The scarcely 22,000 voters of Ohio’s Ottawa County, nestled on the south shore of Lake Erie, have picked the winning presidential candidate for more than half a century, rarely straying more than a few points off dead center.

The county’s largely working-class voters twice favored George W. Bush by between two and four points and opted for Barack Obama back to back with similar margins. Then, three years ago, they voted for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton by 20 points, more than double the eight-point advantage the president claimed statewide.

Now, with an otherwise steady economy threatened by trade war, national politics defined by scandal and mudslinging, and news cycles devoted to invective rather than information, the county’s folk are again taking stock. Trump still has plenty of fans in this summer resort town, but others who once backed him say they are shopping for a better deal.

“I liked what he said to begin with, about getting things back to the way they used to be,” offers Tina Petersen, 71, a retired nurse who’s spent her life in Port Clinton, the county seat. “But it didn’t happen. He is an idiot. He opens his mouth before his brain is in gear.

“I don’t know who I’d support,” she says of the Democratic field. “I am listening.”

Long a swing state, Ohio in recent years has turned near solidly red, with Republicans controlling the legislature, the governor’s mansion, every senior state office, one of two senate seats, and three-quarters of the 16 seats in the state’s congressional delegation.

While most of the state’s large urban centers remain solidly Democratic—and some suburban voters are evidently shifting left—Republicans have solidified their hold on rural and small-town voters.

“It’s hard to remember a time when Ohio wasn’t considered a toss-up,” the Cook Political Report notes. “Today, it’s hard to see how a Democrat wins here.”

Local Republican operatives say that Trump supporters’ widespread embarrassment about his tweets or personal behavior is overcome by their approval of his handling of the economy, his appointment of two conservatives to the Supreme Court and scores of other federal judgeships, his trade fights, and his immigration crackdown along the border with Mexico.

“I wish he would filter his thoughts a bit. But Trump will win again because he’s trying to do everything that he said he would do,” says Tim Clemons, 67, a Vietnam veteran who’s retired from the Merchant Marine.

“You vote for who you think can change things,” says Clemons, who voted for Obama twice before jumping to Trump. “I think we need a little rebellion.”

Democratic politicians concede that Trump’s outsize victory here in 2016 makes Ohio his to lose next year. But they, and some political analysts, argue that longtime party supporters and independents turned off by Clinton—they either voted for Trump, someone else, or no one at all—will see next year’s vote differently and vote accordingly.

“A lot of people came to the [2016] election thinking there has to be a change. Donald Trump [now] is in a very similar situation,” says Herb Asher, emeritus professor of political science at Ohio State University. “Some of those behavior patterns that attracted people to him are not so attractive anymore. . . . They’re waiting to see what the Democrats offer.”

Though few would bet an election on opinion surveys this early on, a Quinnipiac University poll in July gave Joe Biden an eight-point lead over Trump, with Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders polling even with him.

Another poll in early October, this one by Emerson University, gave both Biden and Sanders a six-point lead in a matchup. Warren and others also polled within the margin of error.

The Emerson poll showed Biden with 29 percent support for the primary, within the margin of error of Sanders’s 27 percent but leaving Warren eight points behind. The remaining Democratic contenders all polled in the single digits. Clinton beat Sanders in the state’s 2016 primary 56 to 43 percent.

Warren in recent weeks has overtaken Biden in other polls, both nationally and in the early contest states of Iowa and New Hampshire.

The Democratic primary here, as elsewhere, will be a battle between moderate and more progressive platforms and candidates. But Asher and operatives from both political parties say the party’s best chance in Ohio—and likely the Midwest—will be to offer a moderate message rather than a sharp swing leftward.

Crediting Trump’s ability to connect with his working-class base, some argue that how the Democratic agenda is delivered will matter more than the policies it actually promises.

“If I trust you, I vote for you,” says Fred Strahorn, 54, a Dayton politician who has represented a largely African-American district in the Ohio legislature for nearly 20 years, serving the last four as leader of the body’s Democratic caucus. “This isn’t rocket science.”

“We always put the facts in front of the relationship,” he says of Democratic candidates. “Most people vote on the relationship.

“Don’t assume you know what they want,” Strahorn counsels, especially of white working-class voters. “If you disrespect them, you do it at your peril.”

Static growth of Ohio’s population, now about 11.7 million, has brought waning influence in the electoral college. The state’s current 18 electoral votes are eight fewer than a half-century ago. Another vote is expected to be lost following next year’s census.

Still, the state’s mix of Democratic-leaning industrial cities, prosperous and politically shifting suburbs and reliably conservative rural counties makes it a good reflection of the overall Midwest vote that could well decide the presidency next year. The Ohio electorate’s largely middle-ground mentality continues to make it the best measure of the crucial region’s political pulse.

ALWAYS REMEMBER YOU ARE UNIQUE, winks a bumper sticker pasted to the back-bar mirror in a gritty downtown Youngstown tavern. JUST LIKE EVERYONE ELSE.

Though moderation usually wins the day in politics here, Ohioans can have a contrarian—some would say ornery—streak when it comes to candidates.

Texas billionaire Ross Perot, who based much of his 1992 presidential campaign on opposition to the North American Free Trade Agreement, took 21 percent of the Ohio vote, two points higher than his national share. Alabama segregationist George Wallace won nearly 12 percent of the Ohio vote in his 1968 White House bid, his best showing in any of the Midwestern states.

Ohio produced many of the Union’s best generals and too many of its casualties in the Civil War. But huge numbers of Ohioans sympathized with the Southern cause, especially those in the southern and eastern stretches of the state. Some rural homes this fall are flying either the Confederate battle flag or banners that juxtapose the Stars and Bars—a symbol of enduring racism to African-Americans and many others—with the Stars and Stripes.

While Democrats can take the White House without winning Ohio, victory here is essential for Republicans, says Kyle Kondik, a noted expert on Ohio’s predictive track record on national elections and managing editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball, the newsletter of the University of Virginia’s nonpartisan and authoritative Center for Politics.

“If Trump is underperforming his 2016 margin in Ohio significantly,” Kondik says, “it probably means that he will have a hard time winning similar states that are more Democratic than Ohio, namely Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.” The long-term trend in Ohio toward Republicans “seems real,” Kondik says, echoing other analysts.

But Democratic operatives insist they can win with a surge of their urban core of minority and young voters, by regaining at least some working-class white voters and by attracting more of the educated suburbanites who have been shifting their way. To do that, they’ll have to maintain a tight discipline among squabbling tribes of moderates and progressives, keeping everyone inside a large and raucous tent.

“The Democratic Party has to step up and manage its brand,” says Strahorn, the longtime state lawmaker. “This will be a dog fight.”

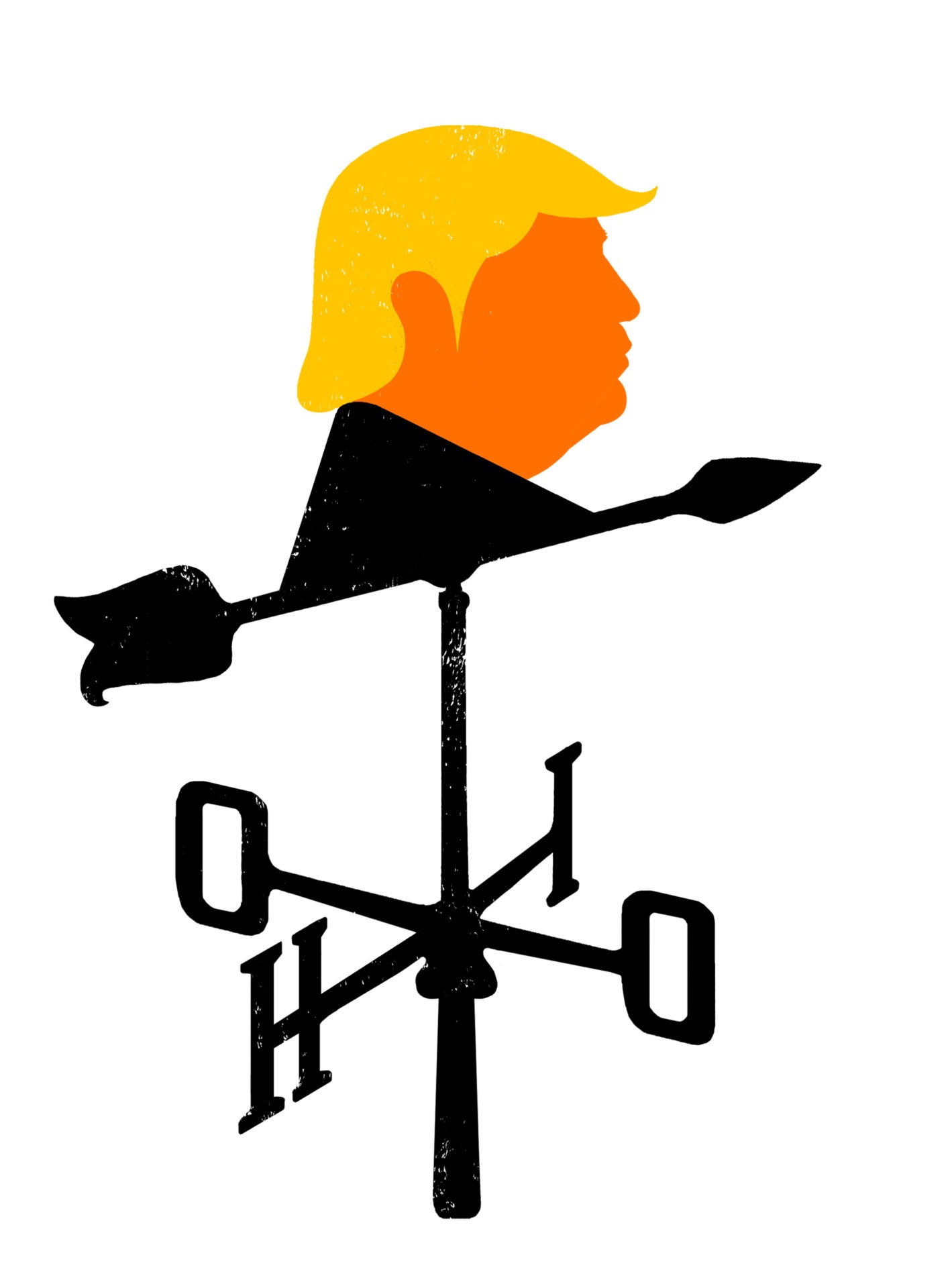

Illustration by Edel Rodriguez

Jobs and white working-class voters

Democrats seem likely to hold onto their advantage in the big urban centers of Columbus, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Toledo, and Akron, where urban liberals and African-American voters gave Clinton wins by solid margins.

The party’s standing with white working-class voters will be tested. Globalization battered industrial communities like Montgomery County, anchored by Dayton in the southwest corner of the state and Youngstown’s Mahoning Valley in the northeast, near the border with Pennsylvania.

Youngstown rose to prosperity a century ago manufacturing steel. Dayton and surrounding communities became industrial engineering and factory centers, largely feeding the automotive and appliance industries.

Youngstown’s steel industry collapsed through the 1980s. Much of Dayton’s manufacturing was lost to Mexico, under 1994’s North American Free Trade Agreement, and then to China following that country’s entry into the World Trade Organization at the beginning of the 2000s.

Each city’s region lost as many as 50,000 manufacturing jobs in the ensuing decline. And in each place, thousands of factory floor jobs that paid $30 an hour were lost, replaced by others paying half as much, at best.

“Our jobs went to Mexico. Trump came in and said ‘I’m going to change NAFTA.’ That hit home,” says Tony P. Hall, who as Montgomery County’s Democratic U.S. congressman for 24 years, until 2003, served through much of the decline. “If you’re running for office in Ohio, you must talk about jobs,” Hall says. “Hillary didn’t.”

The General Motors plant that produced SUVs in a Dayton suburb was closed in 2008. A Chinese supplier to GM of automotive windows has replaced it, paying as little as half as much as GM did. An effort by the Union of Auto Workers to unionize the plant later failed.

Citing plummeting demand for the compact car produced there, GM shuttered its sprawling plant near Youngstown last summer. The company spurned demands by the UAW, which launched a strike in September, to reopen it by shifting production of SUVs or trucks from Mexico.

Though many factors added to manufacturing’s travails throughout the Midwest, for Ohioans NAFTA remains the symbol of the collapse. The president touts a replacement treaty negotiated by his trade representatives as a great improvement. Known as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, the proposed treaty is widely criticized by Democrats as little more than a warmed-over NAFTA, and not labor-friendly enough. The bill now languishes in the House of Representatives (see “Proposed USMCA is Just Trumped-Up Version of Old NAFTA Treaty,” The Washington Spectator, December 2018).

Though negotiated by the first Bush administration, NAFTA—which dropped trade barriers between the United States, Mexico, and Canada—was signed and promoted by Bill Clinton. That, for better or worse, has linked NAFTA and globalization in general with his family’s political brand.

“Democrats changed union members’ political bent because they were weren’t offering what we needed,” says John Hayes, who heads the Construction and Building Trades Council in Dayton. “The union movement just didn’t want Hillary.”

But Hayes says that while many union members back Trump’s immigration crackdown, they are less enthusiastic about his administration’s overall policies toward organized labor, throwing its support for him into question. “He’s going to have to fight a little harder for it this time,” Hayes said.

People in both Dayton and Youngstown still repeat, unprompted, Hillary Clinton’s comments during the 2016 race about “putting a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of business” and branding half of Trump’s supporters as “racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamophobic” people who constitute a “basket of deplorables.”

Although they were taken somewhat out of context, both comments were effectively used by the Trump campaign to paint Clinton as hostile to working-class concerns.

“What she conveyed to people who work with their hands was, you’re not valuable,” says lawyer Dave Betras, who recently resigned as head of the Mahoning County Democratic Party in Youngstown after a 10-year stint. “If you insult people, you are not going to get them to vote for you.”

Both Dayton and Youngstown have been undergoing something of a resurgence, with new industries coming in and once boarded-up downtowns being spruced up.

Youngstown’s reset is anchored by an upscale hotel and restaurant in a historic building; Dayton’s with gastropubs, an art scene and condominiums designed for middle-class families and retirees. But still houses stand abandoned and derelict just outside the city centers, and police stations post updated tallies of opioid overdoses on street-front notice boards.

And each town has been slammed with fresh trouble. A mass shooting that killed nine and wounded several dozen in downtown Dayton’s premier nightlife area followed Memorial Day tornadoes that cut a path of destruction through close-in neighborhoods, many of them impoverished.

This year’s shuttering of the GM plant in Lordstown, just outside Youngstown, was followed by the closing of The Vindicator, the city’s daily newspaper. Signs in front of area churches urge people to “not give up” and remind them that a positive attitude brings its own reward.

“People here are $400 or $500 away from economic catastrophe,” Betras says of Youngstown. “Until candidates talk about paychecks, pensions, and health care, everything else is a side dish.”

Idled workers now picketing at the closed gates of the Lordstown plant—part of the nationwide strike against GM—smirk when they repeat Trump’s 2017 vow to bring the jobs back, and his urging them to not sell their houses or give up hope.

“If I was inside that place, working, and you came to talk to me, I’d talk Trump up,” says Edward Bak, at 42 a third-generation employee at the Lordstown plant, who is manning a strike picket line at the entrance. “But I’m outside the gate, and I don’t have a good thing to say about the man.”

After losing his $20-an-hour job inside the plant, Bak has been making do with odd jobs in the Youngstown area, reluctant to uproot his family for jobs GM is offering elsewhere.

“I don’t know if I thought everything was going to change the moment he got in,” Bak said of Trump, “but I thought we’d be doing better than this. Everything is shutting down.”

But Dayton-area Republicans insist the improving economy remains Trump’s best asset for winning there again, which they agree is essential for him if he is to win Ohio overall.

The area’s voters “can hold improvement in their hand, can feel it and touch it, and they fear it being taken away,” says Tom Young, 55, a financial adviser who sits on the Montgomery County Republican Party’s central committee. “If things change, do I lose my job, will my 401(k) go down, will my wages go down? Will we go back to where we’ve been for 30 years?”

As across much of Ohio, the local Republican Party in the Dayton area is “extremely conservative,” Young says. “We have thousands of foot soldiers. Our ground game is strong.”

“They cringe at some of the things that are said,” Young says of Trump’s personal style. “But it will come down to a choice, and they don’t see another choice.”

Indeed, HELP WANTED signs are common across the state and particularly in the Columbus suburbs. But the jobs advertised by employment agencies offer wages “as high as $14 per hour.”

A study using census data by Policy Matters Ohio, a left-leaning research center based in Columbus, found 2018 median wages in the state were about $18.50 an hour. That’s 50 cents an hour below the national median last year and slightly below Ohio’s median hourly earnings in 1979, adjusted to 2018 dollars. The fastest-growing profession in the state is home health care, which pays an average of $10.50 an hour.

Unemployment stands at 4 percent, statewide, slightly higher than the national average, but job growth is slowing almost to a halt, says Hannah Halbert, project director at Policy Matters. While a national debate continues as to when the next recession will strike, some economists warn that manufacturing is already in negative growth.

“Depending on your zip code, you could have a really different experience,” Halbert says. “If people are voting according to their economic interests, the data suggest they should not be happy with how they are doing.”

Democratic optimists and nonpartisan analysts point to last November’s reelection of Senator Sherrod Brown, a liberal pro-union critic of free trade, who easily won many of the blue-collar corners of the state where Trump had run strongly.

Undoubtedly aided by his incumbent status, Brown won Montgomery County by five points, even as voters elected Republican Governor Mike DeWine by the same one-point margin by which Trump prevailed there.

Brown bested Hillary Clinton’s tally in Mahoning County by 11 percentage points. He matched Trump’s 56 percent win in Ottawa County.

“Some of those who abandoned the party in 2016 are still loving Sherrod Brown,” says David Cohen, a political scientist at the Bliss Institute, a nonpartisan think tank at the University of Akron. “The notion that Ohio is not a swing state anymore is way overblown.”

While the state and the country become increasingly polarized, local politicians stress that the party’s candidates and message—as well as the particular moment in which they hit the scene—still matter.

Some point to George H.W. Bush’s 1988 win over George Dukakis by 11 points in Ohio—three points more than Trump’s smackdown of Clinton here—as proof of that. Hardly anyone would equate the elder Bush’s style with that of Trump.

Bill Clinton defeated Bush by two points in 1992’s three-way race with Perot. He bested Bob Dole by six points four years later, amid his own impeachment turmoil.

“People would like Trump more if he would just keep the hell off of Twitter,” says Gabriel Williams, 54, an unemployed technology worker in Dayton who blames visa-holding Asian immigrants for pushing him out of the local labor market. Immigration, by both undocumented Central Americans across the southwest border and those coming legally from elsewhere, ranks among his major concerns, Williams says.

“The biggest reason Trump is important is he recognizes the change that is taking place,” Williams says. “Trump hasn’t done anything for me personally. But he’s doing what we elected him to do. He’s the right guy in the right job.”

The farm economy is on a downward spiral

Trump won Ohio’s rural counties with 70 percent or more of the vote three years ago. Though few expect that support to wane much, small and perhaps significant cracks have appeared. This has been an anxious year for farmers and the market towns that depend upon them. Black-lettered signs adorn the yards of more than a few farmhouses, counseling DONT GIVE UP.

A wet spring and summer delayed and curtailed planting. Grain prices have been held hostage to both herky-jerky trade negotiations with China and policy shifts on federal backing for ethanol production, which consumes 40 percent of the corn crop.

With only a few fields harvested by early fall, fields of drying corn stalks stood tightly packed across the state. Yellowing soy plants seemed to stretch by the thousands of acres in every direction, engulfing the patches of remaining woodland like a rising tide.

A partial deal announced on Oct. 11 held the promise of China buying some $50 billion in grain and other farm products. And the administration signaled another reversal of ethanol policy that would renew that market.

In announcing the trade deal, Trump urged farmers to buy more land and bigger tractors to bolster grain supply. But there have been too many head fakes already for many farmers to take him up on the suggestion.

An employee of a grain elevator in the corn- and soybean-producing country of central Ohio says most farmers she deals with will “probably vote for him again, because they won’t vote for a Democrat.

“But a lot of them are frustrated with things,” she says, asking that her name not be used, for fear of angering clients. “There are some who come in here and curse him. If there were another acceptable candidate, he probably wouldn’t win.”

Roy Miller, 78, retired from growing alfalfa on 1,400 acres outside Canton in northeast Ohio, says Trump definitely won’t get his vote next year.

“We have a buffoon in office who is killing the farmers. He keeps saying a big deal is coming, but we sure haven’t seen it,” Miller says as he unloads a wagon full of corn, produced on the 100 acres he still farms, at a grain elevator. “If we go through another season like this one, I can see a lot of farmers going out of business.”

On the first Sunday of autumn, Trump flew into the small city of Wapakoneta, the birthplace of Neil Armstrong, 60 miles north of Dayton, to inaugurate an Australian-owned paper recycling plant. It was Trump’s fifth visit to Ohio so far this year. He came to tout the economy.

“This great state of Ohio is open for business,” Trump told a cheering crowd inside the plant, according to journalists present. “Everybody’s looking, and they’re all paying well.”

Only about 500 fans were allowed into the event. Some 1,000 others who had been invited and bused in were turned away. Fewer than 100 other people waited in the grass outside the plant, cheering softly and clapping as Trump’s black SUV passed, escorted by state police. A white-shirted arm waved briefly from the right rear seat.

A mile away, near the main street of Wapakoneta’s charming downtown, Tyler Spearhart, 32, stands in the small yard of the two-story brick home he shares with his husband, flashing a hand-written placard urging trump go home to the busloads of people coming and going from the factory rally.

FASCISTS BUILD WALLS. NEIGHBORS OPEN DOORS, proclaims the t-shirt Spearhart is wearing.

After the last bus passes, Spearhart chats on his porch with Kay McDaniel, 54—a close friend and co-worker at a small home health care agency—and her husband, Bruce, 62, a retired Methodist minister who works as a chaplain in a local nursing home.

The conversation quickly shifts to their fragile economic situations—both McDaniel and Spearhart say they earn less than $11 an hour and can’t afford medical insurance for themselves. They also touch on the loneliness of being politically out of step in rural Ohio.

Spearhart, 32, says he can’t tolerate the hatred that he believes Trump nourishes in the community. He chuckles, recounting how an older neighbor tongue-lashed him for flying an equality banner—the one with a yellow equal sign on a deep blue field. The man mistook the flag as declaring support for the University of Michigan, the traditional rival of Ohio State University’s sports teams.

“It’s just everywhere,” Spearhart says. “But it’s the Republicans who have most of the anger.”

McDaniel says her disgust with Trump ended a lifetime of voting Republican.

“It’s just the way he behaves,” McDaniel says. “I would not have him at my dinner table with my children and my grandchildren. It’s a respect thing at this point. He just is not good for our country.”

Trump not winning style points in the Republican suburbs

Disaffected women voters like McDaniel may prove key to Democrats’ efforts to expand their reach in the once-solid Republican suburbs that may decide next year’s vote, officials in both parties say.

Though Trump easily won most suburban counties—some with two-thirds of the vote or more—taking back at least a share of those voters might not prove as difficult as it seems.

“There is less support for Trump than it might appear,” says Peggy Lehner, 69, a longtime Republican state senator from Kettering, a middle-class suburb of Dayton, who is term-limited from running again. “I don’t know anyone who really likes him. And I am talking about Republicans,” Lehner says. “The unwillingness of the party to go after him when he tweets things that are outrageous just stuns me.”

Lehner originally became involved in politics through her opposition to abortion and, since the early-August massacre in Dayton, has become a leading Republican voice for gun control legislation. She believes gun control is an issue that can find favor among Republicans, especially women.

Still, she says, “Republicans will stay Republicans unless the Democrats give them a good reason to switch. . . . If Democrats go with someone leaning too far to the left, they will fail.”

Democrats are putting a lot of focus on the northern suburbs of Columbus, among the fastest-growing and more prosperous communities in the state. This is John Kasich country. While the former Republican congressman and governor has become persona non grata for many in the state Republican Party, his anti-Trump brand of conservatism still resonates among others here.

Columbus lawyer Charles “Rocky” Saxbe, 73, counts himself among longtime Republicans who have at least temporarily abandoned the party because of Trump. His father, William Saxbe, was a onetime Republican senator from Ohio who, as U.S. attorney general, presided over the final days of the Watergate saga and Richard Nixon’s resignation.

“My dad would be aghast at what’s happening in the White House and what’s happening in the party,” says Saxbe, who is hosting a fund-raiser for Biden next month. “It’s difficult to have a political conversation with folks who still find Donald Trump acceptable.

“They don’t like Trump, but they don’t want to speak out against him,” Saxbe said. “You’re still going to have a close election here. But I am optimistic that people will finally get totally disgusted with him, and Ohio will come back around.”

Many Republican women voters in the Columbus area declined to support Trump three years ago, and still more have abandoned any support for him now, says Barb Lewis, 72, the Republican president of the Delaware County Commission, which includes many of those suburbs.

“It’s a challenge for the president,” says Lewis, who taught campaigns and other political science courses at Ohio State University. “His base is only a third. For him to win, he needs to do better. He still needs to work harder.”

Among the largest and more politically evolving suburbs is Westerville, a formerly sleepy town that has become a sprawling community of 40,000 northeast of Columbus. The Democrats held their October primary debate here, as a nod to the area’s leftward shift.

Anchored by Otterbein University, a private liberal arts institution with 3,000 students, Westerville’s core boasts a shopping district of red brick buildings, with white clapboard houses that line the leafy residential side streets. American flags fly from many buildings and houses. Flowers accent the sidewalks.

Otterbein accepted African-American students and women before the Civil War and served as a way station on the Underground Railroad. A century ago, Westerville also was headquarters of the Anti-Saloon League, whose decades-long efforts culminated in the 1920 adoption of Prohibition.

The town’s competing ideological strains can be seen today in the small museum dedicated to the League in the public library downtown.

“It’s good to limit certain freedoms,” reads one visitor’s comment on a museum bulletin board. “Americans don’t understand and don’t appreciate their freedoms.”

Another visitor demands that “we must legalize marijuana and retroactively forgive drug sentences.” “Freedom for all,” still another declares.

Westerville residents Shannan and Michael Fleet challenge the image of buttoned-down suburbanites. Michael grew up in an evangelical home in Westerville but played professionally for a decade in a rock band touring across the United States before settling into a career as a software engineer. Shannan is an artist who homeschools their four children.

In an amiable Ohio manner, the Fleets describe themselves as pro-life adherents to the “secular homeschool” movement and define themselves as members of a “Christian left” whose interests have been poorly served by Democrats.

Counting progressives and anarchists among their circle of suburban friends, the Fleets enthusiastically voted for Sanders in the 2016 primary while living in northern California’s wine country. The Fleets now think a more moderate Democrat voice holds the best hope for winning Ohio. But they say they’ll vote for whoever is the party’s nominee.

“People are just waiting for it to shake out, and they will support the Democrat no matter what,” Shannan Fleet says. Michael Fleet adds that “Biden and Bernie can win minds. They can’t win hearts. . . . Perhaps Elizabeth Warren is the least annoying.”

Yet progressives in inner-city Columbus argue that the efforts of Democrats to please suburban moderates risk losing at least some of the young progressives, African-Americans and poor inner-city voters.

“The people who volunteer with us are going to vote for anybody who is not Trump,” says Adam Parsons, a leader of Yes We Can Columbus, a grassroots group working on community issues in the center city neighborhoods of the capital. “The people who we are talking to? Maybe not so much.”

“Democrats don’t have a pessimism problem as much as a voter motivation problem,” Parsons says. “There are suburban districts where it makes sense to run a moderate. Statewide, it would be better to run a populist. I don’t see much hope for a party of well-off folks who want to do things for poor people.”

Regardless, Tiffany White, an African-American candidate for this month’s Columbus city council elections, believes Trump’s victory taught her community an important lesson.

“People are tired of the Democrats because they are not doing anything for us,” says White, a single mother who is now raising her addict daughter’s young children. “Columbus had a lot of Bernie supporters, and a lot of those people stayed home last time.”

Now people in her community “know they have to vote or there will be four more years of this,” White says. “It’s important that we get back to democracy.”

Opinions, like football, ebb and flow at the VFW post

Country music twangs softly over the speakers on a Saturday afternoon, as Tina Petersen and a half-dozen friends take a break from watching Ohio State football to talk politics on a patio behind Port Clinton’s Veterans of Foreign Wars post.

The conversation is gentle, a contrast to the strident viciousness on social media and cable news that everyone in the gathering says they abhor.

Most voted for Trump, they say—some in hopes that he’d shake up Washington, others because they couldn’t bring themselves to vote for Clinton. Now a few, like Petersen, say Trump has been a disaster. Others are holding firm.

Bert Fall, 70, says he has almost always voted for Democrats, through four decades as a unionized meat cutter at a grocery chain, but “they didn’t give us nothing.” Trump is a better fit for a working man, he says.

“I’m a Trump person, I can’t help it,” Fall says. “I really think he’s trying to make America great again. I really do.”

Peggy Haer, 57, a cousin of Petersen’s who tends bar in town, says she’s interested in hearing from younger Democratic candidates offering fresh ideas. But “unless he screws up,” she’ll be voting for Trump next year.

Randy Ryster, a 65-year-old retired machinist, says “he’d vote for anybody else” instead of Trump. He adds that he’d like to see “the guy from Indiana, the gay guy” get the nomination.

Having grown up together in town, these friends raised their own families through decades of decline that saw once plentiful jobs disappear as local factories shuttered.

Now tourism, which brings thousands of fishermen and beachgoers to Port Clinton every summer, remains among the region’s only steady source of jobs.

The friends fret that young people have too few chances for good jobs, too little interest in taking the ones still available. Several complain that too much emphasis has been put on a university education, when the country needs more skilled labor.

They agree that health care is a major worry. But many consider the Democratic candidates’ ambitious proposals for universal health care provided by the government as both unworkable and prohibitively expensive.

Though many favor Trump’s crackdown on the Mexican border, several are quick to add that they have nothing against the migrants themselves. Dairy and tomato farms in the area have employed Mexican workers for years and would find it difficult to operate without them.

“We all have Mexican friends,” Fall says. “You need the migrants here.”

After 30 minutes of ricocheting opinions, Petersen shrugs when asked if Ottawa County will continue its near-stellar record on choosing the president. “We’re all working people,” she says. Petersen voted for Clinton but supported Trump in his early days in office. “There isn’t one of us who comes from money,” she says. “But people in Ohio care a lot about what’s going on in the whole country. . . . I think we just go for who we think can offer us the most.

“People here make up their own minds,” she says.

As a staff correspondent for the Houston Chronicle, The Wall Street Journal, and other newspapers, Dudley Althaus has spent his career reporting on politics and other issues in Texas, the U.S.-Mexico border, and across Latin America.

This article is the first in a series of reports from battleground states underwritten by the Bellwether Project, a joint undertaking of The Washington Spectator and the Public Concern Foundation that seeks to broaden the public conversation around social and political issues.

Anybody but Trump. He is a liar, a crook, a traitor and has destroyed or allies, our Park lands, reduced limits on air and water safety. He is trying to gut Social Security benefits that we have paid for and earned, is destroying health insurance and increasing medical and drug costs. We need a candidate that can balance between all parties to do what is best for all people. I don’t see anyone in the Republican fold who can do this.

I did a geographic a long long time ago from OH. Americans (Ohio included) have no idea what suffering is. You can tell this by our country’s collective participation in our “Democracy”

Anyone but Trump but America deserves Trump because America is “on the phone” waiting for the next big distraction, complaining about the other side like we weren’t all complicity polluting the planet to the event horizon while the robber barons steer the collective boat into oblivion.

Have a nice day Ohio!