More than 300 tribes from around the globe came together to unite against the Dakota Access Pipeline, a 1,172-mile pipeline slated to carry crude oil from the Bakken formation in North Dakota to storage facilities in Illinois. The first prayer camps were established in the spring by indigenous youth and by the end of summer, thousands of self-described Water Protectors had gathered on the banks of the Missouri River.

Their resistance is both novel and a perpetuation of history. While the scope of this tribal communion has never been seen before, the struggle for indigenous people seeking to protect and maintain their land has been carved deep into America’s past.

The $3.7 billion pipeline was originally slated to cross the Missouri River north of Bismarck, but was later rerouted to cross just 1500 feet upstream of the Standing Rock Reservation, through sacred territory originally set aside for the Sioux in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. The Missouri is the tribe’s primary source of drinking water, along with 17 million other Americans.

In response to the movement, the Morton County Sheriff’s Department along with various state and local law enforcement used militarized tactics against the Water Protectors, leading to numerous injuries and hospitalizations.

During President Obama’s last days in office, the Army Corps of Engineers denied the easement needed for the pipeline to cross the Missouri River. The agency pledged to consider alternative routes as it prepared to conduct a full Environmental Impact Statement, a process that would examine the environmental risks of a spill, as well as the tribe’s treaty rights. Less than a week after his inauguration, Donald Trump signed a memorandum ordering the Army Corps to review and approve the project. The EIS was annulled, pipeline construction has resumed, and the main Oceti Sakowin camp has been ordered to vacate by today.

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, along with several others, have vowed to fight the pipeline in court and have asked for people to join them in their march on Washington next month.

—M.C.

Dakota Access Pipeline construction and a tributary of the Missouri River, seen from the edges of camp.

The Missouri River is 12,000 years old. It springs from the Rocky Mountains and flows across the country before joining the Mississippi River to form the world’s fourth longest river system. For more than 9,000 years Native Americans have inhabited its banks. Lewis and Clarke used the river to navigate their 1804-06 expedition. In the 1940s, Congress ordered the construction of several dams along the Missouri just north of the Standing Rock Reservation, flooding their best lands and forcing hundreds to re-locate.

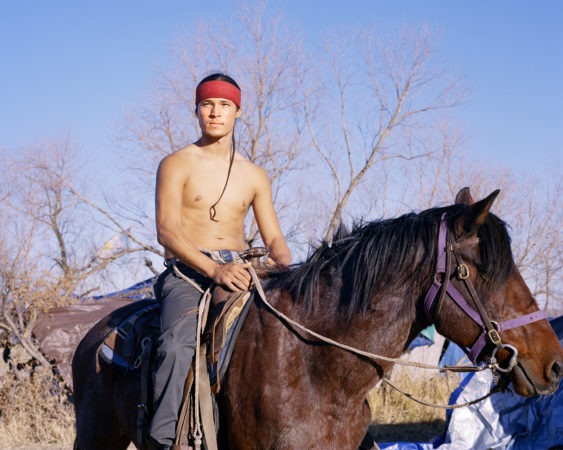

Elih Lizama, 24, of the Apache and Mayan tribes from Salinas, California.

Lizama is at the front of almost every direct action; some describe him as a frontliner. During a particularly brutal standoff with law enforcement on November 2, 2016 Lizama used his body as a shield to protect others from rubber bullets.

The youth began the movement when Jacilyn Charger and other indigenous youth ran a relay of 2,000 miles from Cannon Ball, North Dakota to Washington D.C. to deliver a petition in opposition to the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. The youth, in many ways, remain the core of the movement. During all organized actions they are continuously reminding the participants that they are there in peace and prayer.

Flag Row at dusk. Hundreds of flags representing the support of indigenous people from across the world line the main entrance into Oceti Sakowin Camp, located on the edge of the Standing Rock Reservation. At its peak, 10,000 Water Protectors were camping alongside the Missouri and Cannonball Rivers, they have worked to build a non-violent, highly organized community.

Lauren Howland, 21, a member of the International Indigenous Youth Council.

“I’m from Dulce, New Mexico, which is on the Jicarilla Apache Reservation, but the tribe I’m affiliated with is San Carlos Apache Nation, I’m also half Navajo. The mission of the International Indigenous Youth Council is to help fight back against environmental racism. That is one of our main goals, to stand in solidarity with those who choose to help and protect Mother Earth.”

Howland’s wrist was broken by a National Guardsman’s baton on October 22, 2016. She and other Water Protectors were attempting to reach pipeline construction sites when they were corralled by law enforcement. Fearing they were about to be arrested, Howland says she was trying to convince officers to let a young child leave the scene when an officer in military fatigues repeatedly struck her with his baton.

The Backwater Bridge on Highway 1806 has been the site of several clashes between Water Protectors and law enforcement. Burned vehicles remain from the police raid on Sacred Grounds Camp on October 27, 2016 where over 140 people were arrested.

Jacquelyn Cordova, 26, from Taos, New Mexico and a member of the International Indigenous Youth Council.

“It’s challenging to show up in the face of darkness with light. I don’t think the police officers are horrible people, they’re being controlled by the system and that’s been passed down through generations. They’ve acted on behalf of the darkness, for sure, but in no way is that attached to them at their core and who they are. I feel like the only way to connect with people is by being human with them . . . So they need to be taken care of too, and they need to be loved and not judged.”

On December 5, 2016 in a blizzard, with temperatures in the teens, and winds gusting over 45 mph, visibility reached a low of .25 miles as Water Protectors march to the Blackwater Bridge.

That evening the Water Protectors worked together to ensure everyone made it to a delegated warm space in the camps and on the reservation. Medics travelled throughout the camps performing wellness checks, and kept a keen eye on youth and the elders.

Thomas Tonatiuh Lopez, 24, Chicano and a member of the International Indigenous Youth Council.

On December 4, 2016 the Army Corp of Engineers announced it would not grant the easement needed for the Dakota Access Pipeline to cross under the Missouri river.

In response to the announcement Lopez explained, “Growing up as an indigenous person often you feel ignored, very isolated, unwanted, like if you and your people were to disappear everyone would just be happier. It can be really hard growing up thinking that

no one wants you around, everybody hates you, that you’re just a costume, you’re just a bedtime story, you’re just a figment of someone’s imagination. Not being identified as a human being, not being seen as a group of people. To see [the easement denial] was very empowering, to finally know that we took back our voice, we let the world know that we are here and we are not going anywhere.”

You can find a full version of this essay at Madeline’s website.

Madeline Cottingham is a New York-based photographer, dedicated to examining environmental and human rights issues. Her photography has taken her across the globe, from gold mines in Tanzania and the ruins of Hurricane Sandy, to the front lines of the natural gas revolution in Pennsylvania.

0 Comments