Day by day, unsealed document by unsealed document, the American people are learning in this summer of discontent a great deal about the values and vision of Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, a judge of relentless conservative mien who, if confirmed, will push the Court as far right as it has been in nearly a century. Given his long record of contentious public service on and off the federal bench, Kavanaugh may be the most thoroughly documented nominee in the history of the Court and one of the most controversial, too, which is why Republicans have been so keen to get him to his Senate Judiciary Committee hearing as soon as possible.

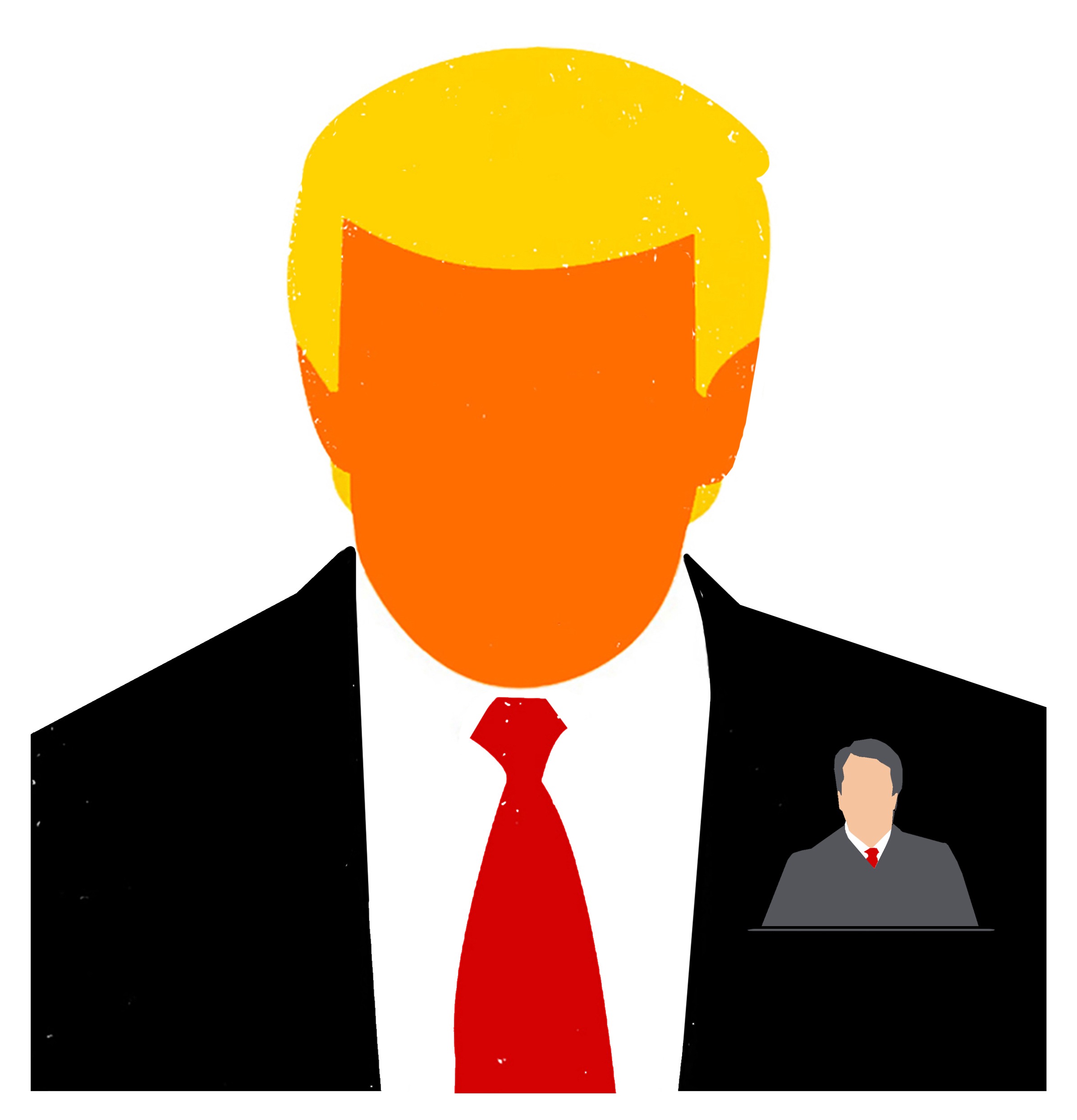

We already can predict from his past rulings as a judge in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, and from his loyal work for the Bush administration, that Kavanaugh as a justice will do great harm to the rights of women, the health of the planet, and the economic welfare of workers. But none of the garden-variety ways in which he’ll do the Federalist Society’s bidding on the Court makes his nomination the most important of our lifetime. What qualifies him for that distinction is the fact that, if confirmed, Justice Kavanaugh, before the end of the year, could cast a deciding vote in a case involving a direct challenge to the power of the dubious president who nominated him.

If there were any reason to think that Brett Kavanaugh had the political inclination or judicial countenance to exercise independence when the inevitable Mueller v. Trump showdown occurs, the nation might well rest easy. Judicial independence and checks on executive power should be bipartisan goals. But there is absolutely no reason to think Kavanaugh would vote to check Trump’s coming assertion of presidential authority. Virtually every public sign so far tells us the opposite is far more likely: that Kavanaugh will gleefully endorse the idea of sweeping presidential powers during Republican administrations and sweeping restrictions on executive action during Democratic ones. To paraphrase Chief Justice John Roberts, Kavanaugh will be the umpire who calls only strikes for the home team and only balls for the visitors.

We now know that Kavanaugh once mused about the power of a president to pack the court. We now know that he once suggested that the Supreme Court’s seminal ruling against President Richard Nixon, requiring the White House to turn over the president’s tapes, may have been wrongly decided. We even know now that he didn’t think much of the independent counsel statute, now gone—a position that helps us get a clear sense of where Kavanaugh would land in a clash between the White House and the special counsel, Robert Mueller.

On and on the revelations have surfaced, each detail contributing to the rich picture of a die-hard Republican operative who, like Roberts, blended legal intellect with political acumen to reach this moment. But Kavanaugh is more conservative than Roberts—which is saying something—and he comes before the Senate at a moment of partisan fervor that did not exist when Roberts was confirmed, during the second Bush era. This contrast helps explain the dissonance in the messages about his nomination. Trumpites are reassured that Kavanaugh is their kind of guy, while senators and mainstream reporters are being reassured that he’s an institutionalist.

This is true also of the roiling fight over abortion rights that has animated much of the speculation, and it’s true of the argument over Kavanaugh’s positions on gun rights and the Second Amendment. The nominee isn’t going to say anything of substance about these topics during the public portion of the confirmation hearing, and it’s hard to imagine him being particularly candid during the closed meetings senators have with the nominee. Every sentient senator should know by now who he is and what they’ll be voting for if they vote for him.

The Republicans today have the votes, and they know it, but here’s where it gets tricky. The whole dynamic of this nomination could change over how the timing of the confirmation hearing and the subsequent vote will play out amid the backdrop of the Mueller investigation into Team Trump’s Russia ties. A Judiciary Committee confirmation hearing that takes place a week or so after the next set of federal indictments are handed up against more of the president’s men would have a very different political feel from one that comes a week or so before those indictments.

The conflict that Kavanaugh and Trump have is an inherent one. Every judicial nominee, on some level, could be said to owe something to the president who nominates him (and with Trump and judicial nominees it’s almost always a white, conservative “him”). But no nominee in our age would so quickly be forced to decide the fate of his benefactor as would Justice Kavanaugh if the White House were to challenge a Mueller subpoena or a request for a presidential deposition, or if it were otherwise to assert “executive privilege” to try to thwart the aims of the special counsel’s work. And the thing is, Mueller himself largely will determine whether Kavanaugh’s conflict moves from the hypothetical to the practical.

Kavanaugh may have the votes today, barely, but he also faces political headwinds his predecessor, Neil Gorsuch, avoided. Not just because the Mueller investigation has been more visibly productive in 2018 than it was last year, but because Gorsuch’s arch-conservative votes this past term—on unions and the travel ban and voting rights—are vivid reminders of how much less moderate he is than advertised. Nor did Gorsuch have the long written record, qua baggage, that Kavanaugh must lug with him onto Capitol Hill. And on the substance of their jurisprudence, the Scalia-Gorsuch trade-off is nowhere near as disastrous to liberals as a Kennedy-Kavanaugh trade-off will be. Which explains why the ferocity of the opposition, this time out, is so much more intense.

There is a reason Senator Mitch McConnell warned against Kavanaugh as a candidate. There is a reason the Republicans are racing to get the hearing over with. Each day it lags without a vote is a day when the special counsel could strike and interrupt the White House’s grand plan. The Kavanaugh nomination also reminds Democratic voters of the importance of elections on the eve of one of the most momentous midterms in memory. The roots of the reason Neil Gorsuch is on the Court and Brett Kavanaugh is on his way, why abortion rights are imperiled and Donald Trump may skate, go back to the last midterm, in 2014, when laconic Democrats stayed away in droves from the ballot box and allowed Republicans to retake the Senate.

Kavanaugh was a predictable nominee for this president. The Republican embrace of the nominee has been predictable, too, right down to the shameless way in which McConnell accused Democrats of trying the very tactics he employed successfully to block the nomination of Merrick Garland in 2016. What we don’t know is whether Senate confirmation of Kavanaugh helps fuel a Democratic wave in Congress in November, or whether a Mueller indictment jeopardizes Kavanaugh’s confirmation before the election. That’s why tens of millions of dollars in advertisements one way or the other will be spent between now and the Senate vote—even though it feels, amid the claims and counterclaims, like we all are in the same driverless car hurtling toward the cliff.

Andrew Cohen is a senior editor at the Marshall Project and a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice.

0 Comments