietnamese- American artists working throughout the American South. These artists use diverse media and styles to forge their own distinctive vision, conveying narratives of the Vietnamese Diaspora, both personal and universal.

On April 30, 1975, the People’s Army of Vietnam and the National Liberation Front of Vietnam seized the city of Saigon which definitively marked the end of the Vietnam War and the surrender of the Republic of Vietnam. Subsequently, this resulted in a mass exodus of Vietnamese people who were forced to flee their country due to political persecution. One and a half million people risked their lives crossing borders into neighboring countries Laos and Thailand, while others embarked on treacherous boat voyages in the pursuit of sanctuary. A large portion of the Vietnamese diaspora sought refuge throughout the United States, initially relocating to any region offering sponsorship. Many of these refugees permanently settled throughout the American South, including enclaves in Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, Oklahoma, Virginia, North Carolina and the District of Columbia. The Gulf Coast was particularly favored due to the similar subtropical climate and access to familiar shrimping and fishing industries.

The anniversary of the Fall of Saigon, or Black April, is often viewed as a somber emblem for the loss of war, homeland and family. It is simultaneously regarded as the initial establishment of Vietnamese communities within the American cultural landscape. The generations which followed have had to grapple with the effects of displacement and assimilation into American culture, all while facing systemic racism, anti-Asian sentiment and the weight of collective trauma. That said, the Vietnamese-American people have demonstrated tremendous resiliency and determination. Vietnamese-Americans have significantly influenced the region’s culture through their contributions to the culinary arts, beauty industry, literature, fine arts and music. Half a century later, the catalytic influence of the Vietnamese community is an integral force in the evolution of a new Southern identity.

In Vietnam, a child is praised if they have many whorls on their fingertips. Similar to the rings that grow every year on tree trunks to mark a passing age, the more circles a Vietnamese child has on their fingertip, the more artistically gifted they are believed to be. Hoa tay, loosely translated to ‘flower hands’, are considered the marks of ingenuity, spirit and talent in the arts. Even among those with hoa tay, no one has the same fingerprint patterns. The artists in this exhibition are no exception—each bringing a singular vision to their studio practice.

As a whole, the work in this exhibition often contends with complex notions of displacement and the formation of a unique cultural identity. Using a broad range of media and styles, these artists parse through the nuanced duality of their own unique Vietnamese-American experiences within the equally fraught history of the American South. Through that exercise of self-examination, each of these artists confront the past, embrace the future and bridge the reconciliation of both. The task of looking inward and forward at once seems impossible yet necessary – an exploration in rebirth that is often a byproduct of grief. The act of witnessing comes in unexpected forms, as these works wrestle with an inherited legacy that is both violent and resilient. Through material and form manipulations, these artists extract the truths and experiences of both visibility and invisibility, delicately balancing a path forward through sometimes fond, sometimes treacherous memories. But above all, it is a path forward.

With thanks to the Ogden Museum of Southern Art for permission to reproduce images and texts, the Washington Spectator presents this small selection from their exhibit Hoa Tay (Flower Hands) which brings these artists into dialogue with one another as a tribute to this monumental moment of fifty years in the United States.

The curators of Hoa Tay are Selina McKane, Uyên Đinh, and Bradley Sumrall. The Ogden can be found at 925 Camp St, New Orleans, LA 70130. Bradley Sumrall, Curator of the Collection, can be reached at [email protected].

Click to enlarge

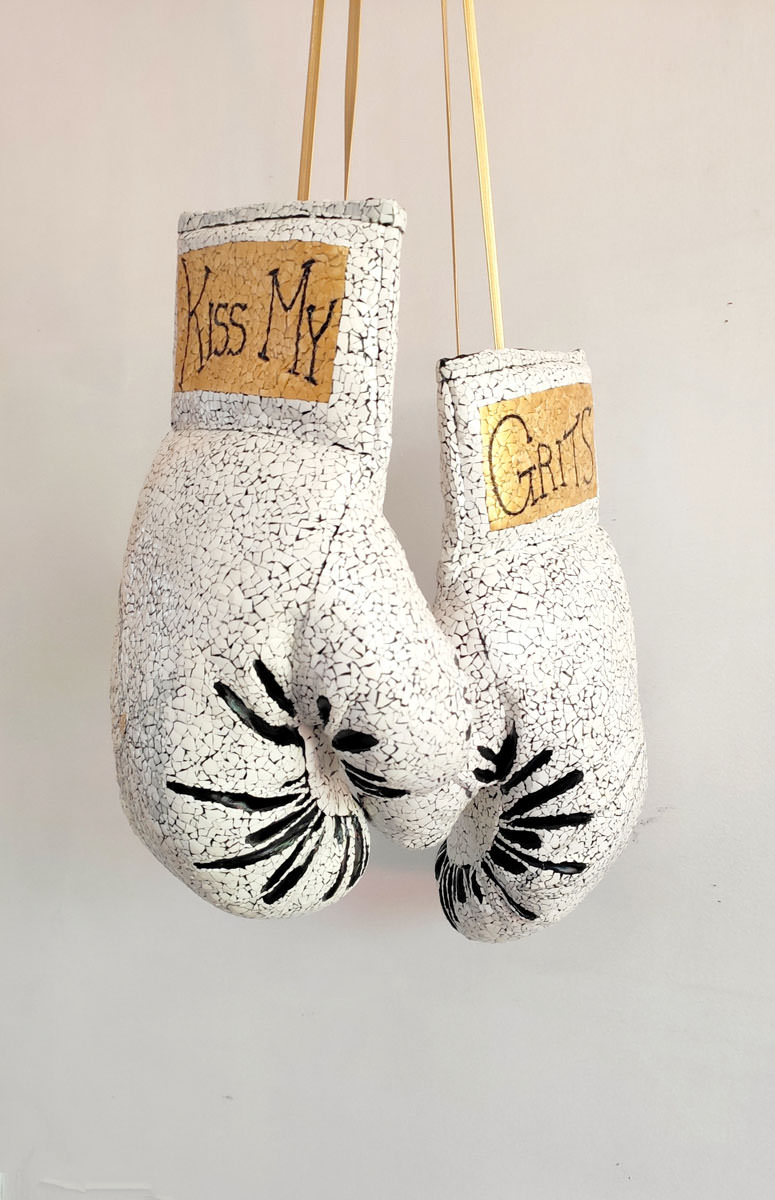

MyLoan Dinh

Kiss my Grits

2024

Boxing gloves, eggshells, acrylic

18 x 13 x 5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

MyLoan Dinh (b. 1972, Saigon, Vietnam) is a multidisciplinary artist whose work explores themes of place, identity, visibility and human connection, while confronting issues of racism, sexism and the legacy of colonialism in contemporary culture. Sagaciously incorporating traditional craft methods into her contemporary art practice, Dinh often transforms deeply personal objects and experiences into iconic symbols and narratives of universal relevance. She currently lives and works in Charlotte, North Carolina and Berlin, Germany.

Kiss My Grits is the latest work in MyLoan Dinh’s Boxing Glove Series, and was created in response to the title of this exhibition, Hoa Tay (Flower Hands). Borrowing from the traditional Vietnamese Sơn mài lacquer painting tradition, she delicately transformed a pair of boxing gloves with eggshell. The title, Kiss My Grits, is drawn from a deeply Southern expression of defiance made famous by the character Florence Jean “Flo” Castleberry on the 1970s sitcom Alice. The very subtle details on the front of the gloves are Magnolia Floribunda, a Magnolia species native to Vietnam, Laos, Thaliand, Myanmar and Southern China. “When I think about Southern identity and flowers of the American South, Magnolias certainly come to mind” Dinh says. “The flower has many meanings across different cultures – including strength and endurance.”

MyLoan Dinh on The Boxing Glove Series:

“This series engages with timely complexities of the contemporary US-American Zeitgeist. I explore questions of gender and race through objects and representations that carry evocative associations.

The series probes our changing, and at times volatile, cultural consciousness on several levels—foremost through a set of tensions. I glued eggshells on boxing gloves, and brought them together with politically-resonant embroideries. Boxing gloves, though physically soft, traditionally bear connotations of force, violence and masculinity. Needlework, by contrast, is traditionally associated with femininity and delicateness, though its main tool is sharp and piercing. Moreover, the eggshells, whilst fragile, also evoke shelter, nourishment and fertility in a very basic and physical sense. The processes of cross-stitching and covering objects in eggshells require time-consuming labor, care and intentionality.

The texts clearly disclose my want for equality and a balance of power; this much should be uncontroversial. But what these words mean exactly, let alone how we might realize them, remains unclear. Our personal involvements, internal and external, in struggles for freedom and equality are difficult to navigate; as an immigrant and woman of color, I cannot separate myself from these quandaries.

Many widely-understood questions are asked, but I provide no concrete answers—just dives, stabs and punches.”

Click to enlarge

Christian Đinh

In the mud, what is more beautiful than a lotus?

Porcelain and silk

16 x 16 x 6 inches

Gift of the artist

In the mud, what is more beautiful than a lotus? is the ninth set of hands within Christian Đinh’s series Nail Salon. This series illustrates the ways in which the Vietnamese nail salon industry in the United States embodies the success of the Vietnamese-American community. Each set of hands within Đinh’s series are porcelain casts of display hands routinely found in nail salons, which become elevated objects through his use of fine porcelain and silk. Southeast Asian fine porcelain and silk were luxuries, whose artistries are still traditionally passed from generation to generation. Furthermore, Đinh seeks to bridge those traditions with the Vietnamese diaspora in the United States subsequent to the Vietnam War.

Similar to the Vietnamese-American culture in Louisiana, In the mud, what is more beautiful than a lotus? weaves the Mississippi River Delta culture in the American South and the Mekong River Delta culture in Vietnam.

The pearlescent glaze on the tips of the fingernails and the rim of the forearms reference both pearl cultivation in the Mississippi River in the early twentieth century and traditional Vietnamese pearl inlay. The Mississippi River pearls harvested from mollusks native to the region were primarily used for buttons, however pearls have historically existed as a symbol of beauty in many regions in the South. Simultaneously, in Vietnamese culture, pearl inlay is a common decorative technique that requires hand cut pearls, which are then embedded into lacquered and precisely carved wood. Furthermore, Đinh seeks to reference the pearl inlay decorative ware commonly found within Vietnamese-American households.

Located on the inner forearms, is a traditional Vietnamese ca dao, meaning song without music. The ca dao inscribed on the hands is as follows:

Trong đầm gì đẹp bằng sen

Lá xanh bông trắng lại chen nhụy vàng

Nhụy vàng bông trắng lá xanh

Gần bùn mà chẳng hôi tanh mùi bùn

In English, the ca dao translates to:

In the mud, what is more beautiful than a lotus?

Green leaves, white flower covers a yellow center

Yellow center, white flower, green leaves

Close to mud but never smells as mud

The lotus flower is the national flower of Vietnam, as the flower represents beauty, longevity, and resilience to the Vietnamese people. Lotus flowers are native to both the swamps and bayous of the Mississippi River Delta and the vast floodplains of the Mekong River Delta. In the ca dao, the lotus is described in the second line as “Green leaves, white flower covers a yellow center” and mirrored in the third line as “Yellow center, white flower, green leaves.” Đinh interprets this reflection as directly connected to the duality of the regions and the Vietnamese-American experience. Like the lotus and the pearl, the Vietnamese-American community is deeply and beautifully intertwined within the region.

Click to enlarge

Đan Lynh Phạm

I Bear the Fruit of My Ancestors

2021

Limited edition screen print

11 x 14 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Đan Lynh Phạm (b. 1993, Saigon) is a Vietnamese interdisciplinary artist and illustrator. Born in Vietnam and raised in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Phạm received her BFA in Studio Arts with a focus on watercolor and sculpture at Oklahoma State University. Phạm creates a unique blend of graphic language with Vietnamese art traditions, employing an analytical approach to art-making. Her artistic practice serves as a visual diary, integrating 2D and 3D elements to delve into her ongoing exploration of identity, socialization, and her experiences growing up as a child of refugees.

Đan Lynh Phạm (sinh năm 1993, Sài Gòn) là một nghệ sĩ và họa sĩ minh họa liên ngành người Việt Nam. Sinh ra tại Việt Nam và lớn lên tại Tulsa, Oklahoma, Phạm đã nhận bằng Cử nhân Mỹ thuật chuyên ngành Nghệ thuật Xưởng với chuyên ngành màu nước và điêu khắc tại Đại học Tiểu bang Oklahoma. Phạm tạo ra sự pha trộn độc đáo giữa ngôn ngữ đồ họa với truyền thống nghệ thuật Việt Nam, sử dụng phương pháp tiếp cận phân tích để sáng tác nghệ thuật. Thực hành nghệ thuật của cô đóng vai trò như một cuốn nhật ký trực quan, tích hợp các yếu tố 2D và 3D để đi sâu vào quá trình khám phá liên tục của cô về bản sắc, xã hội hóa và những trải nghiệm khi lớn lên như một đứa trẻ tị nạn.

I Bear the Fruits of My Ancestors is a testament of life in its ritualistic commitment to honoring ancestral lineage. Based on the cultural practice of ancestral worship, the work centers the altar, a common fixture found in most Vietnamese households. The altar is a site of familial activities as much as it is a sacred space to honor those who have passed. The meticulously arranged altar usually includes photos of the deceased, along with offerings such as beer, fruits, and incense. Phạm speaks of this reciprocal relationship between the dead and the living that transcends time, “these altars serve as a tangible link to our ancestors. Daily rituals, including the lighting of incense, serve as poignant reminders of the transient nature of life.” The larger than life lanterns emulate the soft glow that often accompanies ancestral altars. The work is both an offering of gratitude to Phạm’s ancestors as well as a physical manifestation of the sweetness and perseverance that ancestral blessings have brought forth. Because history is consistently honored, the dead keep on living and existing beyond the boundaries of life, as being remembered is a way to be reborn. Though fruits are perishable, history will continue to course through the veins of the living, as Phạm pronounces, “The life that I am now living, the life of self-actualization, is owed to my parents, grandparents, and ancestors whose only choices were to survive and contribute to a better life for future generations.”

I Bear the Fruits of My Ancestors là minh chứng cho cuộc sống trong cam kết nghi lễ tôn vinh dòng dõi tổ tiên. Dựa trên tập tục văn hóa thờ cúng tổ tiên, tác phẩm tập trung vào bàn thờ, một vật cố định phổ biến trong hầu hết các hộ gia đình Việt Nam. Bàn thờ là nơi diễn ra các hoạt động gia đình cũng như là không gian linh thiêng để tưởng nhớ những người đã khuất. Bàn thờ được sắp xếp tỉ mỉ, thường trưng ảnh của người đã khuất, cùng với các lễ vật cúng như bia, trái cây và hương. Phạm nói về mối quan hệ qua lại giữa người chết và người sống vượt thời gian này, “những bàn thờ này đóng vai trò như một sợi dây liên kết hữu hình với tổ tiên của chúng ta. Các nghi lễ hàng ngày, ví dụ là việc thắp hương, đóng vai trò như lời nhắc nhở sâu sắc về bản chất phù du của cuộc sống.” Những chiếc đèn lồng lớn hơn người thật mô phỏng ánh sáng dịu nhẹ thường đi kèm với bàn thờ tổ tiên. Tác phẩm vừa là sự dâng hiến lòng biết ơn đối với tổ tiên của Phạm vừa là biểu hiện vật chất của sự ngọt ngào và kiên trì mà phước lành của tổ tiên đã mang lại. Bởi vì lịch sử luôn được tôn vinh, người chết vẫn tiếp tục sống và tồn tại vượt ra ngoài ranh giới của cuộc sống, vì được tưởng nhớ là một cách để tái sinh. Mặc dù trái cây có thể hư hỏng, lịch sử sẽ tiếp tục chảy qua các mạch máu của người sống, như Phạm tuyên bố, “Cuộc sống mà tôi đang sống bây giờ, cuộc sống tự hiện thực hóa, là nợ cha mẹ, ông bà và tổ tiên của tôi, những người chỉ có lựa chọn là sống sót và đóng góp cho một cuộc sống tốt đẹp hơn cho các thế hệ tương lai.”

Click to enlarge

Kimberly Ha

A Family Affair

2022

Archival pigment print

14 x 11 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Kimberly Ha (b. 1989) was born in Houston, Texas but raised in New Orleans, Louisiana. As a young creative, Ha was drawn to streetwear and graffiti art, influenced by The B-Boys, K-Pop and Japanese Rock. Soon afterward, she became enthralled with the luxurious world of Haute-Couture magazines and catalogues. Specifically, a fascination with the photoshoot sets of avant-garde fashion houses, such as the pioneering and gender blurring visions of Yves Saint Laurent, who did not shy away from showcasing women in menswear. Though high fashion was the initial inspiration for her most recent body of work, Full Set, the series slowly evolved beyond the lens of fashion and transitioned into a love letter to her mother, Calinh Do — and by extension, the strength and confidence of women and femmes of color. Her mother’s nail salon was the formative backdrop of her childhood and became a significant source of material for Full Set. Vietnamese women, like Ha’s mother, transformed the nail salon industry into what it is today. Following the war, many turned to the nail salon industry to support their families — a path partly inspired by actress and activist Tippi Hedren in 1975, who introduced Hollywood-style nail care to refugee women. However, in just a few decades, the industry grew to be worth over $8 billion. In this series, Ha combines intimate memories with 21st century nail design, visually evident on each carefully curated set of nails – leading craft into the realm of fine art through artistry and aesthetic vision. Though Ha is at the helm of the creative process behind Full Set, she is at heart an avid collaborator – working closely with makeup and nail artists Katalina Mitchell, Nails by Lorsace, Amanda Lee Harvey and Jane Chaisson.

Throughout this body of work, Ha embellishes the compositions with ornate detail, as seen in the lavish spread of A Family Affair. In this image, Ha depicts a game of bầu cua cá cọp (gourd crab fish tiger), typically played during Lunar New Year, and the jade-adorned hands of notable New Orleans chef and author, Nini Nguyễn. Furthermore, a number of works from Full Set allude to a sense of youthful nostalgia, such as Empress 1 and Empress 2. These two works reference the martial arts films of Ha’s childhood and her recollection of seeing “the first image of a powerful woman on the TV screen.” These movies defied the gender archetype for Asian women in film by exuding agency and strength of character, portrayals rare within Western media. In Jackie, however, Ha reveals a more introspective and vulnerable nature to women’s perseverance. In this work, she channels her own mother through Jackie Kennedy – both women shaped by hardship – taking inspiration from the 2016 film of the same title, Jackie. The lotus flower in the upper left corner is a nod to her mother’s love of gardening, her place of refuge. Ha writes, “The inspiration that came from Jackie (film) was watching a woman truly be resilient after such a traumatic experience. It reminded me of my mother, who pushed through all of her traumatic experiences and provided a life for her children.”

Click to enlarge

Lien Truong

That Mimetic Waltz of the Moirai

2018

Oil, silk, acrylic, antique 24k gold-leaf obi thread, embroidery by Vu Van Gioi,

Linen on canvas

96 x 72 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Quynh

That Mimetic Waltz of the Moirai is one of five large scale paintings in Truong’s Mutiny in the Garden series, which examine the political conditions embodied in America’s founding agrarian philosophy. The works reimagine themes in Thomas Cole’s Course of Empire, a series of allegorical paintings that explored the rise and fall of empire through the aesthetic of Romanticism. Cole’s “Consummation of Empire,” is one of the paintings in his series, depicting empire in its glory. Cole was against American imperialism, and saw his series of paintings as a moralistic narrative, stated the painting showed “…a triumphal fete would indicate, man has conquered man — nations have been subjugated.”

That Mimetic Waltz of the Moirai rejects the romanticized illusions of early American landscape paintings. Truong creates a narrative space as a frenetic amalgamation, composing landscape and modes of storytelling that include historic and contemporary experiences. The title adopts the Greek Destinies for context, citing the prominence proclamations of destiny have had in supporting ideologies of supremacy to justify global colonialism. On the bottom left of the work, she paints a faded image of Castillo San Felipe del Morro, a fort in Puerto Rico built by Spain in the 16th century. Spain ultimately ceded ownership of the territory, along with Cuba and Guam to the United States during the Spanish American War under the Treaty of Paris.

Physical painted textile and historic textile designs refers to the historic textile grade, a centuries old narrative of migration and power. In the center right, Truong has painted a swatch of the green velvet curtain dress from Gone With the Wind whose cloth symbolized a mythological act of feminine rebellion, within a film long embedded in the American psyche that is white and privileged. A plethora of painted textile designs reference the 16th to 20th centuries from Turkey, Mexico and Spain.

In homage of Cole’s grand narrative, Truong depicts a multitude of characters and symbols painted on silk: monuments of Andrew Jackson and Ulysses S. Grant, white precious bundles representing migrant children in silver blankets, separated from their parents and in detention camps, and kkk figures. On the upper left on silk, is a fractured portrait of Joaquin Murrieta Carillo: a 19th century Mexican gold miner in CA, believed to have inspired the fictional character of Zorro. Though evidence is limited, Murrieta has become a legendary outlaw, adopted by activists in the 20th and 21st centuries as a symbol of resistance and hope in CA, on land occupied by indigenous tribes and independent Mexicans before it was colonized.

Click to enlarge

Millian Pham

Buffalo Bum: Cycle Breaker

2022

Acrylic paint and bead embroidery

38 x 19 Inches

Courtesy of the artist

Millian Pham Lien Giang (goes by Millian or Giang) received her MFA from the University of Florida and BFA from The University of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Pham’s visual investigations are rooted in her traumatic experience from living in post-war Vietnam and later in U.S. poverty. Each work experiments with the aesthetic codes and conceptual framework of multiple cultures, art mediums, and languages. Pham’s art practice includes installations of still and moving images, crafted and found objects, and performance (as event and experience). She currently practices and teaches art in Alabama.

Millian Pham Lien Giang (gọi là Millian hoặc Giang) đã nhận bằng MFA từ Đại học Florida và bằng BFA từ Đại học Tulsa, Oklahoma. Các cuộc điều tra thị giác của Pham bắt nguồn từ trải nghiệm đau thương của cô khi sống ở Việt Nam sau chiến tranh và sau đó là trong cảnh nghèo đói ở Hoa Kỳ. Mỗi tác phẩm đều thử nghiệm với các quy tắc thẩm mỹ và khuôn khổ khái niệm của nhiều nền văn hóa, phương tiện nghệ thuật và ngôn ngữ. Hoạt động nghệ thuật của Pham bao gồm các tác phẩm sắp đặt hình ảnh tĩnh và chuyển động, các vật thể thủ công và tìm thấy, và trình diễn (như sự kiện và trải nghiệm). Hiện cô đang thực hành và giảng dạy nghệ thuật tại Alabama.

Buffalo Bum: Cycle Breaker

Pham’s series Viet Kitsch: Lacquer Luster puts a twist on a traditional Vietnamese art form. Lacquer painting is a technique that Vietnam is famous for, with its specialized wooden canvases and glistening sheen often derived from mother-of-pearls or eggshell materials. For Pham, whose practice concerns a critical obfuscation that fights legibility, texts and images often juxtaposed one another to question the pre-established conventions of fine art.

Buffalo Bum in particular is a cheeky reference to the Vietnamese slang ‘Trẻ trâu’, often referring to the rebellious youth with an oversized ego. In this context, it can also refer to someone that sits around all day with nothing pressing or urgent to attend to. Pham cites communicative discrepancy between her and her parents, both linguistically and ideologically, to be one of the inspirations behind the piece. “Romanticized images of rural living are mixed with texts that question traditional notions of gender, class, and culture,” she writes. Following the war, many Vietnamese families in America found themselves hustling to assimilate, both financially and socially. The effects of this hard work often manifests through tense conversations with their children and high expectations that cause a rift in familial relationships. With the piece aptly titled Buffalo Bum: Cycle Breaker, perhaps Pham is leading the viewer towards a space where relaxation and slowness is key, and the cycle of toxic expectations can be broken after all.

Bộ tác phẩm Viet Kitsch: Lacquer Luster của Pham đã làm thay đổi một hình thức nghệ thuật truyền thống của Việt Nam. Tranh sơn mài là một kỹ thuật mà Việt Nam nổi tiếng, với những tấm vải gỗ chuyên dụng và lớp sơn bóng lấp lánh thường có nguồn gốc từ xà cừ hoặc vật liệu vỏ trứng. Đối với Pham, người có phương pháp thực hành liên quan đến sự che giấu quan trọng chống lại khả năng đọc, các văn bản và hình ảnh thường được đặt cạnh nhau để đặt câu hỏi về các quy ước đã được thiết lập trước của mỹ thuật. Buffalo Bum nói riêng là một tham chiếu táo bạo đến tiếng lóng của Việt Nam là ‘Trẻ trâu’, thường ám chỉ những thanh niên nổi loạn có cái tôi quá lớn. Trong bối cảnh này, nó cũng có thể ám chỉ một người ngồi quanh cả ngày mà không có việc gì cấp bách hay khẩn cấp để quan tâm. Pham trích dẫn sự khác biệt trong giao tiếp giữa cô và cha mẹ, cả về mặt ngôn ngữ và ý thức hệ, là một trong những nguồn cảm hứng đằng sau tác phẩm. Cô viết: “Những hình ảnh lãng mạn về cuộc sống nông thôn được pha trộn với các văn bản đặt câu hỏi về các khái niệm truyền thống về giới tính, giai cấp và văn hóa”. Sau chiến tranh, nhiều gia đình người Việt ở Mỹ thấy mình phải vật lộn để hòa nhập, cả về mặt tài chính lẫn xã hội. Hậu quả của công việc khó khăn này thường biểu hiện qua những cuộc trò chuyện căng thẳng với con cái và kỳ vọng cao gây ra rạn nứt trong các mối quan hệ gia đình. Với tác phẩm có tựa đề chính xác là Buffalo Bum: Cycle Breaker, có lẽ Pham đang dẫn dắt người xem đến một không gian mà sự thư giãn và chậm rãi là chìa khóa, và chu kỳ kỳ vọng độc hại cuối cùng cũng có thể bị phá vỡ.

Click to enlarge

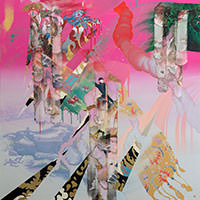

Brandon Tho Harris

Visions of Tomorrow

2019

Mixed media installation

Dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artist

Brandon Tho Harris (b.1995, Houston, Texas) is an interdisciplinary artist and arts professional based in Brooklyn, New York. His creative practice explores his identity as a child of war refugees. Through intensive research on the Vietnamese diaspora in relation to his family history, he examines notions of intergenerational trauma, displacement, and the land as a living archive. Found in his work are often self-portraiture, his family archives, found objects, raw materials, and historical images portraying the Vietnam war. Through the use of photography, video, performance, and installation, he provides viewers with a deeper understanding of the complexities surrounding migration.

Brandon Tho Harris (sinh năm 1995, Houston, Texas) là một nghệ sĩ đa ngành đang sinh sống và làm việc tại Brooklyn, New York. Quá trình sáng tạo của anh dò xét lịch sử của bản thân với tư cách là hậu duệ của người tị nạn chiến tranh. Qua quy trình nghiên cứu chuyên sâu về cộng đồng người Việt di cư liên quan đến lịch sử gia đình, Harris xem xét các khái niệm về chấn thương liên thế hệ, sự trục xuất, và vùng đất như một kho lưu trữ sống. Trong tác phẩm của anh thường có chân dung tự họa, tài liệu lưu trữ của gia đình, vật thể tìm thấy, nguyên liệu thô, và hình ảnh lịch sử mô tả chiến tranh Việt Nam. Thông qua phương pháp nhiếp ảnh, video, trình diễn, và sắp đặt, anh cung cấp cho người xem sự hiểu biết sâu sắc hơn về sự phức tạp xung quanh vấn đề di cư.

In this ambitious collage, Harris unpacks a history both familiar to him through passed down memories of family and unfamiliar to him through American media representations. He inquires the nature of ‘iconic’ war images, positing that what often makes them iconic is the very suffering and helplessness of the Vietnamese personhood at the center of the representation. Much of art is tasked with remembrance, but whose memories are being consumed?

Harris set out to combat this mystification of war and of Vietnamese personhood by incorporating markers of individuality – photos from family archives, a birth certificate, his grandparents’ wedding plaque postulate a dimensional Vietnamese identity, one that is much more textured and layered than any ‘iconic’ image of war can communicate. Harris’ image manipulation is colored with personal history – a postcard featuring a hand with extraordinarily long nails was colorized and embellished by the artists to represent the line of work popular among Vietnamese immigrant communities, even in Harris’ own family. The artist also highlights pivotal moments in Vietnamese-American history by including an image of the Ku Klux Klan boat burning in Galveston, Texas. After years of dangerous harassment from the KKK over shrimping territories, including ceremonial boat burnings, the Vietnamese Fisherman’s Association filed a federal lawsuit against the Ku Klux Klan with the help of the Southern Poverty Law Center. The 1981 lawsuit Vietnamese Fishermen’s Association v. Knights of the Ku Klux Klan became a landmark case, leading to the ultimate disbandment of their paramilitary militia and activities.

In this work, Harris reconciles the disconnect often experienced through digital witnessing and invites the viewers to think about what it means to consume memories from a detached distance. Harris contextualizes the war with personal details of its participants in an effort to remove the ‘iconic’ image curse that often plagues Vietnamese war representations. The artist colors the gaps of memories for viewers, while investigating a history that is simultaneously public and private.

Trong tác phẩm ghép đầy tham vọng này, Harris giải nén/tháo gỡ một lịch sử vừa quen thuộc với anh qua những ký ức được truyền lại về gia đình và vừa xa lạ với anh qua các phương tiện truyền thông Mỹ. Anh tìm hiểu bản chất của những hình ảnh chiến tranh mang tính biểu tượng, đưa ra giả thuyết rằng điều thường khiến chúng trở nên mang tính biểu tượng chính là nỗi đau khổ và sự bất lực của nhân cách người Việt Nam ở trung tâm của sự thể hiện. Phần lớn nghệ thuật được giao nhiệm vụ tưởng nhớ, nhưng ký ức của ai?

Harris bắt đầu chống lại sự huyền bí hóa này về chiến tranh và nhân cách người Việt Nam bằng cách kết hợp các dấu hiệu của cá tính – ảnh từ kho lưu trữ gia đình, giấy khai sinh, tấm bảng kỷ niệm ngày cưới của ông bà anh đưa ra giả thuyết về một bản sắc Việt Nam đa chiều, một bản sắc có nhiều kết cấu và lớp