“Read the first page of Many Minds, One Heart,” Larry Goodwyn said. It was the last time I saw the Duke University historian, at his home in Durham six months before his death in September 2013. Goodwyn, best known for his defining work on American populism, almost recited the first paragraph of Wesley Hogan’s history of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

It’s August 1962 and a 21-year-old Charles McLaurin, “knees shaking, mouth closed tightly, so as not to let them hear the fear in my voice,” is driving three elderly black women to the Sunflower County Courthouse in Indianola, Mississippi. They were practiced and prepared to face down a county court clerk and say, “I want to vote.” Then ask for their registration forms.

As it turned out, I knew McLaurin. At 7 a.m. on Election Day 2008, I was standing in a long, serpentine line outside the Bethune Community Center in Indianola, Mississippi, waiting for him to go inside and cast his vote. I had made the trip to see a circle closed, to witness the moment when one of the men (there were also many women) who had put their lives on the line to restore a constitutional right denied since Reconstruction cast his vote for an African-American president.

McLaurin had been jailed 35 times, “badly beaten only once,” he told me in a 2003 interview, when he also described his encounter with authority at the Indianola courthouse in 1962. The three women trying to register to vote that summer day (“Augusta Hicks for the 20th time”) were met by a court clerk who asked “What you niggers want?” then turned them away. McLaurin would spend the next four years registering voters in the Mississippi Delta—at considerable personal risk.

For Charles McLaurin, voting for Barack Obama was the fulfillment of a dream deferred. After casting his vote, he stepped out into the soft light of a cool Delta morning, raised his hands toward the sky, and said: “This is a jubilee day!”

A very old man, disappearing into a Sunday-morning suit that might have fit him 10 years earlier, lifted up his cane and echoed McLaurin.

“Mister, this is a hallelujah day!”

If there was time and place where you could know in your bones that this is not just a great country but also a good country, it was November 8, 2008, in Sunflower County, Mississippi.

The three women trying to register to vote that summer day were met by a court clerk who asked “What you niggers want?” then turned them away.

C.C. Campbell, the circuit court clerk who denied three elderly black women access to a right enshrined in the Constitution, is a footnote in the history of the Jim Crow South. He was an elected official doing what was expected of him in a system that, as Ta-Nehisi Coates writes in Between the World and Me, presumes it can correctly organize a society based on “difference in hue and hair.” A foot soldier on the wrong side of history.

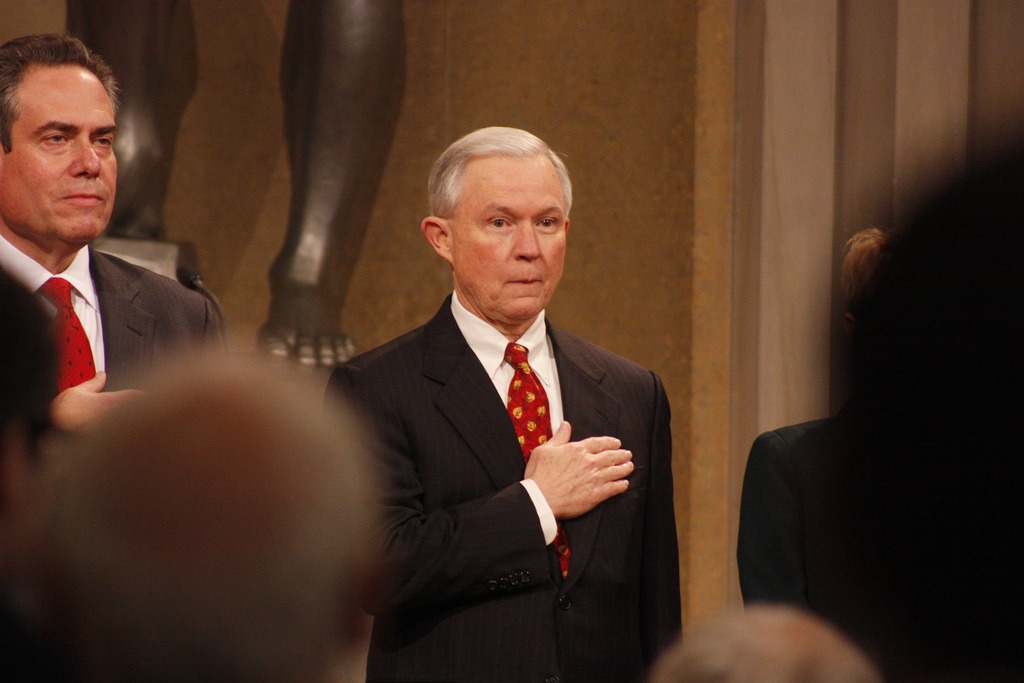

Jeff Sessions was a field officer in that same struggle, also on the wrong side of history. That’s why so many African-American critics of Sessions’s appointment to lead the Department of Justice tried to focus the Senate Judiciary Committee on one critical moment in his career as a U.S. Attorney, which came to light when Ronald Reagan nominated him to serve as a district court judge in 1986.

You can learn a lot about Jeff Sessions from the 585-page transcript of his 1986 confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee. As a young U.S. Attorney angling for a lifetime appointment to the federal bench, Sessions was less than lawyerly, and often equivocating, in his responses to questions about his record.

To the best of his recollection he might have told a black Assistant U.S. Attorney on his staff: “You ought to be careful as to what you say to white folks.” But there was context to consider; the attorney, Thomas Figures, had made a “cutting remark” to a white secretary. And as Sessions recalled it, he might have said “folks,” not “white folks.”

Regarding the comment —“You know the NAACP hates white people; they are out to get them. That is why they bring these lawsuits, and they are a commie group and a pinko organization”—if Sessions actually said it, it was because “I am loose with my tongue on occasion, and I may have said something similar to that. . . .”

Regarding his comment to Figures about the Ku Klux Klan during a trial of a Klansman indicted for lynching a black man—“Those bastards; I used to think they were O.K., but they are pot smokers”—what he said was so outrageous that it was “ludicrous that anybody would think that it was supporting the Klan.”

Or regarding a Justice Department lawyer who testified that he’d heard Sessions refer to a white civil rights attorney as a “disgrace to his race,” Sessions kind of recalled a conversation in which: “I have heard him referred to as a disgrace to his race.” And perhaps he simply repeated it.

There was more. Figures testified that Sessions had called him “boy,” which Sessions denied, while another white staff attorney described Figures as “racially sensitive” and “a good attorney with a bad attitude.” Sessions observed that he could not understand why Figures had cut off communication with the office after he resigned.

Over the course of a four-day hearing, there was a lot of testimony that characterized Sessions as racially insensitive, at best. Guilty of using the everyday remarks that whites used (and continue to use: read Claudia Rankine’s Citizen) to remind African-Americans of their place in a hierarchy defined by hue and hair.

But none of it was on the public record, so these claims, although offered under oath, were not enough to persuade a bipartisan majority of a committee chaired by unabashed segregationist Strom Thurmond to block an appointment to the federal bench—which is exactly what the Senate Judiciary Committee did.

It was Sessions’s selective prosecution of three African-Americans who had conducted a voter-turnout campaign in Perry County, Alabama, that denied Sessions a lifetime appointment as a federal judge.

In what must have seemed an interminable hearing (especially to Sessions), Delaware Senator Joe Biden led scores of witnesses, including Sessions himself, through testimony that established that as U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Alabama, Sessions’s prosecution of a legendary Alabama civil rights leader on claims that he’d tampered with 29 absentee votes cast in a local election was influenced by race and was without merit.

In March 1965, Albert Turner was walking behind SNCC leader John Lewis as he led a voting-rights protest march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, a peaceful demonstration that club-wielding state troopers turned into “Bloody Sunday.” In April 1968, Turner was leading the mule cart carrying Martin Luther King’s casket through the streets of Atlanta.

In 1985, Turner, his wife Evelyn, and civil rights leader Spencer Houge were in a federal courtroom in Selma, confronting 29 counts, for mail fraud and altering absentee ballots—a criminal prosecution led by U.S. Attorney Sessions that could have sent the defendants to a federal penitentiary for a maximum sentence of 100 years.

Turner, who had also worked with King at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was known as “Mr. Voter Registration,” for the successful registration and turnout campaigns he had led in Alabama’s “black belt.”

Sessions broke new ground in filing the case. He was the first U.S. Attorney to use the federal voter fraud statute:

To prosecute a defendant who was not a corrupt public official; in a criminal prosecution that involved only local officials; in a prosecution based on so few allegedly illegal votes; in a criminal cause of action in which the candidates who allegedly benefited from the fraud had lost, rather than won, the election.

It took a jury of seven blacks and five whites less than three hours to find the defendants not guilty on all counts.

As it turned out, Sessions had “selectively” (as Joe Biden pointed out) prosecuted Houge and the Turners on threadbare evidence, after ignoring complaints filed in his office that described a batch of absentee ballots collected at an assisted-living residence which had been completed with the same felt-tip pen, and signed, according to a handwriting analyst, by the white Republican mayor of Uniontown, Alabama. Those ballots were certified by the Perry County Clerk, who appeared to be running her voting scam: simultaneously mailing campaign literature from candidates supported by the white community along with absentee ballots, sometimes even tucking campaign flyers into envelopes with the ballots, which was also reported to Sessions.

Two white public officials who appeared to be rigging elections in violation of state and federal law got a pass, while Sessions tried to put the Turners and Spencer Houge in prison for 100 years—for what a jury unanimously decided were acceptable errors in 29 of 500 absentee votes the defendants gathered and mailed in.

The symbolism of three African-American defendants on trial in Selma was not lost to Alabama’s black community. And the prosecution was using the same old hustle black voters in the South had seen for decades, but with more refined tactics. If Sessions wasn’t as rankly racist as Indianola Court Clerk C.C. Campbell, he was discouraging black voters from exercising a right enshrined in the Constitution (even if it required a war, two amendments, and the courage of thousands of voting rights activists, from Charles McLaurin to Albert Turner, to secure that right for African-Americans in the South).

Turner’s son, a county commissioner in Alabama, has worked with Sessions and has forgiven him for the prosecution of his parents 32 years ago.

Evelyn Turner hasn’t.

“Get off me,” she told Sessions when he tried to hug her at the 50th anniversary of the Bloody Sunday march.

“He hasn’t changed,” she said.

0 Comments