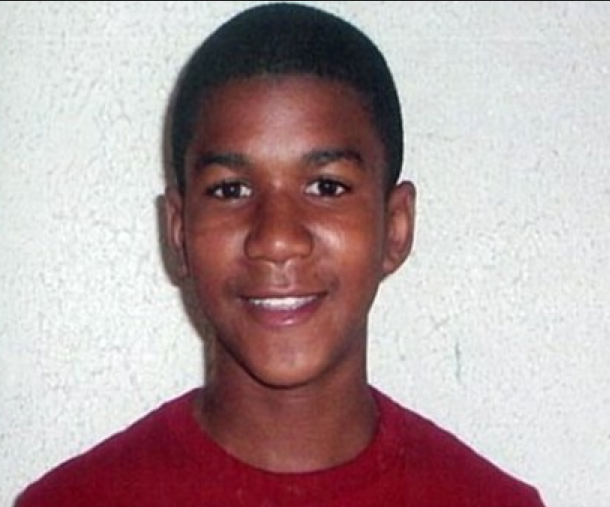

(Trayvon Martin | Source: news reports)

Black people are upset.

The killing of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman, and Zimmerman’s subsequent acquittal, are the most recent matches on a tinderbox of legitimate black anger and alienation in America today.

Black men and boys are feared, followed and frisked based solely on their appearance. Black unemployment is double that of white unemployment. Civil rights protections as fundamental as the Voting Rights Act face renewed attack. Meanwhile, we consciously and unconsciously fan the flames of persistent implicit bias and exclusion—and then blame black people for calling the fire department. Now is the time to hear the alarm bell and douse the flames.

| Negative attitudes toward blacks have increased by more than 50 percent since Barack Obama was elected. |

Black Americans know that we have made important strides on race in America. In 1961, my father—a black organic chemist—married my mother—a white graduate student in English literature. It wasn’t until 1966 that the Supreme Court struck down laws making their union illegal. Certainly that’s progress.

Yet the distance between races is vast, in part because blacks and whites live in different worlds.

The Pew Research Center reported that while only 28 percent of white Americans believe this country needs to discuss race in light of the Zimmerman acquittal, 78 percent of black Americans feel such inquiries are essential. Recognizing that Black America has a unique window into the broader inequalities and injustices that hurt us all, on July 30 the Democratic Caucus Policy Committee and the Congressional Black Caucus began hearings on race and justice in America. This was important for two reasons. It recognized that policymakers must consider how they should respond. And it made it clear that such injustice is not limited to Trayvon Martin.

On the eve of my testimony before the hearings, I received an e-mail from my cousin. She recalled a 23-year-old college student in Lexington, Kentucky, who was shot and killed in 2010 after getting out of his car to confront two other young men. The victim, Daniel Covington, was black. The state’s attorney declined to prosecute the shooter, who is white. News reports later made clear that someone in the shooter’s car hurled a racial epithet at Covington. News outlets did not report that Covington was dating the white ex-girlfriend of one of the two men he confronted on the night he died (information my cousin knew from her stepdaughters).

This happened eerily close to the anniversary of the birth of Emmett Till, the young black boy lynched in Mississippi in 1955 after allegedly whistling at a white woman. The Kentucky episode is just one of thousands of stories, big and small, that remind black people every day of the distance we as a nation still must travel to achieve full racial justice.

Black people are feared, judged and, yes, killed in America today for no legitimate reason. All too often, this discrimination and violence is fed by the unconscious associations we make about black people whom we don’t even know. While we frown on old-fashioned explicit bigotry, our laws have not kept pace with advances in our understanding of the neurocognitive underpinnings of “implicit bias.” Most of us behave based on stereotypes we do not even realize we are acting upon.

Black Americans with bachelor degrees have a harder time getting jobs than white Americans with bachelor degrees. One study of 1,500 New York City employers found that black job applicants with no criminal records did no better at getting a job than white job applicants with criminal records. College students are more likely to shoot a black man holding an object like a wallet than a white man. Teachers have unconscious and unfair low expectations of black students. And of course, the criminal justice system itself demonstrates a “shooter bias” in prosecutorial and judicial decision-making and jury verdicts. A 2012 Associated Press poll found that both conscious and unconscious negative attitudes toward blacks have increased, 51 percent and 56 percent respectively, since we elected our first black president in 2008.

We know that the fires of injustice are burning in black communities and individual hearts across this nation, fed not just by the legacies of the past but by the real discrimination of today. The only way to start to fix implicit bias is to acknowledge it, to refuse to let it hide in our unconscious, to work against those impulses and pursue policies and practices of equity.

And the only way to get there is to understand that black anger is real and justified—and to start talking about why.

Attorney Maya Wiley is a policy advocate and president of the Center for Social Inclusion.

0 Comments