America has become obsessed with feeling insecure. It has become an endemic part of the culture, though it wasn’t always this way. I am old enough to remember as a child, at the movies, we would watch the ads before the film started. One of them would always be for Marlboro cigarettes. It was always the same one, featuring the “Marlboro Man.” He was a cowboy. The setting was remote, far out on the range as he herded cattle. He was rugged, independent, and implicitly fearless. He lived on the frontier—geographically and psychologically. We marveled at his forthright existence—and bought Marlboro cigarettes, even as we lived in the rather more urbane setting of Central London.

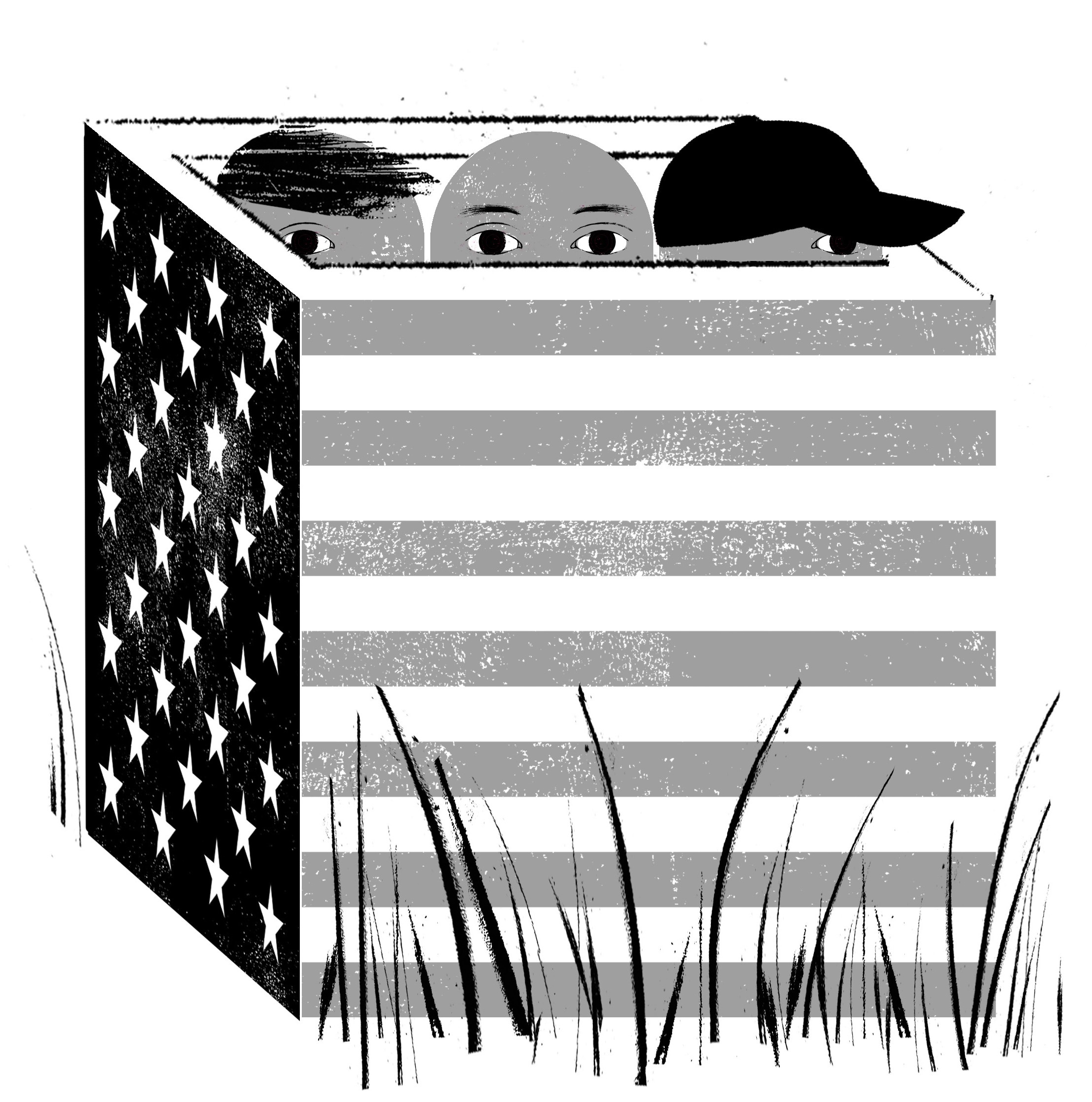

That emblematic figure has gone the way of ads for cigarettes and, for the most part, cowboy movies. America’s self-image has changed, even if we don’t necessarily acknowledge it and still tap into that old part of the culture. Two-thirds of us bought cars and trucks that are designed for traversing the frontier last year—and most of us then drove them through nothing more challenging than suburban neighborhoods. In contrast, “See something, say something” has become an iconic phrase in the first two decades of the 21st century. It may be a sensible invocation, but it is also a reflection of our new guardedness.

The shifting of our fears from national to human security

Until the 1990s, traditional conceptions of security—conventional and nuclear war—dominated the policy agenda. But in 1994, the United Nations issued a Human Development Report that introduced the idea of human security. The report’s authors noted that:

The concept of security has for too long been interpreted narrowly: as security of territory from external aggression, or as protection of national interests in foreign policy or as global security from the threat of a nuclear holocaust. It has been related more to nation-states than to people…. Forgotten were the legitimate concerns of ordinary people who sought security in their daily lives. For many of them, security symbolized protection from the threat of disease, hunger, unemployment, crime, social conflict, political repression, and environmental hazards.

The report kicked off a policy agenda that evolved into the U.N.’s Millennium Goals.

I explain to my students that national security is concerned with the kinds of historic threats that killed millions of people in the two world wars—and potentially could do so again. But human security is concerned with the things that kill people today—crime, poverty, civil war, and disease.

American policymakers initially scoffed at the human security agenda. They liked and supported the rule of law dimension—democracy promotion and the growth of civil society—especially under Bill Clinton. But they eschewed using the term “human security.” Many saw it as a thinly veiled effort by the U.N. and the global south to redistribute wealth from rich, industrialized states, particularly the United States, through an assortment of health and welfare programs and reparations for historical and imperialist misdeeds, such as slavery. And, in perhaps more paranoid circles, they viewed it as a backdoor way to reintroduce a Marxism agenda after the fall of Communism. For them, the U.N.’s leadership was an accomplice. This view was epitomized by John Bolton when, as the U.S. ambassador to the U.N., he objected even to the mention of the Millennium Development Goals.

Yet, bearing in mind the antipathy of policymakers, it is fascinating to discover how much Americans have assimilated elements of the human security agenda into their own thinking. The findings of a 2017 Chapman University survey titled “America’s Top Fears” are revealing. The corrupt behavior of government officials topped the list at 74.5 percent, followed by the consequences of Trumpcare; the pollution of varied natural resources that Americans use, such as rivers and streams; economic insecurity; and rising medical costs. These findings largely track the priorities laid out in that 1994 U.N. report and illustrate that when it comes to their major fears, Americans—consistent with the logic of human security—focus most on the things that will most likely harm them personally.

What is not ranked in the top five of the Chapman survey is just as revealing. Terrorism became the third leg of the national security agenda after 9/11. In wave after wave of opinion polls since then, Americans have rated it at or near the top of their list of “critical threats to U.S. vital interests.” Most recently, 17 years after 9/11, in a Gallup poll on conventional national security issues, 75 percent of respondents still saw terrorism as a critical threat, superseded only by two more topical issues: North Korean nuclear weapons and disruptive cyberattacks.

These views are widely reported in the media. Yet they need some perspective. In the Chapman survey, the fear of a terrorist attack ranked only 13th. Though the survey was conducted in the midst of the North Korean crisis, the prospect of the United States being involved in another world war only ranked seventh. And the consequences of global climate change only ranked eight, despite the floods, fires, and storms that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates cost the United States $306 billion last year and killed 362 people.

How to interpret these rankings? National security polls like the Gallup one focus mainly on existential threats, on things that may often seem remote to the average person. North Korea poses a missile threat, but the range of the delivery vehicles at the moment is unclear, and as President Trump has bluntly stated, the United States has a deterrent—a bigger and better bomb. Terrorism may pose a threat, but it feels as though it is a nominal one if you live outside the Boston–Washington corridor. Climate change in the long run is probably our greatest challenge, although it is an abstraction compared to the need for gas to get to work. But job insecurity? Now that is a threat that the average American lives with every day.

So, despite the media hype about terror attacks, wars, natural disasters, and mass shootings, the respondents’ fears in late 2017 were clearly focused on the things that they think will harm them personally. They haven’t forgotten about the national security threats. But things have clearly changed. Americans have both reordered and expanded their concerns.

Explaining the change

Americans regard 9/11 as a historical turning point, like the American Revolution, the Civil War, and the Great Depression. George W. Bush may have used defiant language as he stood atop a smoldering Ground Zero, but the events of 9/11 clearly punctured a collective sense of American invulnerability. And the subsequent failure to conquer, quell, and then democratize both Afghanistan and Iraq demolished a still-lingering belief in the unassailable capacity of America’s military forces to accomplish any task put before them.

Something consequentially changed in the American psyche. Apprehension replaced what William Fulbright, over five decades ago, called “the arrogance of power.” Americans started to debate—and advocate—constructing walls, physical and psychological, rather than building bridges. Government priorities shifted in response to the public’s clamor for the need to feel more secure. The Bush administration reacted by creating the Department of Homeland Security, the military budget that had declined during the Clinton presidency now ballooned, and federal spending priorities shifted. Americans couldn’t get enough “security,” and they were willing to pay for it, in the belief that government could make them more secure and, just as importantly, make them feel more secure.

The growth of the DHS illustrates this point. Funding for homeland security rose from $16 billion in 2001 to just under $65 billion in 2016, Obama’s last year in office. This shift is most conspicuously symbolized by the politics of the Southern border. George W. Bush and Barack Obama increased the federal government’s budget for Customs and Border Protection by 91 percent between 2003 and 2014, from $6.6 billion to $12.4 billion. The number of (land-based) border agents over that decade almost doubled, from 10,717 to 21,391. Both presidents called up reservists to supplement border security. Bush began building up to 700 miles of border wall under the Secure Defense Act of 2006. Obama completed the job and deported 5.28 million people, according to the Migration Policy Institute. As far as we know, nobody who ever committed a terrorist act ever entered the United States through the Southern border, and all these new measures have failed to interrupt the flow of undocumented migrants—but still, Americans who yearn to feel more secure have remained convinced that enhanced border security is a large part of the solution.

Donald Trump, recognizing that Bush’s and Obama’s measures have had a limited effect on insulating the Southern border, therefore rails against his predecessors’ policies. He offers his electoral base the promise that he will do more—and do it better. He promises them a “big, beautiful wall” and more custom and border agents, supplemented by the National Guard. But his demands and initiatives to date—more border security, more apprehensions and deportations—only maintain or extend the policies of his predecessors. The rhetoric is much harsher and the implementation of policy more brutal—with stepped-up Immigration and Customs Enforcement interventions around the country and the separation of children from their families at the border—but the trajectory is familiar. And the outcome will be the same: desperate people will keep arriving. They will risk their lives crossing the desert. And the notion of increased vulnerability—from Mexican rapists, criminal gangs, and undocumented migrants taking jobs—will continue to be served up by Trump at the altar of electoral politics, evocative of the politics of fear.

The things that Americans worry about have therefore expanded to include both national security and human security issues. This has created an irreconcilable tension: between their sense of vulnerability, what they regard as realistic threats, and their demand for security. Many Americans now reside in a permanent state of anxiety, having developed a “zero tolerance” when it comes to their fears. Stress has effectively become a major 21st-century disease, according to the American Psychological Association, with the primary symptoms, according to a Harris poll, being anxiety, anger, and fatigue.

Voters now want government to provide blanket protection from all of those vulnerabilities. The result is simply too much demand on the public process and purse. Inevitably, governments have to, and do, make choices about which threats to prioritize, often with brutal consequences. There is, of course, domestic protest in response to such measures. But many fearful Americans have accepted and normalized them in the search for greater security.

Differing assessments

Government documents often reflect cultural and psychological shifts. Every administration is mandated by law, for example, to produce a National Security Strategy. This report outlines a president’s view of the major security challenges facing the United States. The NSS is closely studied by a few journalists, national security experts, and foreign leaders. Most Americans’ eyes, in contrast, glaze over when they see a story about the NSS. But the NSS provides a great optic for recognizing each administration’s priorities when it comes to addressing threats. Bush listed his. Obama’s differed. But comparing them both to Trump’s is revealing.

There are some stark differences. Bush’s first NSS, released in 2002 in the aftermath of 9/11, focused predominantly on two issues that became the cornerstones of the neoconservative agenda: preventive intervention in terrorist enclaves and global democracy promotion. The “axis of evil” of Iran, Iraq, and North Korea featured prominently. But neither China nor Russia were mentioned as enemies. Bush’s second-term report, in 2006, reiterated those themes with the statement that his administration had two pillars to its strategy: “The first pillar is promoting freedom, justice, and human dignity.” The second entailed “confronting the challenges of our time by leading a growing community of democracies.” Both required military preeminence.

Barack Obama also published two NSS reports—in 2010 and 2015. The 2010 report signaled a clear departure from Bush. It optimistically heralded the influence of globalization—and the subsequent increase in various economic, people, and resource flows—on the lives of Americans. America could and should complement its military power with its economic and diplomatic tools to achieve “national renewal and global leadership.” The report focused on education, science, and technological development. “Simply put, we must see American innovation as a foundation of American power.”

Five years later, in Obama’s second NSS, his administration vastly expanded its lists of core security threats to include elements never discussed before. A participant in that administration confidentially described that NSS to me as a “laundry list” because it included so many elements. Terrorism, homeland security, and opposing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction were highlighted. But health, pandemics, and climate change were mentioned for the first time, as were economic insecurity and the assured access to shared spaces—“cyber, space, air, and oceans—that enable the free flow of people, goods, services, and ideas.” Iran was mentioned—but in terms of its responsibilities, not as a member of the “axis of evil.” Collectively, the key elements of this Obama NSS embraced a human security agenda that surpassed anything American policymakers in the 1990s, or U.N. officials, could have anticipated.

In a summary statement, the report suggested:

When we uphold our values at home, we are better able to promote them in the world. This means safeguarding the civil rights and liberties of our citizens while increasing transparency and accountability. It also means holding ourselves to international norms and standards that we expect other nations to uphold, and admitting when we do not…. For the sake of our security and our leadership in the world, it is essential we hold ourselves to the highest possible standard, even as we do what is necessary to secure our people.

Trump’s NSS

Donald Trump’s first NSS, published at the end of 2017, strikes a markedly different tone from either Bush’s or Obama’s. It is reputedly based on the befuddling notion of “principled realism,” one that relies on overwhelming power and yet “is principled because it is grounded in advancing American principles,” consistent with an “America First” strategy, which is a “positive force that can help set the conditions for peace, prosperity, and the development of successful societies.”

Crafted by H.R. McMaster before his departure as national security advisor, the NSS reiterates several points that candidate Trump emphasized on the campaign trail. The world is a forbidding place full of lurking threats. The country now operates in a world of great power competition with “revisionist” powers—China and Russia—that seek to destroy the international economic and security order created by the United States. In a nod to Bush’s axis of evil, regional dictators (like Iran and North Korea) “spread terror, threaten their neighbors, and pursue weapons of mass destruction.” But there are also new threats that are the product of globalization. The greater flow of people across borders—despite the fact that only 3.3 percent of people in the world are migrants—takes on a frightening dimension because they encourage illegal migration, crime, and jihadi terrorists. Enhanced free trade without fair and reciprocal agreements generates job insecurity at home by encouraging Americans to buy cheap, subsidized foreign goods. It also enhances the prospect of biological, chemical, and nuclear threats because of the illegal smuggling of fissile materials and parts by pariah states and otherwise legitimate corporations, which, knowingly or ignorantly, ship components that can be used to build manufacturing facilities or weapons. The unfettered flow of intellectual property such as encrypted technologies and innovative patents, in exchange for market access to China, weakens the national security base. Technological innovation has generated cyber concerns about control of our critical infrastructure. Transnational criminal organizations tear “apart our communities with drugs and violence.” American energy “dominance” must be prioritized—and, predictably, there is no mention of climate change.

The report is riddled with the kind of contradictions we have come to expect from the Trump administration. It stresses, for example, the importance of international institutions and multilateral alliances, reflecting both McMaster’s and Defense Secretary James Mattis’s beliefs, even as Trump scorns multilateralism and embraces unilateralism—for instance in rejection of the Paris climate agreement and in the movement of the U.S. Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, officially recognizing it as the nation’s capital. The report emphasizes that U.S. strategy should take a whole-of-government approach that includes the use of diplomatic instruments, even as the administration has gutted the State Department and weakened its morale. And in a glaring oversight, it invokes the specter of threats and the benefits of action: “The United States is deploying a layered missile defense system focused on North Korea and Iran to defend our homeland against missile attacks,” without ever discussing the risks associated with such strategies. Assessing costs, benefits, and risks is the hallmark of every variant of realism except, apparently, principled realism.

In key ways, the Trump document resembles elements of an NSS released during the darker days of the Cold War: with states as the dominant focus, geostrategic competition the primary concern, and the regulation or simply elimination of various kinds of flows and the reestablishment of strong borders as essential policy responses. Yet, surprisingly perhaps, even Trump’s NSS includes elements of the human security agenda. The effects of crime, drugs, and health-related issues are all prominently discussed. But the human and national security balance obviously starkly differs between the Trump and Obama versions, as does their appeal to specific constituencies when it comes to who is targeted. Trump’s NSS—with its focus on bravado and aggression directed against America’s geostrategic and economic competitors and migrants and criminals—clearly appeals to his core electoral base.

The next two years

It is easy to dismiss reports such as the NSS in an age when opinion polls suggest that the public has historically low faith in America’s political institutions. But Trump’s NSS has served as a reliable guide to his administration’s policies to date. He has spent his first 18 months in office asserting American unilateralism. The move of the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem mentioned earlier is a major example. But so are the redeployment of the U.S. Navy to the Korean Peninsula and the imposition (and, in some instances, rescinding and then re-imposition) of sanctions against China, Iran, and Russia. He has introduced trade sanctions against America’s closest allies and aborted plans to enter into the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement, attempted to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement in pursuit of narrow American trade interests, and withdrawn the United States from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran—all on the grounds that these agreements contravene American interests. And military deployments to Eastern Europe to buttress forces against Russian aggression have continued unabated despite his insistent complaints about the insufficient contributions of NATO allies as part of America’s new geostrategic rivalry. Nearer to home, Trump has stepped up the deportation of migrants and enhanced border resources to stop the flow of new arrivals. All this is justified in the name of protecting Americans from threats, at home and abroad.

The abiding question is whether Trump can in fact address America’s fears through these combined strategies. The answer is evidently “no” because the security blanket that Americans demand today is just too expansive, and even America lacks the resources to address every threat. Much of what administrations do is political. Trump epitomizes that behavior. He is able to appeal to elements of his electoral base by tapping into the part of the culture that embraces the idea of brazen American muscularity; offers a forthright, defiant attitude; and often champions disruption for its own sake. He may even be able to please his supporters by summarily withdrawing from agreements, such as the Iranian one, that he’s described as dumb deals. And he may be able to do a few things that actually do protect them, as his unrealized promise to address the opioid problem suggests. But ultimately, while he can, for electoral purposes, tap into that part of their angst that sees threats everywhere, Trump is no more able to address the consequence of our underlying pathology—that growing roster of fears and insecurities—than his predecessors were. He has just promised to tackle different ones, using methods that often confound American political conventions: trade tariffs against allies to protect jobs, looser rules of engagement in Afghanistan to protect against the Taliban and ISIS, and harsher detention and deportation measures to protect against “criminals” and bogus asylum-seekers.

The same day that Trump announced American withdrawal from the Iran agreement, the World Health Organization made another announcement that received comparatively little coverage in the United States. Ebola had reappeared in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Last time it appeared, in 2014, Obama provided aid and sent 3,000 American troops to help fight the outbreak to stop its spread. But, despite these measures, 11,300 people died, and it still resulted in a diagnosed case in New York. Unlike Obama, Trump’s immediate response was to rescind a $252 million fund put aside for tackling the virus. He doesn’t consider it enough of a threat to justify any American support, and his base has no interest in, to employ Trump’s reputed description, a “shit-hole” African country. Then, in late May, the U.N. issued a report on extreme poverty. The U.N. Special Rapporteur Philip Alston, commenting on the Trump administration’s policies, said that Americans who already struggle to make a living face “ruination” due to the prospect of losing access to health care. And some, he warned, faced the realistic prospect of “severe deprivation” of food.

The line between human and national security threats has become imperceptible, as this assertive president and his Republican allies further erode America’s domestic safety net and pursue international policies last seen at the height of the Cold War. Now these are threats that should make Americans restless as they contemplate their fears and try to sleep at night.

Simon Reich is a professor in the Division of Global Affairs and Department of Political Science at Rutgers Newark. His new co-authored book (with Peter Dombrowski) is titled, The End of Grand Strategy (Cornell University Press, 2018). Reich is currently a visiting fellow at IRSEM in Paris, supported by the Gerda Henkel Foundation.

0 Comments