In 1969, a young Vietnam veteran named Ron Ridenhour wrote a letter to Congress and the Pentagon describing the horrific events at My Lai. The first to bring that infamous massacre of the Vietnam War to the attention of the American public and the world, Ron was clearly born to be a writer. At just 23, Ridenhour explained his motivation:

“Exactly what did, in fact, occur in the village of “Pinkville” [i.e., My Lai] in March 1968 I do not know for certain, but I am convinced that it was something very black indeed. I am irrevocably persuaded that if you and I do truly believe in the principles of justice—and the equality of every man, however humble, before the law—that form the very backbone that this country is founded on, then we must press forward a widespread and public investigation of this matter with all our combined efforts. I think that it was Winston Churchill who once said, ‘A country without a conscience is a country without a soul, and a country without a soul is a country that cannot survive.’ I feel that I must take some positive action on this matter. I hope that you will launch an investigation immediately and keep me informed of your progress. If you cannot, then I don’t know what other course of action to take.”

My Lai was located within a pink area on their maps, and the nickname “Pinkville” was commonly used. My Lai, too, was the military’s misnomer for Son My village. The military’s official after-action report was pure propaganda. It also got plenty wrong, declaring My Lai a great victory against Viet Cong troops, 128 “enemy” dead and—tellingly—three weapons captured. For Ron, it was important to get it right.

What the Peers Report (the investigation into the My Lai massacre later conducted by Lt. Gen. William R. Peers), got right was this: on March 16, 1968, six weeks after the Tet offensive, Charlie Company of the Americal Division moved into a village south of Quang Ngai city, where they had been told they would find the 48th Viet Cong Main Force battalion. Instead of a concentration of V.C. forces, they found unarmed old men and women. They found children and babies. Led by 2nd Lt. William Calley, the men of C Company raped and burned and committed other crimes. They murdered 504 people. Directed by Calley, they lined up 174 people in an irrigation ditch and gunned them all down, Nazi-fashion. Nearby, B Company killed 97 (according to the My Lai Museum) in the hamlet of My Khe 4, a task that took all day.

Photo by Ron Haeberle

The only resistance came from some soldiers who refused to shoot, and from a helicopter crew led by Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson. Thompson tried to stop the carnage. Hugh landed his helicopter several times, rescuing survivors. At one point, he confronted Lt. William Calley and his men. He instructed his door gunner, Larry Coburn, to fire upon Calley and his men if they advanced on the villagers. Calley backed down.

Thompson reported what he’d seen to his superior officers. But there the matter rested. Hugh was quickly given the Distinguished Flying Cross for his “sound judgment,” which “greatly enhanced Vietnamese-American relations.” Thompson threw away medal and citation in disgust.

As Ron said, years later, in a talk at Tulane on the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary of the massacre, “The [four] command-and-control helicopters from the entire division [were] overhead all morning. . . . When [Charlie Company commander Captain Ernest] Medina went running through the village ordering people to stop shooting, guess what, they stopped shooting.” For Ron, My Lai was not an aberration but an operation, like many others.

When he learned of the massacre, Ron explained, “It’s hard for me to describe how ill-prepared I was for this role I found myself in. I felt compelled to act.” A corporal who had served as a helicopter gunner, after the massacre Ron was in a long-range reconnaissance patrol unit, where he served with men whom he knew from training, and he heard what they’d done and seen at My Lai. The role he now found himself in was to investigate the facts on his own, while still in the Army and still in Vietnam—an incredibly heroic act.

Ridenhour later became a respected investigative journalist, returning to Vietnam as a reporter for Time to cover the Cambodian incursion. But the news of Ron’s My Lai letter preceded him, and he received death threats from soldiers.

Later, in 1987, Ron won the George Polk Award for Investigative Journalism for a year-long investigation of a New Orleans tax scandal. He died suddenly in 1998 at the age of 52. At the time of his death, he was working on a piece for the London Review of Books, had co-produced a story on militias for NBC’s Dateline, and had just delivered a series of lectures commemorating the thirtieth anniversary of My Lai. You can watch his last talk, just weeks before his death, here.

I got to know Ron when I invited him to my course on the Literature of the Vietnam War at Tulane. Every semester, he’d come in and blow the students away with his mesmerizing and heartbreaking story. For Ron and others like him, including Jonathan Schell, the revered author of The Village of Ben Suc, My Lai was no aberration. It was a part of a pattern of wartime acts of butchery, a key strategy in the military’s counterinsurgency tool kit—to destroy, in Mao’s metaphor, the sea in which the guerillas swam, by destroying whole villages.

For Ron, My Lai mattered because that strategy continues to be used in our wars against insurgencies. For Ron, not to speak up was to be complicit in murders carried out in our name.

Here’s an excerpt from his last talk:

“Why does it matter today? I think it matters today in part because it wasn’t the last time this happened. It wasn’t the last time it happened in Vietnam. It wasn’t the last time this happened in the world. If you look at Central America, for instance, there were literally hundreds of My Lai-like massacres during the decade of the 80s, when we were deeply involved there and in which the only components of those wars that were not American provided and planned-for were the bodies of the people who pulled triggers. Everything else was ours. It was our strategy. It was our money. It was our training. It was our supplies, our guns, our bullets. The pattern is really quite astonishing if you look at it. By 1983 the Guatemalan army was admitting that they had committed in just the last two years the massacres of 662 Indian villages. In El Salvador the Salvadoran army was adopting the same pattern of counterinsurgency. . . El Mezote is the most famous of those, 764 people were murdered by El Salvadoran army, the Atlácatl Battalion, on December 8th, 1981. . . .

“Why should we remember it? Because it was the nature of the war that we fought. More importantly it was the nature of the wars that we then fostered in Central America.”

Ron didn’t survive to bear witness to the transformation of this core counterinsurgency tactic into our long-distance drone and cruise missile wars. I can hear him ranting now.

Nonetheless, why did I, an English teacher trained in the Romantic poets, teach such a course? Vietnam was the transformative experience of my generation, and for many of us there was the impulse to return and try to make sense of that trauma. I had been a draft resister, a participant in Moratoria Marches during my time at American University, and once was tear-gassed for protesting at the Watergate against its infamous resident, Defense Secretary Robert J. McNamara, a few years before the complex became the infamous site of Nixon’s criminality.

But more telling, my brother had been a medic in the war. Medics, we know, saw some serious shit. But I never heard about any of it from Jerry. We’d never had a close relationship—two children of divorce; two latchkey kids vying for their mother’s attention. If I heard about anything, it was about Jerry’s legendary poker games. But Jerry was the kind of guy who would do anything for his buddies. I’m sure he heard a lot of hot lead whizzing over his head.

So when I started dipping into the literature coming out of war, I wasn’t surprised that veterans often didn’t speak of their service. They felt that no one was listening, they felt rejected, so why talk about it? And if they chose to speak about some of the lines they were asked to cross, who would understand? The novelists, poets, and memoirists we read in my classes were the exception. They spoke for their brothers- and sisters-in-arms who couldn’t find their voices.

My course was an effort to listen and to build an audience for veterans of that war. When I moved from Tulane to the New School for Social Research in 2003, my syllabus began to include the literature from Vietnamese writers, here and in Vietnam itself, and from other American misadventures that followed, Iraq and Afghanistan.

In the years immediately following 9/11, many people who spoke out against intervention in Iraq on the grounds that the Bush administration was concocting claims about weapons of mass destruction and other false rationales were ostracized and punished. Together with Hamilton Fish, the editor of this journal, and inspired by Jonathan Schell, I co-founded the Ridenhour Prizes to recognize those who persevere in acts of truth-telling that protect the public interest, promote social justice, or illuminate a more just vision of society. These prizes have been my way over the years to continue the effort to create a listenership for whistleblowers and other truth-tellers. They want to say and for us to hear: listen to what I felt I had to do or be complicit in. The Ridenhour Prizes have been a way to say, We hear you.

And so there is a through line from the Vietnam War era to the annual prizes we give in Ron’s name. We try to find ways of bringing Ron the whistleblower into the room even to this day. We set the bar as high as we could with our first Courage Prize winner, Dan Ellsberg, the author of the Pentagon Papers and the definitive whistleblower of his generation (sadly, Dan died in 2023 at 93). The following year, we honored a legendary journalist, Seymour Hersh, who won the Pulitzer for his syndicated pieces on the My Lai massacre (substantially informed by conversations with Ron). We gave a special prize to Nick Turse when he published Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam, a brilliant interrogation of history that confirmed Ron’s deeply held belief that My Lai was one of many such abuses of military power through the years of that agonizing war.

Ambassador Joe Wilson and Dan Ellsberg, the first Truth-teller and Courage Prize winners.

There were other prizewinners whose truth-telling spoke to what’s been called the long 1960s, which ended sometime around the end of the war in Vietnam. Heather Ann Thompson received the Ridenhour Book Prize for her Pulitzer Prize–winning Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. Seth Rosenfeld explored the dark side of the deep state in Subversives: The FBI’s War on Student Radicals, and Reagan’s Rise to Power. Emma Pildes received the documentary prize for The Janes, about an early 1970s underground service for women seeking safe, affordable, illegal abortions. John Lewis, a catalyst of the Civil Rights marches, won the Courage Prize for his long challenge to us to make “good trouble.” Fritz Schwarz, chief counsel of the Church Committee, formed in 1975 in the wake of the Watergate scandal to investigate illegal intelligence gathering by federal agencies, including the CIA, the FBI, and the NSA, also won the Courage Prize. So too did Denis Hayes, for founding Earth Day in 1970. Add to that remarkable roster so many other notably courageous recipients, from Gloria Steinem and Bill Moyers to Jimmy Carter.

But if many of the prizes celebrated our winners’ work during the long 1960s, others have represented the many links from the new challenges that emerged during the war to our present troubles. James Hansen and the late Rick Piltz both won for their important work on the science of climate change, which administrations either ignored or, in Piltz’s case, distorted, when George W. Bush’s White House changed his data. Ambassador Joe Wilson pushed back against the Bush administration’s lies about yellowcake uranium that helped grease our way into the Iraq War. Edward Snowden and Laura Poitras broke the cone of silence about covert intelligence. Tarana Burke helped inspire the #MeToo movement. Carmen Yulín Cruz Soto, the mayor of San Juan, Puerto Rico, won for speaking out after Hurricane Maria and accusing Donald Trump and his administration of “killing us with inefficiency.” When, during the first Trump administration, the government was shut down, Spanish-born restaurateur José Andres, in the passionate spirit of duende, set up his World Central Kitchen to feed federal employees in front of the new Trump Hotel. Jamie Raskin, U.S. representative for Maryland’s 8th congressional district, served as lead House manager in the second Senate impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump, which ended with a 57–43 vote to convict Trump for inciting a violent insurrection against the Constitution to overthrow the 2020 presidential election. Raskin of course also served on the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the U.S. Capitol, and is now leading the effort to “debunk and refute MAGA propaganda and disinformation.”

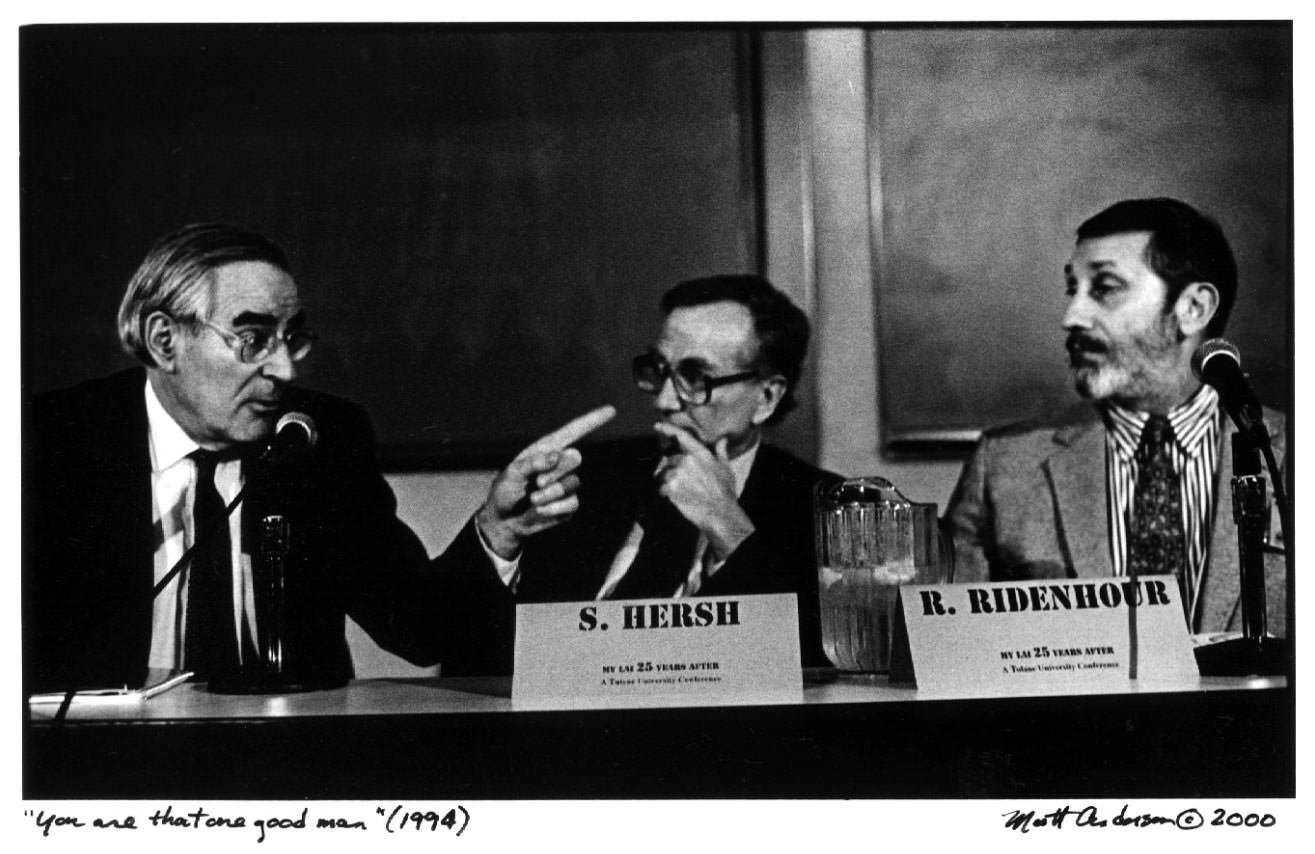

These and the dozens of other Ridenhour Prize recipients have perpetuated truth-telling and honored Ron’s memory. Perhaps the person who summed up Ron’s character and role in history best was David Halberstam, author of The Best and the Brightest. I had the privilege of introducing Ron Ridenhour to Halberstam at the twenty-fifth My Lai anniversary conference, held in New Orleans. They were two of a kind, both willing to speak truth to power, both ready to touch and to change history by doing so.

During the journalism panel at that conference, Halberstam pointed past Sy Hersh toward Ron as he recounted Robert Kennedy’s favorite quote from Emerson, that “‘if one good man plant himself upon his conscience, the whole world will come round.’ Ron, you are that one good man.”

Let me close with another reason for my tale of origins. I realized only recently all that Ron meant to me. Yes, he was a great friend and someone I could look up to, someone who touched history. But only recently have I realized he was the big brother I longed for.

Let us keep Ron’s memory and the animating spirit of these prizes alive.

A former adjunct professor of English, Randy Fertel taught Literature and the Experience of the Vietnam War for many years at Tulane and the New School for Social Research. He codirected Tulane’s 1994 international conference on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the My Lai massacre. Fertel is co-founder with Hamilton Fish of the Ridenhour Prizes for Courageous Truth-Telling.

Fertel is the author of three books, Winging It: Improv’s Power and Peril in the Time of Trump (Spring, 2024), A Taste for Chaos: The Art of Literary Improvisation (Spring, 2015), and The Gorilla Man and the Empress of Steak: A New Orleans Family Memoir (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2011) .

0 Comments