Judgment. Responsibility. Guilt. Crimes. Justice.

Throughout The Memory of Justice, Marcel Ophuls’s sprawling 1976 jeremiad on the Nuremberg trials, these are the terms that spring into action in nearly every scene. I have watched this film dozens of times; I have devoted countless hours to taking notes and rewinding key moments and sleeping and dreaming and eating and waking, all while inundated—saturated, really—by my own memories of justice.

My first introduction to Ophuls was in college, via his acclaimed 1969 documentary, The Sorrow and the Pity, a film that had been banned from French television for a dozen years due to its blistering and revelatory portrait of French collaboration and resistance during the Second World War. I had written my undergraduate honors thesis on French Holocaust documentaries, in part focusing on this film, and had even managed to track down the cineaste himself for an informal interview. One blustery night in Paris, the Franco-German-American Ophuls met me at the Café de la Paix (he had faxed me the address, shunning all other forms of communication). I recorded the conversation, fumbling with the microphone, while he smoked and spoke in his raspy, distinctive (but ambiguous) “European” accent, interrupting me now and then, prodding me with what he thought were the “right” questions. In the end, he hated my thesis—absolutely hated it—and to this day I look back at his faxed critiques whenever I feel that I need a reality check.

What I did not know at the time was that The Sorrow and the Pity was far from Ophuls’s most important, most piercing film: that title belongs, rather, to The Memory of Justice. You have probably never heard of this film—I can almost guarantee it—and there’s a reason for that. The two-part, nearly five-hour documentary practically disappeared after its limited release, only to trickle back into consciousness thanks to its 2015 restoration by the Film Foundation. Across its ambitious two parts—“Nuremberg and the Germans” and “Nuremberg and Other Places”—Ophuls draws parallels between the war crimes committed by the Nazis during World War II and those committed by the Americans in Vietnam and by the French during the Algerian War of Independence. In addition to combining extensive archival footage of Nuremberg, the shocking Allied films of the liberation of the camps, cultural life in post-war Berlin, devastation in Vietnam, and so much more, Ophuls also weaves dozens and dozens of interviews with former Nazis, resisters, Nuremberg prosecutors, whistleblowers, artists, and political commentators. The result is not always seamless: the first few minutes alone hit you like a wave. It is as if Ophuls, along with his editor, Inge Behrens, was purposefully attacking you from all sides: drained, stripped of all sense of time or place, unaware of the hours passing by, you are forced to give in and let go, to go back to the scene of the crime.

My connection to this film runs deep. My grandfather, Daniel Ellsberg, appears as one of Ophuls’s key witnesses. In 1971, Ellsberg released the Pentagon Papers to newspapers including The New York Times and The Washington Post. They revealed a top-secret study of the history of the Vietnam War, thereby throwing into question the true nature of American involvement. (He was arrested and faced 115 years in prison, though the charges were dropped due to gross government misconduct.) My own role as spectator or scholar has become undoubtedly complicated.

I have spent literal years working on this film—first as a master’s student, writing a 100-page thesis in French at my Parisian university, and now as a doctoral candidate, punishing myself whenever I allow my attention to drift. I followed the trail of Marcel Ophuls, which led me from my liberal arts college in western Massachusetts to France. I have interviewed Ophuls himself numerous times, as well as Hamilton Fish, the film’s producer (and the editor of The Washington Spectator), and, of most personal importance, my grandfather. I have sought answers to the questions put forth by Ophuls in this, his most obsessive opus: is there such a thing as collective, versus individual, responsibility? Can one be both legally innocent and morally guilty? Does universal justice exist? After three long years of dedication to Ophuls and to his film, I recently decided to quit my Ph.D. program. The questions I am asking myself today are decidedly different: What now? Just what am I to do with The Memory of Justice?

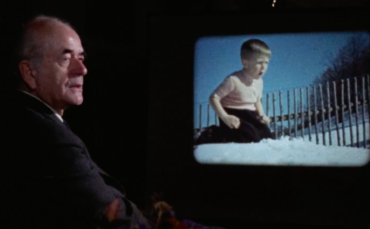

Albert Speer in The Memory of Justice.

The first few minutes of The Memory of Justice resemble an intricate mosaic: interviewees flit by, one after another, their voices carrying over archival footage of the Nuremberg Trials and the Vietnam War. Each testimony serves as a tiny shard, later to be assembled into one expansive piece; during these initial moments, though, it is normal to feel overwhelmed. Much like Claude Lanzmann’s seminal 1985 film, Shoah, The Memory of Justice relies on multilingual testimonies: German, English, and French. Ophuls, the German-Jewish-born son of director Max Ophüls (Marcel forgoes the umlaut), was forced to flee with his family to Paris at the onset of national socialism. After crossing the Pyrenees into Spain, the Ophuls unit settled in Hollywood, where Max continued a successful career. Many of Marcel Ophuls’s films rely on a triad (France, the United States, and Germany) representing both native and adopted lands; this minute focus often comes at the expense of other players but makes the utmost sense. As Ophuls switches dazzlingly from German to English to French with his participants, one can almost sense his own displacement, his own feelings of belonging or betrayal.

This represents just one aspect of the intensely intimate nature of The Memory of Justice; Ophuls himself has stated that he is proudest of this, his most personal work to date. Within 30 minutes of the film’s opening, we cut to a shot of the auteur’s home. The caption reads: “A Birthday Party: The author and his family.” We are introduced to Regine, Ophuls’s German, gentile wife, as well as his three daughters, Catherine, Danielle, and Jeanne.

“What do you think of my making this film?” Marcel asks his wife. She admits that she is none too pleased, that she has been dragging this “skeleton in the closet for all the time of our marriage,” and that she hopes that the family will “get over it.” “Are you thinking of your father?” he continues. Regine hesitates before finally responding, “Well, perhaps . . . he was neither a Nazi nor a Party member, but he was no exception to the other people.” We hear Marcel’s voice, prodding, “Why must people be exceptions?”

The question of “exceptionalism” lies at the heart of The Memory of Justice. Through his careful interviewing of witnesses, such as Nazi Albert Speer or resister and Auschwitz survivor Marie-Claude Vaillant-Couturier, Ophuls examines the motivations for, and the consequences of, collaboration, resistance, and everything in between. After years spent studying this film, I have come to realize that collaboration with oppressive leaders and systems is stunningly normal and far from extraordinary. To be clear, I am not referring to the Eichmanns or Himmlers of this world—those who were astoundingly capable of strategizing and planning the destruction of Europe’s Jews—but those at the bottom of the power structure, those who neither posed questions of those surrounding them nor investigated for more information. These “little guys” (a term thrown around by numerous subjects in the film) are not, as the chief counsel for the prosecution at Nuremberg, Telford Taylor, pronounces, “monsters,” but rather “ordinary people, people like you and me.” If Lanzmann’s Shoah gave voice to the victims of the Holocaust, Ophuls’s The Memory of Justice does what might seem unthinkable: It delves into the psychology of the perpetrators, breaking them down from evil masterminds into small, recognizable men.

At the very end of the film, Marie-Claude Vaillant-Couturier—a member of the French Resistance who was captured and tortured, and who survived lengthy stays at Ravensbrück and Auschwitz—describes the weight of responsibility she experienced at Nuremberg. She says, “I had the feeling that I must speak out, on behalf of all my friends who had died, on behalf of all those who had been exterminated. And that I had to say so, speak out, and not forget anything.” Ophuls cuts to the crisp, black-and-white footage of Vaillant-Couturier leaving the stand, crossing the vast courtroom, passing in front of the accused: “Leaving the stand, I said to myself, ‘This is the minute of my life. I want to see them close, too, the expressions on their faces.’ And I looked at each of their faces in turn. They looked like ordinary people with a normal side to them.” Ophuls freezes this moment, prolonging the confrontation between the resister and those who were responsible.

The constant reminder of the mediocrity and “ordinariness,” the “normal side” of these Nazis, our signifiers of evil, represents one of many radical acts of empathic listening and witnessing by Ophuls. (Without explicitly using the phrase, Ophuls’s film builds on Hannah Arendt’s famous notion of the “banality of evil.”) Sometimes, however, the film can be guilty of queasy identification, as demonstrated by the testimony of Ophuls’s major witness, Albert Speer. Speer, former minister of Armaments and War Production of the Third Reich, as well as Hitler’s chief architect, stands as one of the film’s—one of history’s—most guiling, charming, and ambiguous criminals. We are first introduced to Speer in the snow outside his house, where he admits to having given hundreds of interviews since his release from Spandau Prison, the site of his incarceration for two decades. He reiterates what he proclaimed at Nuremberg: “The trial is necessary. Even authoritarian regimes involve collective responsibility.” Later, we find ourselves in a dark living room, where Ophuls and Speer watch the former Nazi’s home movies. The scene creates a bizarre, forced intimacy with the war criminal; you find yourself nodding, appraising Speer’s charm . . . and then you start to kick yourself.

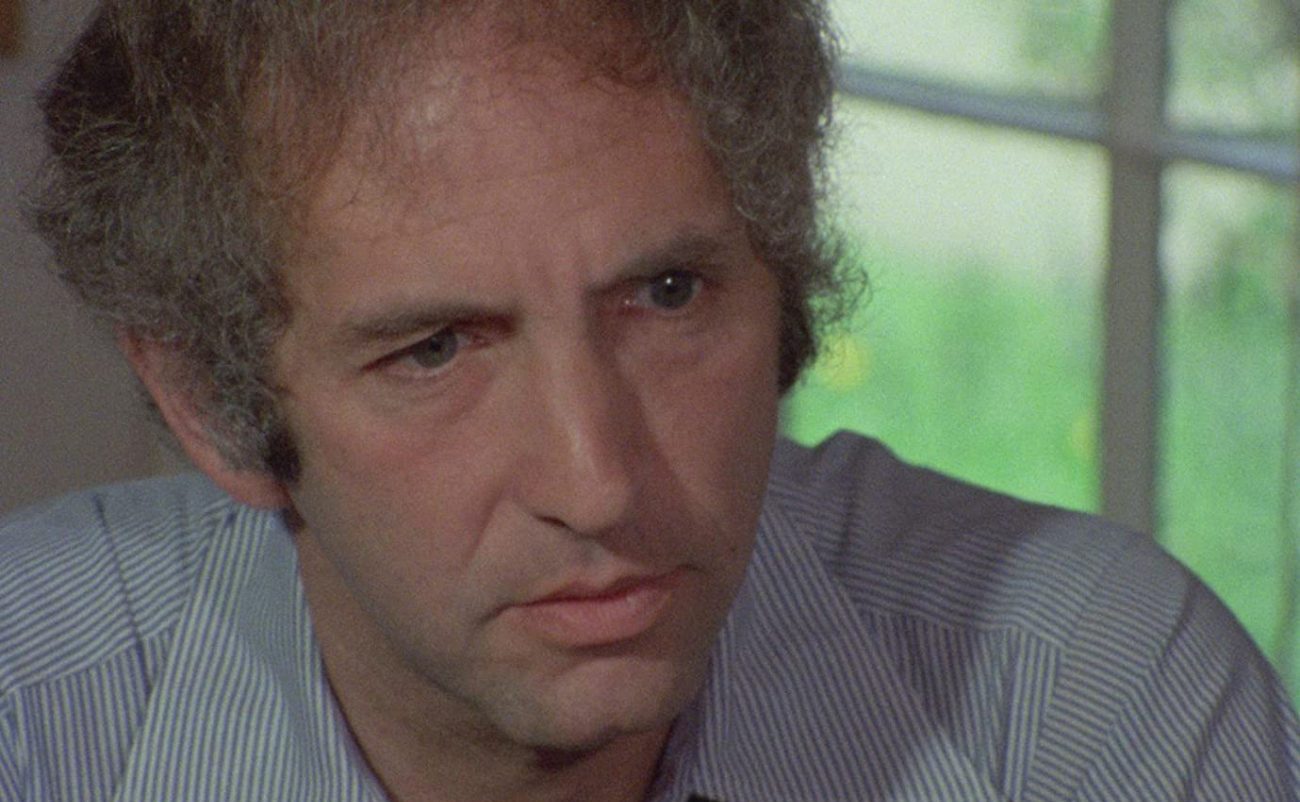

This brings me to December 2017, when I visited my grandfather, Dan Ellsberg, in order to interview him about his role in the film. Oddly, he admitted that he had never seen the whole, five-hour documentary and remembered very little of the film shoot, except for his purported clash with Ophuls. I was not surprised to learn that the two intellectuals—stubborn and often haughty—butted heads, even as they spoke of the other with grudging respect.

After fumbling with Dan’s Fire TV, we finally got the film to start. Dan set himself up with a yellow legal pad and proceeded to do what he does best: observe and take notes. In the beginning, he seemed to nod enthusiastically whenever Telford Taylor spoke, but the mood changed dramatically when Albert Speer appeared. When Speer described his fellow accused as narrow-minded—“often decent people . . . [who] refused to take responsibility in a broader sense. . . . They feel only responsible for the activities that have been delegated to them personally”—Dan physically inched forward in his rocking chair, poised to say something in front of the TV. Later, he was mesmerized, murmuring “Yes, that’s it, yes,” as Speer continued: “I wouldn’t attempt to deny that I’ve often acted in an opportunistic way, but no more really than everyone does in daily life, or in business when dealing with his boss. But I do believe that you can almost unconsciously get so absorbed in a job that all the protective barriers set up for you by the warnings of friends and relatives crumble and disappear. And you become, as they say, blinded by ambition.” Dan was entranced, attempting to communicate, somehow, with this dead Nazi—and, perhaps, attempting to communicate something scary from deep within himself: “Speer sounds to me like me. . . . I can’t help but identify with him.”

My grandfather acknowledged that Speer was “higher up” than he ever had been. But after working for the State and Defense Departments, and later as an analyst at the Rand Corporation, the notion of compartmentalization—of shunning or evading “guilty knowledge,” as he himself put it—continues to haunt him. “When I see Speer,” said Dan, “I’m looking at a man who has ‘awakened,’ in effect. And maybe he awakened in order to save his life—that’s possible. . . . I don’t know what Speer’s motivations are, but I’m listening to a man who is seeing pretty clearly what he was part of . . . so I identify with him in that respect.” Dan explained to me that he wishes he had leaked the Pentagon Papers far earlier, which could have perhaps spared thousands of lives, as well as his trove of documents that revealed the catastrophic nuclear war program the United States was spearheading, which threatened the lives of millions more.

It is difficult for me to convey the emotional whiplash I felt while watching my young grandfather in his blue, collared shirt during his 1974 interview with Ophuls and then to hear that, to this day, he carries around an immense weight of guilt, a feeling of responsibility. Have I too inherited this responsibility? His deep identification with Speer, as it turns out, had started even before the making of this film, when he wrote a chapter in his book Papers on the War called “The Responsibility of Officials in a Criminal War,” based in part on a lecture he had given in Boston in the spring of 1971. My grandfather had started to read parts of Speer’s 1969 memoir, Inside the Third Reich, aloud to his audience, believing at first that he was “detached.” But then, thinking of Robert McNamara or McGeorge Bundy, “I heard my own voice growing low and halting. I told my hearers, ‘I am finding this difficult to read.’ After a moment, I went on, but I brought the talk to an end. I knew that it was myself who was the listener, my eyes, my voice responding to these indictments. I was there, too, however minor and ‘innocuous’ my role.” My grandfather damningly concluded: “‘My moral failure,’ Speer says, ‘is not a matter of this item and that; it resides in my active association with the whole course of events.’ That accusation—and the more specific one of willful, irresponsible ignorance and neglect of human consequences—are truths that I must live with. As should any American official known to me who has been associated with Vietnam.”

When I wrote my master’s thesis on this film, I sent the finished product to Marcel Ophuls. Remembering his earlier reaction to my undergraduate thesis, I waited for his response in fear, clenching my fists preemptively. He finally did respond by fax, opening his message with one word: “FABULOUS!” I had finally done it—I had satisfied Ophuls. He then addressed my grandfather, writing, “Dear Daniel, Albert Speer was a charming man, a great liar, and a dangerous criminal. The only thing you have in common with him is charm. So I really think you should stop identifying with him or have a guilty conscience, or we’ll send you back to that psychiatrist who was burglarized by Nixon and his gang. Very sincerely yours, Marcel.”

Dan never did read my master’s thesis: to be fair, it was in French, so I cannot entirely blame him. But there is a part of me—a large part, if I am honest—that is still trying to get through to my grandfather. I wish I could ease his pain, his deep, wrenching guilt, to reassure him that I have taken some of his burden and tell him that he had acted—that he was no Speer—and that he had made me proud long before I was born. I could still tell him these things.

As for today, the film’s “lessons” about collaboration and moral compromise are as relevant now as they were in 1976. Evil does not always come swathed in swastikas; reprehensible acts are not committed solely by Nazis or the bloodthirsty. The reality is far more troubling: shunning knowledge, evading the weight of responsibility and guilt, covering for the “boss” or those in positions of power, are ways that ordinary people negotiate with moral corruption every day. We can see the wide web of complicity that entangles Cabinet officials who pledge fealty to Trump at all costs; the contractors who build ICE detention centers; the police unions that turn a blind eye to racist abuse and, all the way down, the rest of us who watch on TV and change the channel. Anyone—not just bureaucrats but normal citizens—can engage in willful ignorance; we each have to ask ourselves the question of where we draw the line in a society marked by systemic racism and rampant inequality.

I do not know what will come next, but for now, I am preparing to let go of Marcel and The Memory of Justice, all while holding on to that promised vision of a just world.

Catherine Ellsberg is a writer and teacher based in Paris. This piece was originally published online at Bright Wall/Dark Room.

0 Comments