This article is published in partnership with the The Center for Media and Democracy.

The appearance of Teamsters president Sean O’Brien at the Republican convention in July was the most public salvo yet in an otherwise quiet conservative debate: whether, and how, to embrace labor, and what to do about the union question.

O’Brien’s unusual appearance prompted outrage from all corners of the outspokenly pro-labor establishment: the White House, where President Biden has been applauded as the most pro-labor president since FDR; labor unions, with UAW President Shawn Fain quickly denouncing the move; and the progressive Left, with congressional Democrats and other labor union leaders criticizing his appearance as a betrayal. And the speech has prompted internal division within the Teamsters at the highest ranks.

Yet O’Brien’s move has attracted the attention of commentators from both sides of the political spectrum who see it as a bellwether. It is what conservative commentator Sohrab Ahmari has called a “brave gambit” and veteran labor reporter Steven Greenhouse dubbed a “huge gamble.”

“A glacier of hostility has divided the GOP from organized labor for two generations,” Ahmari wrote in Compact. But the Teamsters president “took a pickaxe to that glacier” by speaking at the RNC.

Ahmari attributes the rise of this strain of pro-labor, anti-union conservatism to Senator Josh Hawley (R-MO), a MAGA firebrand who has come out as perhaps the lone GOP senator to oppose right to work legislation, the anti-union laws on the books in 28 states.

Championing labor has long been the purview of progressives, despite recent rhetoric from Republicans who claim to represent working class America. The trend has yet to emerge in any substantive way; for now, conservatives have almost uniformly wielded their power to crush unions and weaken social policies that help working families.

During Trump’s term in office, his appointments to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) worked to roll back workplace protections (such as holding employers responsible for labor violations by subcontractors) and chill workers’ efforts to organize. His administration rescinded regulations that protected workers from pesticide exposure; made it harder for the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to inspect worksites like coal mines, where workers develop silicosis; eroded OSHA’s advisory boards; and, before a union-led lawsuit rendered the proposed new guidelines moot, uncapped pork plant line speeds. Trump’s appointees to the Supreme Court ensured the death of closed-shop unions and stymied farm worker organizing. In 2021, all but five House Republicans voted against the Protect the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, which would make it significantly easier for workers to organize unions.

And, just weeks after the convention, Trump told Elon Musk in an interview that striking workers should be fired — a violation of federal labor law — prompting the UAW to file unfair labor practice charges.

O’Brien, too, slammed Trump for his remarks, calling his ideas “economic terrorism.”

In Trump’s RNC speech, he called for UAW president Fain to be fired.

The GOP’s Newfound Worker Whisperers

Yet some Republicans — in power and those who speak to it — are bucking that anti-worker trend, or are claiming to in their quest for populist appeal.

The most prominent Republican remaking his brand as a champion of labor is Hawley, as part of his 2024 reelection bid — despite the two-term senator’s longstanding opposition to pro-labor policies and despite his Democratic opponent receiving the majority of Missouri’s labor endorsements.

In a recent essay, “The Promise of Pro-Labor Conservatism,” Hawley laid out his vision for this movement. “Thousands of Americans have voted to unionize in elections but can never get a contract done, often due to corporate tricks. How can we let that stand?” he wrote. “Unions are a vital piece of the fabric of a nation that depends on working people.”

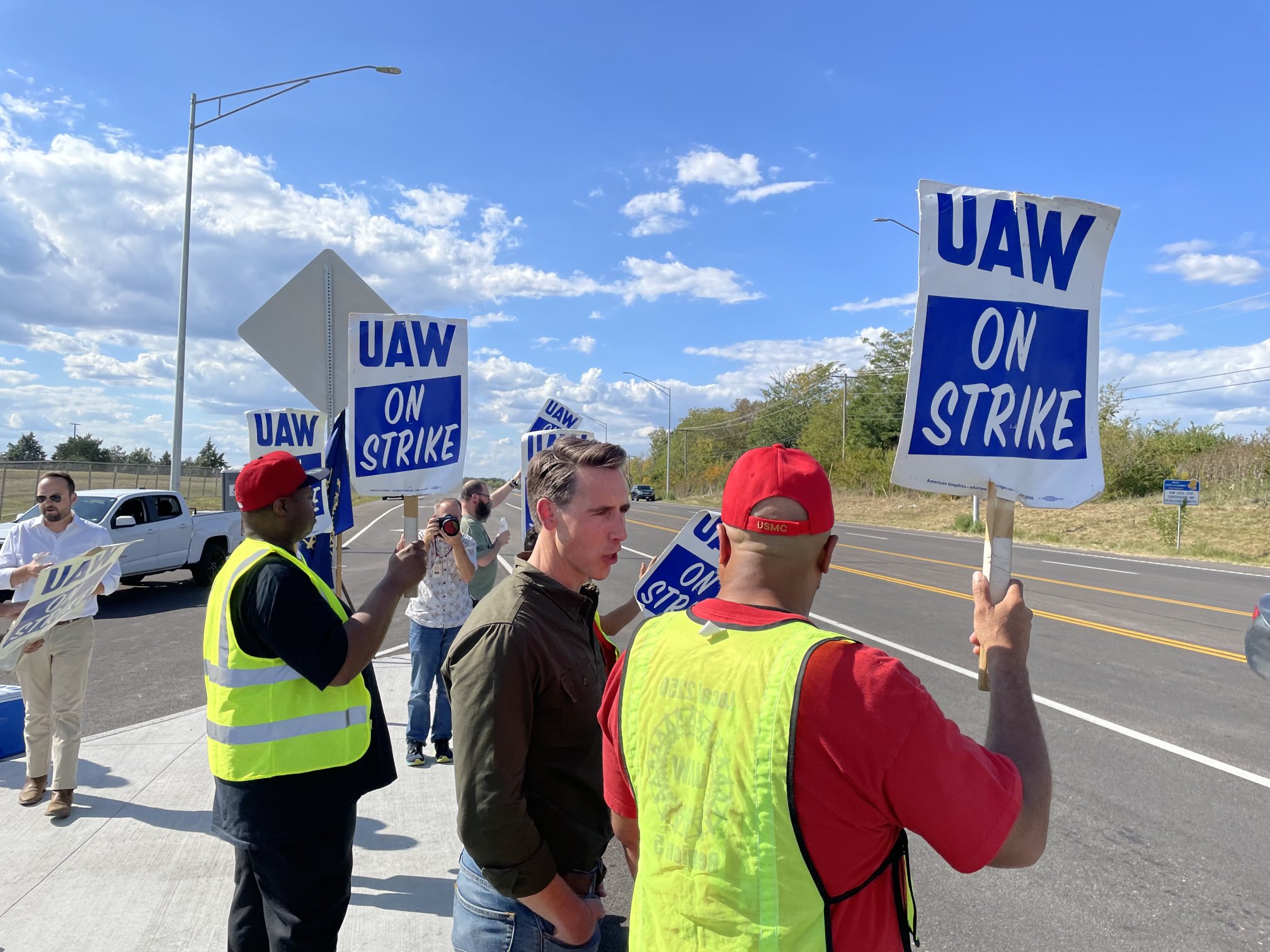

But Hawley’s staunch anti-labor track record and his apparent politicking have cast doubt on how serious his and the GOP’s embrace of labor really is. He received ample criticism after walking a picket line with striking UAW auto workers in October 2023, with one local union president calling his presence “deplorable, disingenuous, and disgusting” and the state AFL-CIO president saying Hawley was “a fraud who doesn’t give a damn about Missouri workers and only shows up when the camera flashes.”

Just a few years prior, Hawley opposed a minimum wage increase and supported an ultimately unsuccessful right-to-work ballot measure, saying “nobody should be forced to pay union dues.” As Missouri’s attorney general, he successfully blocked a federal overtime pay expansion; as a result, 237,000 Missourians lost overtime pay protections, which cost these workers an estimated $27 million a year.

Despite all this, in his new role as a labor champion Hawley is opposing national right to work laws, a stance that has drawn the ire of conservative commentators.

After attending the UAW rally, Hawley lost the endorsement of the local union chapter. “Josh Hawley calling himself pro-worker is a total joke,” said Fred Jamison, president of the UAW Region 4 Midwest States Cap Council. “There is only one candidate in this U.S. Senate race who has earned the trust of Missouri autoworkers, and that’s Lucas Kunce.”

Another ostensibly pro-worker Republican is Trump’s vice presidential pick, Senator JD Vance (R-OH), whose involvement in billionaire Peter Thiel’s venture capital firm did little to temper his reputation as the working class populist he claims to be in his memoir Hillbilly Elegy.

Yet after just two years in the Senate, and despite his contradictory record on labor, the Yale Law alum appears to have scared centrist Republicans. The business community sees his nomination as an existential threat to the status quo, with some of the senator’s policy stances amounting to “an American CEO’s worst nightmare.”

Vance’s speech at the RNC offered a case in point. “We need a leader who’s not in the pocket of big business,” he said, “but answers to the working man, union and nonunion alike.”

Pro-Worker in Name Only

Despite Hawley’s proclamations, many others on the Right who crow about pro-worker policies are really just reframing anti-union policies.

The message that these organizations and legal crusaders push is simple: unions, which conservatives accuse of sucking away wages to fund woke, left-wing causes, are the workers’ biggest enemy. Therefore, the most pro-worker policy is to get rid of unions altogether.

These anti-union organizations are legion, and all make use of this basic formula.

The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), the right-wing bill mill responsible for drafting model bills and farming them out to Republican state lawmakers, belongs at the top of the list. Though ALEC brands itself as a decades-long champion of “worker freedom,” it has been responsible for a wide variety of assaults on workers and unions, from undermining efforts to organize to kneecapping the ability of local governments to implement pro-labor laws such as higher minimum wages. ALEC pedals model bills that prohibit automatic dues deductions from paychecks, mandate high membership thresholds, and trigger required decertification, among other anti-labor measures. ALEC provided the “intellectual ammunition” for former Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker’s historic attacks on public sector unions more than a decade ago, as he celebrates in a recent ALEC promotional video.

The Freedom Foundation, which held a conference this summer to teach teachers to bust their own unions, is one of the most aggressive anti-union outfits, regularly running “opt-out” campaigns that pressure union members to stop paying union dues. It claims as its guiding principle the liberation of “public employees from political exploitation.” The National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation says it works to “eliminate coercive union power and compulsory unionism abuses.” The League of American Workers decries that unions with “corrupt leadership” have been “captured by The Democrat Party and a cringe radical agenda.” And the Center for Worker Freedom, a project of Americans for Tax Reform, focuses on “warning the public about the causes and consequences of unionization.”

Most of these organizations are affiliated with the State Policy Network (SPN), an interconnected group of think tanks that helps to coordinate anti-labor policies and circulates a union-busting toolkit.

These coordinated attacks — bankrolled by billionaires — largely culminated in the 2018 Janus Supreme Court decision, which ruled that public employees are not required to pay for the costs of union representation.

Intellectual Foundation and Champions

To those who primarily associate conservatism with fiscal restraint and unlimited free enterprise, the emergence of a movement bucking that trend may come as a surprise.

There is, in fact, a substantial lineage of social conservatism that identifies the free market as being one of the major causes of social decay, and considers labor, trade, and immigration policies as a means of tightening the labor market so that nuclear families can be supported on a single income. At the core of this ideology — which owes much to Catholic social teaching and is rooted in faith and traditional gender norms — is the idea that policies aimed at supporting American families should be a national priority.

This means that certain conservatives focus on supporting per-child tax credits, enacting paid family leave policies, and even promoting sabbatarian laws that provide workers with overtime pay for working during the Christian Sabbath.

Most recently, Patrick Deneen, a political science professor at Notre Dame, has encapsulated this worldview for mainstream audiences in his book Why Liberalism Failed.

This “common sense conservatism,” as he and others — including Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) — call it, “is pro worker, favoring policies that protect jobs and industries within nations.” It also calls for “more controlled immigration policies, supporting private-sector unions, and calling upon the power of the state to secure social safety nets targeted at supporting middle-class security,” Deneen wrote in his most recent book, Regime Change.

Like many of the current proponents of common sense conservatism, Deneen is a devout Catholic, as is Vance, who converted in 2019, and Rubio, who cites the church’s acknowledgement of “the essential role of labor unions” — a trend echoed by the New Right’s young intellectuals.

(Libertarian critics deride this call for government interventionism as “will-to-power conservatism” and “big government conservatism.”)

American Compass, which has recently drawn attention due to its ties to Vance, and its founder, Oren Cass, are providing the policy framework for this idea. They have been in the spotlight in the past few years, and increasingly so since O’Brien’s appearance at the RNC.

Cass — who Vance has referred to as a friend — applauded Vance’s speech as evidence of the rise of “actual conservatism,” claiming that “the libertarian and neoconservative appendages that have so badly disfigured conservatism are being excised.”

“America’s labor movement, especially in the private sector, has faded toward irrelevance and become focused primarily on political activism,” American Compass claims — a trend the organization would like to change.

“Rather than cheer the demise of a once-valuable institution, conservatives should seek reform and reinvigoration of the laws that govern organizing and collective bargaining,” American Compass proclaimed in an inaugural 2020 open letter, which Vance signed while he was a fellow at the pro-free market American Enterprise Institute.

Yet, as an early commentator pointed out, the proposals made by American Compass can be very light on specifics, and often favor “less adversarial” options like work councils and employee stock ownership programs (ESOPs) over worker-led unions. For example, Vance and Rubio recently reintroduced the Teamwork for Employees and Managers Act (TEAM) Act, a business-friendly labor reform bill that was originally vetoed by President Bill Clinton in 1995 and which American Compass is attempting to resuscitate. The bill — which was quashed due to an uproar from organized labor — would effectively permit company-run unions, which were outlawed in the 1930s.

The organization’s first letter itself is a contradiction in terms: other signatories include a former partner at the notoriously anti-worker law firm Gibson Dunn, which has represented Amazon in its disputes with the Amazon Labor Union and defended Walmart when 1.5 million current and former employees accused it of gender discrimination.

Other signatories include Jonathan Berry, a former official in Trump’s justice and labor departments who authored the labor section of the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025; representatives from the anti-LGBTQ think tank the Institute for Family Studies; and a senior counsel from PR Policy Associates who testified against the PRO Act on behalf of a group that has campaigned against the constitutionality of the NLRB.

In his interview with Ahmari, O’Brien conceded that although he made a splash by speaking at the RNC, the Teamsters’ flirtation with the GOP is in its “infant stage.”

As suggested by Noam Scheiber, the nascent vision outlined by pro-labor conservatives will undoubtedly appeal to some workers. For anyone concerned about the American legacy of coupling workplace justice with progressive politics, these developments should be watched closely.

Juliana Broad is a writer and researcher who works on issues related to labor, science, and democracy. With the Center for Media and Democracy, she focuses on the corporate interest groups coordinating attacks on workers’ rights, campaign finance transparency, and access to reproductive healthcare, among other issues. She has also worked with unions as a labor organizer and strategic researcher in a variety of sectors, including higher education, healthcare, and property services.

0 Comments