Each of the three judges on the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals panel that upheld Wisconsin’s voter ID law last Friday bore the Federalist Society seal of approval when they were appointed to the federal bench.

So the decision to toss District Judge Lynn Aldeman’s 70-page opinion that found Wisconsin’s voter ID law in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act was a done deal when the three jurists were randomly assigned to hear the case.

The Federalist Society is a right-wing fellowship of lawyers that also serves as a farm team for Republican nominees to the federal bench.

The rank political quality of the Wisconsin decision is hard to ignore.

In five paragraphs, the three Republican appellate court judges disposed of an expansive opinion written four months earlier by a Democratic appointee to the federal bench, issuing their decision immediately after oral arguments. And seven weeks before the midterm election date.

Judge Aldeman, a Bill Clinton appointee and former Wisconsin legislator, had concluded that 300,000 eligible voters in the state did not have the driver licenses required to cast their vote and could be denied access to the polls. He also wrote that Wisconsin’s voter-ID law was passed despite the absence of any record of voter impersonation in Wisconsin.

The appeals court judges were not persuaded, ruling that the voter ID law will take immediate affect.

Speaking at the 2013 Federalist Society’s National Lawyers Convention in Washington, Walker described the Wisconsin appellate judge as “one of our favorite jurists.”

Richard Hasen, a University of California, Irvine, professor and election law expert, described the appeals court decision as the “height of irresponsibility which did not even bother to consider or mention the difficulty of rolling out the voter ID when the voting process had already started.” (Eleven thousand absentee ballots have already been mailed out.)

“Court orders affecting elections, especially conflicting orders, can themselves result in voter confusion and consequent incentive to remain away from the polls. As an election draws closer, that risk will increase,” Hasen wrote, quoting a Supreme Court decision.

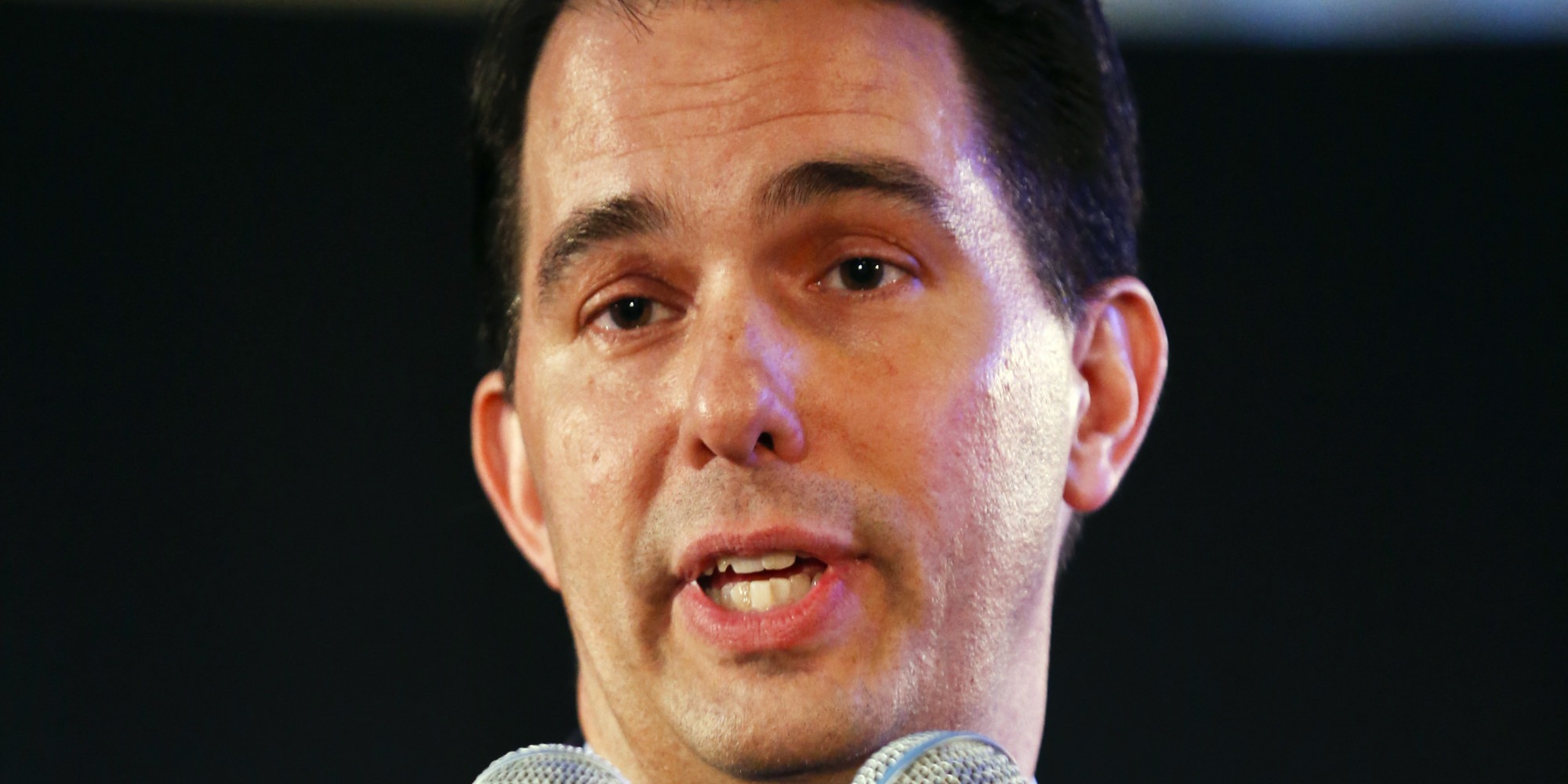

Aldeman had consolidated two cases challenging the law. As it turns out, the defendant in one of the cases is Scott Walker, “in his official capacity of Governor of State of Wisconsin.”

Walker is in a tight race with Democratic challenger Mary Burke and stands to benefit from a law that Adleman concluded will suppress the Democratic vote in November.

Was the Seventh Circuit panel in the tank for Walker?

A year ago, before an investigation into illegal campaign activity turned Governor Walker into damaged goods, he was prematurely appointing Seventh Court of Appeals Judge Diane Sykes to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Speaking at the 2013 Federalist Society’s National Lawyers Convention in Washington, Walker described the Wisconsin appellate judge as “one of our favorite jurists.”

As a state legislator, Walker said, he had backed her appointment to the State Supreme Court in 1999.

“If I ever got the chance to appoint you to something in the future, I’d be inclined to do that,” he said to Judge Sykes, obliquely referring to his next gig in the Oval Office.

Sykes, a G.W. Bush appointee, is the youngest of three Federalist Society judges on the panel that reinstated the voter-ID law. Frank Easterbrook was appointed by Ronald Reagan. John Tinder, who had served as a member of a Federalist Society advisory committee and said in his Senate confirmation hearing that he was never actually a member, was another G. W. Bush appointee.

The judges cited the Supreme Court’s decision upholding Indiana’s voter ID law as a precedent that supported the Wisconsin law.

In 2005 Indiana passed the first voter-ID law in the nation. Georgia’s Republican legislature followed suit the same year. A lot has come to light since the Supreme Court upheld Indiana’s law by a 6-3 margin in 2007.

It was not known at the time that the Indiana law (and Georgia’s) was a cut-and-paste bill provided by the American Legislative Exchange Council, a cash-rich corporate advocacy group that passes itself off as an association of legislators. (Republican legislators join, corporations and trade associations provide the 98 percent of funding.)

Emmet Bondurant, an Atlanta lawyer who represented plaintiffs in an unsuccessful challenge of the Georgia law, told me he was led to believe that the bill was a response to a grassroots movement to deal with voter fraud.

“I wish I had known it was an ALEC bill when I filed our lawsuit,” Bondurant told me.

Unlike Indiana’s plaintiffs, Bondurant did extensive demographic research, which established that Georgia’s law bore most heavily on African Americans and other minorities. The record Bondurant developed convinced Federal District Judge Harold Murphy, who in 2005 enjoined Georgia’s voter ID law:

[T]he photo ID requirement makes the exercise of the fundamental right to vote extremely difficult for voters currently without acceptable forms of photo ID for whom obtaining a photo ID would be a hardship. Unfortunately, the photo ID requirement is most likely to prevent Georgia’s elderly, poor and African-American voters from voting. For those citizens, the character and magnitude of their injury—the loss of their right to vote—is undeniably demoralizing and extreme.

But Judge Murphy lifted his temporary restraining order after the Supreme Court upheld Indiana’s voter ID law. Bondurant suggested that Murphy, a Jimmy Carter appointee in his late eighties, was too deferential to the Supreme Court’s ruling on Indiana.

Seventh Court of Appeals Judge Diane Sykes

And the Supreme Court’s Indiana opinion hasn’t aged well.

It has been criticized by one of the appellate court judges who voted to uphold it and by one of the Supreme Court Justices who voted for it.

Appeals Court Judge Richard Posner, a widely published and accomplished conservative scholar, was one of the two judges on a three-judge appeals panel that voted 2-1 to uphold the Indiana law in 2006.

Posner was ambivalent at the time, observing that: “As far as anyone knows, no one in Indiana, and not many people elsewhere, are known to have been prosecuted for impersonating a registered voter.”

He’s no longer ambivalent.

“What has happened since is that more evidence has emerged that these voter ID laws are intended to disenfranchise Democrats,” Posner said in a July 2014 interview with the ABA Journal.

“That evidence either didn’t exist when [the Indiana Case] came before us or the lawyers didn’t present it to us. I should have done more looking, but I’m not sure the evidence actually existed at the time.”

And former Justice John Paul Stevens, the member of the 6-3 Supreme Court majority who wrote the Court’s Indiana opinion, has also backed away from his vote.

The voter ID litigation hasn’t fully run its course.

Plaintiffs in other states (the Texas law is currently in federal court in Corpus Christ), are challenging the laws under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Regardless of who prevails, the stakes are high enough that the decisions will be appealed.

The final word will rest with the United States Supreme Court, where Chief Justice John Roberts is also a member of the Federalist Society.

—Lou Dubose

Lou Dubose is the editor of The Washington Spectator.