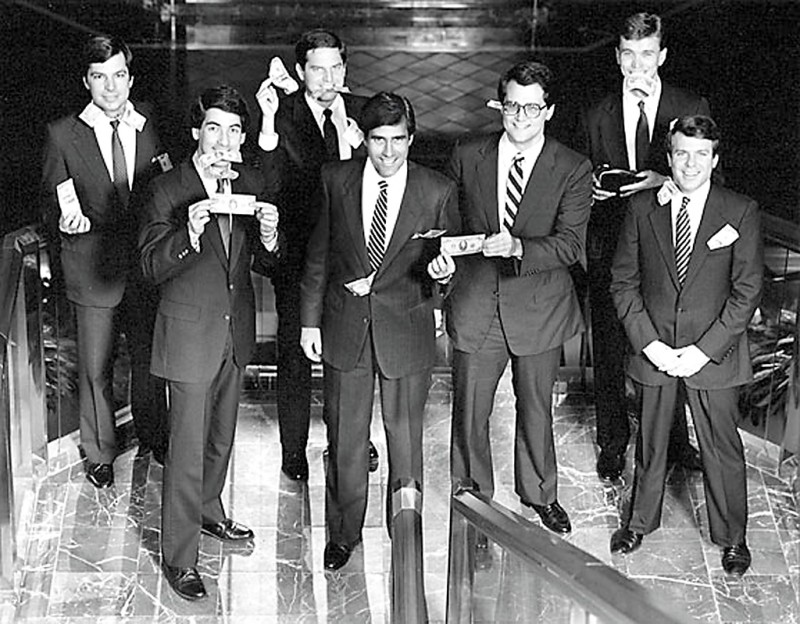

(Bain Capital is now famous for being founded by former Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney, center, whose estimated worth is $250 million. Bain Capital is one of 10 private-equity firms defending itself in a civil case that alleges they conspired to defraud investors. This photo is from 1984. Source: WP)

Private equity is poised to embark on a new era of leveraged buyouts to rival those of the late 1980s and mid-2000s. Financiers once toppled corporate giants like RJR Nabisco and and Harrah’s, and devoured hundreds of small companies. As Bain & Co. observed in its 2013 report on private equity:

The hunger for yield and the rapid erosion of the “refinancing cliff” have made the debt markets more buoyant than they have been in many years. Current leverage multiples rival those at the peak of 2007, and the cost of debt is near record lows.

In other words, it’s cheap to borrow money needed to launch raids. There’s “dry powder” in the kegs of the investment houses, as they say, idle money that’s in search of bigger returns than what’s possible in the stock and bond markets. Another era of buyouts would result in all the carnage associated with private equity — mass layoffs, asset stripping of debt-saddled companies, massive tax avoidance schemes, greater wealth inequality, and so on.

| A little known case against the world’s biggest buyout shops is heading to trial and the outcome could cost the world’s most elite financiers billions and billions. |

Private equity left behind a lot of wounded and dead in the wake of the two previous blitzkriegs. Most victims were and are powerless to prevent a return of the money men and nothing has changed under the law, or in politics, over the past 20 years to prevent a third debt-drunken buyout binge.

There are some, however, who are attacking private equity’s privilege and power.

Members only

In late 2007, the city pensions of Detroit and Omaha, together with individual investors, filed a moonshot of a class-action lawsuit in federal court in Massachusetts against 10 of the largest private equity firms.

The case is known as Dahl v. Bain.

Kirk Dahl, a Michigan doctor who now has the distinction of having his name legally headlined in one of the largest anti-trust lawsuits in history, says he was cheated in several buyout deals. Bain is none other than Mitt Romney’s former buyout powerhouse.

The plaintiffs allege that the biggest private-equity firms conspired to depress share prices of corporations that were targeted in the mid-2000s buyout boom. Plaintiffs claim the biggest firms — TPG, KKR, Blackstone, Apollo, Bain, Carlyle, Providence Equity Partners, Silver Lake, Thomas H. Lee, and a Goldman Sachs subsidiary— chose to abide by “club etiquette” to suppress outside competition for the biggest takeovers. “Club etiquette” is a phrase used in an internal e-mail to describe the conspiracy’s tenor. Think men’s club, where testosterone drives business acumen as much as computer models and due diligence.

Club etiquette entailed a mostly unspoken agreement not to “jump” one another’s deals with competing bids, but instead to bid together so as to spread around the lucrative profits to be made from buyouts. These profits were higher thanks to the discounted share prices private equity players paid due to the fact that there was no significant competition from the handful of other firms large enough to mount multi-billion dollar raids on mega-cap companies.

The alleged conspiracy was possible because the planet-straddling world of private equity is quite small at the top. Only a few dozen firms have the necessary equity and can borrow the staggering sums of money needed to take multi-billion dollar companies private. These men, virtually all of them white men who live around New York, Boston, and San Francisco, fly in their private jets to the same private island resorts and global destinations of the luxury elite. They invest in one another’s funds and co-own sports teams as hobbies. They call one another at all hours to chat about business deals and ping one another with pithy e-mails filled with obscure acronyms and friendly nicknames. They play in the same elite social clubs and dine together. They send their children to the same top private schools. You get the idea.

This secret market manipulation meant that shareholders of raided companies received less for their stock. Because institutional investors, including pensions, mutual funds, 401Ks, and other savings funds, own the largest stakes in most publicly traded corporations, an alleged conspiracy to depress share prices in buyouts cheated potentially millions of retirees and families. At stake in the 17 buyout deals at the heart of Dahl v. Bain are hundreds of billions of dollars.

The secrets of ‘club etiquette’

Between 2008 and 2012, the plaintiffs weathered a barrage of motions to delay and dismiss the case. “We’ve had rounds of motions to dismiss,” Christopher Burke, an antitrust litigators, told me. Burke is a lawyer with the San Diego-based Scott & Scott law firm. He said the private equity firms “have just sprayed money at the process.”

“Every white-shoe firm you can imagine is on their side. These are very rich people — billionaires. They don’t like to be held accountable or garner unwanted publicity. They are the beneficiaries of a tax system that subsidizes what they do, loading up companies with debt, making interest payments on that debt, to obtain profits for themselves and their investors.”

| Did Wall Street’s biggest private-equity firms, including Mitt Romney’s Bain, conspire to depress stock prices of corporations they bought out in the mid-2000s? |

Burke and his colleagues survived motions to dismiss and reached the discovery phase in May of 2010. Discovery in this case has generated an unprecedented look into the inner-workings and deliberations of an elite world. The defendants coughed up more than 5.6 million documents and the masters of the universe were forced to submit to depositions. But their lawyers succeeded in sealing nearly all of the evidence generated by the case, arguing that disclosure would reveal proprietary trade secrets.

“Keep in mind they’ve shared all this info with one another,” Burke said. “Now they say it’s competitive secrets? The normal practice for them is to share information, so it’s a little disingenuous for them to argue this.”

The only glimpses we have are references in the amended complaints (especially the case’s 5th Amended Complaint) and in court transcripts (most recently Dec. 18, 2012, and Dec. 19, 2012). Even this almost never saw the light of day. Lawyers representing The New York Times had to to unseal the 5th Amended Complaint.

Among the more incriminating bits of information are statements made by dealmakers in e-mails with one another. Illustrative of their “club etiquette” is an exchange between Blackstone’s Hamilton James and KKR’s George Roberts after Blackstone agreed not to compete for the buyout of Hospital Corporation of America for $21 billion in 2006. James wrote:

“Thx for the call George. I talked to Henry [Kravis] Friday night and he was good enough to call Steve [Schwarzman] Saturday. We would much rather work with you guys than against you. Together we can be unstoppable but in opposition we can cost each other a lot of money.”

Hamilton James is worth about $1.1 billion; George Roberts about $4.1 billion. These men made a lot of this cash during the alleged conspiratorial era under examination by the court in Dahl v. Bain.

At stake, hundreds of billions of dollars

Bringing their case under the Sherman Act’s antitrust provisions has been challenging for the plaintiffs. Proving a conspiracy among powerful finance capitalists is made more difficult because their money is sheltered in limited partnerships and private corporations, many of them incorporated offshore, and therefore secret. Without a smoking gun, the plaintiffs in antitrust cases must build their argument around the totality of evidence, statements, and broader context.

In March, the plaintiffs prevailed against a motion for summary judgement in which the defendants sought to throw out the entire case. The judge ruled that there is sufficient evidence to infer the presence of an over-arching conspiracy among the private equity firms to suppress share prices by not “jumping” one another’s deals. The judge further ruled that with respect to the takeover of HCA, the evidence is strong enough to proceed with an individual count of conspiracy and antitrust activity.

| Judge: The evidence, taken all together, does suggest a vast Wall Street conspiracy. |

According to Judge Edward F. Harrington:

The evidence establishes that each Remaining HCA Defendant showed interest in the HCA transaction, but promptly “stepped down” from making a topping bid within 48 hours of the commencement of the fifty-day “go-shop” period. The evidence further shows that the Remaining HCA Defendants communicated their decision to “step down” on HCA to KKR or Bain within ninety-six hours of the commencement of the “go shop” period and subsequently lamented having forgone a potentially lucrative deal. While this uniform conduct on the part of the Remaining HCA Defendants would not, on its own, support an inference of a conspiracy as to HCA, in combination with at least two statements made by executives of the Remaining HCA Defendants, it does support such an inference.

Those admissions in a couple of e-mails buried in the prolific correspondences between the firms, tipped the scale. In one, a top a executive at Carlyle remarked matter-of-factly that “KKR asked the industry to step down on HCA.” A second statement from Blackstone described how KKR abided by “club etiquette” in backing away from Blackstone’s bid for another company: “Henry Kravis [of KKR] just called to say congratulations and that they were standing down because he had told me before they would not jump a signed deal of ours.”

“In the HCA count,” explained Burke, “Bain and KKR and Merrill Lynch got together and got an agreement from the rest of the major private equity firms to not bid on HCA.”

The plaintiffs may have caught the private equity big shots red-handed in suppressing competition on the HCA buyout. It’s going to be tougher for them to prove a broader overarching conspiracy among all 10 private equity firms to allocate the broader market for mega-cap buyouts in the mid-2000s. The case will surely generate more juicy inside information on the operations of private equity, and we’ll be following it.

Darwin Bondgraham is a sociologist and journalist who writes about political economy. His writing has appeared in Counterpunch, Truthout, Z Magazine and others. Follow him @DarwinBondGraham and @WashSpec.

0 Comments