Raleigh, North Carolina

From a distance, North Carolina’s Moral Monday Movement reads like a spontaneous reaction to Republican Governor Pat McCrory and the Republican supermajorities that control the General Assembly.

Before adjourning this past September, North Carolina’s Tea Party-dominated General Assembly eliminated 5,200 teaching positions and 4,580 teacher assistants, they cut pre-K classes for 30,000 preschoolers and diverted $10 million to a school voucher program. They terminated unemployment benefits for 170,000 out-of-work North Carolinians and denied Medicaid to 500,000 qualified recipients. They abolished the earned-income tax credit for 907,000 working-class residents of the state—and they reduced taxes for the top 5 percent. Then to insulate themselves from voters who might respond at the polls, North Carolina’s Republican legislators passed the most restrictive ballot access law in the nation—specifically targeting minority voters.

William Barber: “How do you claim to be following Jesus if you don’t want to see people get health care? Health care is one of the things Jesus majored in.”

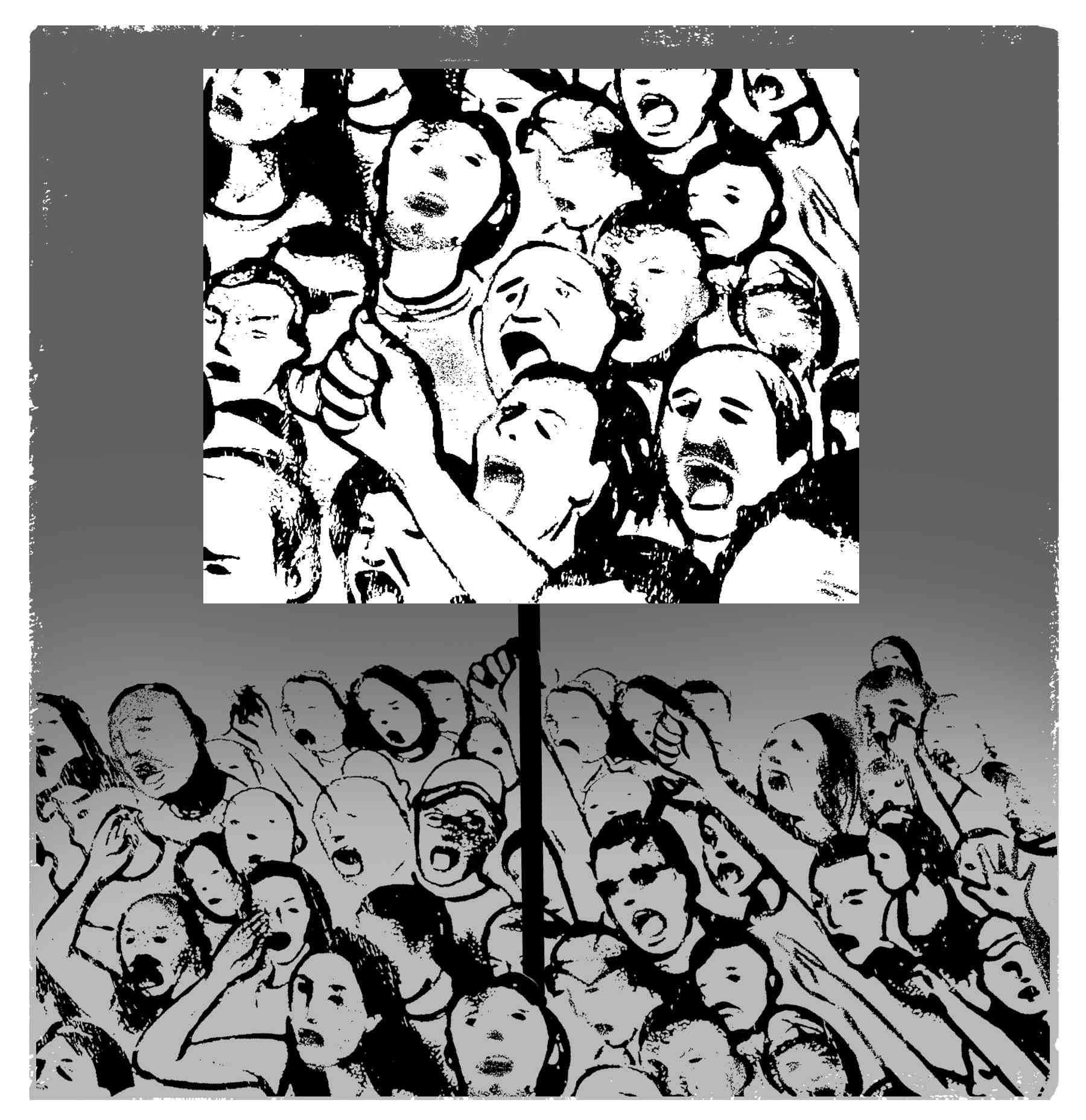

In response, a charismatic African-American preacher rose up and led tens of thousands of aggrieved citizens to mass rallies at the Capitol in Raleigh, where 350 protestors were arrested for committing acts of civil disobedience.

That’s a great story. It’s what many news outlets reported. But it’s not what happened.

“This movement began in 2005,” Al McSurely told me, “when Rev. Barber decided he was going to run for president of the NAACP.” McSurely doesn’t get into his personal history, but he joined the Congress of Racial Equality in Virginia in 1962. Then in 1967, he and his wife were charged with sedition in Kentucky in a political prosecution for their attempt to bring working-class whites into the civil rights movement. After the couple was exonerated and the state sedition statute ruled unconstitutional, Arkansas Senator John McClellan went after them, subpoenaing movement-related files that state investigators had illegally taken from the McSurelys’ home.

Alan and Margaret McSurely sued McClellan and the staff of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations and won $1.6 million. Al McSurely used some of these funds to go to law school in North Carolina and has been litigating civil rights cases there ever since. In 1986, he was one of the co-founders of the Chapel Hill branch of the NAACP.

McSurely was explaining the background of the Moral Monday Movement as we drove from Chapel Hill to Goldsboro to attend Sunday services at the Greenleaf Christian Church, the 120-year-old congregation where Rev. William J. Barber II serves as pastor.

“Rev. Barber said he wanted to move from banquets to battles,” McSurely said. “He wanted the NAACP to focus to the state Legislature.” Barber envisioned an aggressive political agenda for an organization that spent too much time on social activities and was too invested in a single NCAAP Lobby Day at the Legislature.

When Barber won the election, he brought McSurely on to his executive leadership committee. McSurely remains one of two white advisors working closely with Barber. He also directs an NAACP program that investigates unfair convictions and sentences.

On the road to Goldsboro—a city of 37,000 that is 50 miles southeast of Raleigh and 54 percent African American—McSurely reminded me of something often ignored by reporters: the issue of race remains central to any progressive political movement in the South. Barber gets that, McSurely said. He also understands the importance of building broad coalitions with white progressives.

William Barber is an ordained minister with an undergraduate degree in political science and a Ph.D. from Drew University in New Jersey, where he studied pastoral care and public policy. In North Carolina, he had worked for Democratic Governor Jim Hunt, McSurely said, and had come to recognize the limitations of the traditional arrangement by which African Americans and white liberals cut deals with the Democratic Party on the four or five bills the leadership would allow each legislative session.

Barber believed that the NAACP, with established branches across the state, could lead a broad progressive coalition that might change North Carolina’s political culture—if the NAACP itself would change.

He told NAACP members at an Emancipation Proclamation Banquet in early 2006 that he was taking the organization in a different direction. “We’re not a social club,” Barber said. “If you came here to smile at everybody, you’re in the wrong organization.”

He reminded them that they were celebrating the Emancipation Proclamation in Halifax County, once the home of iconic civil rights leader Ella Baker:

“She led the founding of the SNCC movement when young folks decided that the old folks were moving too slow.”

Social Justice Gospel

The Greenleaf Christian Church is a nondescript, low, brick-veneer structure with a small white steeple that looks like an afterthought attached to a composition roof. The interior, though, is warm and elegant: natural wood arches, a natural wood ceiling, rows of alabaster pews. (The church also has incorporated a community development center that buys and sells affordable homes in the Greenleaf community and operates its own retirement home and food-service job training center.)

Barber is a large imposing man with mobility problems that require him to use a cane. In sacerdotal garments, he is even more imposing.

He had been traveling. Early in the previous week he was in Mississippi, speaking to the NAACP about Moral Monday. On Friday morning, he addressed the Union Theological Seminary in upper Manhattan and that evening in New Jersey, he spoke at Princeton.

I had been told that this Sunday’s sermon would be delivered by a visiting preacher.

Yet standing in center of the aisle rather than on the altar, and speaking into a hand-held microphone, Barber was leading his congregation through the liturgy.

The healthcare.gov site was still in the repair shop and under attack from some conservative politicians and preachers. In a homily informed by the Social Justice Gospel, Barber got his licks in.

“I say to my brothers and sisters in faith, I call them brothers and sisters though I deeply disagree with them …” Barber said. “If you don’t have your health, you can’t make it. They are pro-life inside the womb and anti-health care outside the womb.”

He defined health care as a fundamental moral issue and challenged conservative Christian leaders who “make abortion, prayer in school, and where you stand on homosexuality the only moral issues.”

He questioned politicians who “put their hand on the Bible and swear to uphold the Constitution.”

“Do they know what’s in that Bible? If Jesus did anything to challenge the domination of Rome—where people were left to die if they weren’t in the 1 percent—the one thing Jesus did everywhere he went was to set up free health clinics.

“He would go to a pool where people were sick and he would heal them.

“He would find someone who had been lame for all of his life … and he would heal him.

“How do you claim to be following Jesus if you don’t want to see people get health care? Health care is one of the things Jesus majored in,” he said.

To conclude, Barber turned to the Old Testament and quoted from the 103rd Psalm:

Praise the Lord, my soul

and forget not all his benefits

who forgives your sins

and heals all your diseases.

“Heals all your diseases,” he repeated.

Before turning the pulpit over to a seminarian who would deliver the sermon, Barber led the congregation in “Come by Here”—better known as

“Kumbaya,” the English corruption of the original Gullah, the slave creole language spoken on the southeastern Atlantic coast.

“Slaves sang that song,” he said, “asking God to ‘come by here.’”

“God comes through the back door of history because that’s where his people are,” Barber said. “Not a temple, a stable.”

Not a moment, a movement

Not a moment, a movement

After the service, I accompanied Barber to a potluck lunch in the home of a member of the Greenleaf congregation in a middle-class rural subdivision a few miles from the church.

Barber agreed when I suggested that the Moral Monday Movement is perceived to be a reaction to the hard-right Republican agenda in Raleigh.

“That’s the biggest misnomer,” he said.

“People don’t understand this. They don’t understand how we did this. How long we have worked to create a legal strategy, a legislative strategy, a social media strategy. The number of plannings and meetings. What we did to get people to trust this movement. What gives the movement integrity, so we can’t be criticized by people who say you’re only doing this because of the Republicans.”

“We started this when the Democrats were in power,” Barber said. “We put out the word. The state had not complied with the Leandro decision [a 1994 public-education equity lawsuit]. We still had not given public employees collective bargaining rights. We didn’t have a racial justice act.”

“State legislatures have enormous power,” Barber said. “They control the budget. They control redistricting. They control voting rights. So we said, let’s focus on the Legislature.”

“Hence, HK on J”—Historic Thousands (i.e., K) on Jones Street, where the Capitol is located. “Al came up with that idea,” Barber said.

The NAACP became the organizing nexus for a coalition of progressive organizations ranging from organized labor to environmental advocacy groups.

At the first HK on J assembly in February 2007, 5,000 activists from across the state descended on Raleigh and produced a 14-point agenda with 84 specific action points.

“Education was key,” Barber said. “And economic justice, voting rights—important issues.”

At the time, Democrat Jim Hunt was governor and both chambers of the state’s General Assembly were controlled by Democrats.

While Democrats were in power, the movement pushed the General Assembly to pass legislation that included same-day registration and early voting, and a racial justice law that protected against bias in capital cases.

“It’s not like the Democrats handed that to us,” Barber said. “We had to fight the Democrats and the Republicans.”

When Republicans elected a governor in 2010, and supermajorities in both houses of the Legislature in 2012, Tea Party influence made a backlash inevitable—though few anticipated the extremism of the 2013 session.

“If you take the Tea Party’s agenda and go right down it, and go right down our agenda, you will see that they are attacking everything that we won and everything that we did,” Barber said.

Because Obama didn’t win the popular vote in North Carolina in 2008 until the early-registration, same-day-vote tally was added in, election reforms pushed through the legislature by the HK on J coalition were an obvious target.

North Carolina’s new voter ID law, the most extreme and restrictive ballot access legislation in the nation, is being challenged in court by the NAACP, the League of Women Voters, and the Justice Department.

“Their goal has been to undermine and roll back those victories and to undermine and keep this sort of fusion political momentum from going on,” Barber said.

Moral Monday would become the movement’s response to a Legislature bent on dismantling the state’s social-welfare safety net.

A Third Reconstruction

Spend any time in the company of Barber, or Tim Tyson, the Duke University historian who is part of Barber’s inner circle, and you quickly get acquainted with the term “fusion politics.”

Fusion politics brought together newly enfranchised blacks and progressive whites who drafted a constitution in North Carolina in 1868 during the First Reconstruction. Two years later, the General Assembly passed voting rights laws, criminal justice laws, labor laws, and created the first public school system in the United States.

“That was progressive legislation passed by blacks and whites working together,” Barber said.

Until a backlash that, according to Barber’s reading of history, anticipated what is happening in North Carolina today.

In 1872, the Ku Klux Klan was created—“as a political organization,” Barber said—and North Carolina’s planter class began to claw back the gains made by the fusion politics coalition.

In 1898, whites rioted in Wilmington, killing a still-unknown number of blacks. The Old South insurgents seized control of the General Assembly and re-disenfranchised black citizens who had been working in concert with progressive whites.

“By 1910, black voting power was virtually nothing,” Barber said.

Barber and Tyson describe the history of the South as a Manichean struggle between progressives and retrogressives.

“State legislatures have enormous power. They control the budget. They control redistricting. They control voting rights. So we said, let’s focus on the Legislature.”

“When they saw what fusion politics was doing, they went after taxes, education, and most importantly voting rights,” Barber said.

“It’s an ongoing struggle between the spirit of slavery and the spirit of citizenship that’s been going on in North Carolina for a century and a half or more,” Tyson said at a Moral Monday meeting.

The Second Reconstruction began at about the time the Supreme Court handed down the Brown decision in 1954 and also involved fusion politics.

“Remember, it was blacks, whites, Jews and Gentiles,” Barber said.

The Second Reconstruction ended with the assassination of civil rights leaders and a programmatic assault on the same progressive laws that had been dismantled in the post-Reconstruction South: public education, fair criminal justice laws, equitable taxation and voting rights.

The election of Barack Obama, more specifically the demographic mix of voters who elected and reelected him, represents “the possibility” of a Third Reconstruction, Barber proposed. The extreme measures the extreme right is writing into law across the South, in particular the assault on voting rights, are aimed at suffocating that possibility.

“We are being attacked because of our success,” Barber said.

“They know that in North Carolina about 23 percent of the electorate is African American. So you get 26 to 27 percent of whites to vote their future and not their fear, add a percentage of Latinos, and you have a whole new day. Their Southern Strategy no longer works for them.”

War clothes

The following day, there were five people in the sanctuary of the Gethsemane Missionary Baptist Church in Salisbury when I arrived, half an hour before the November 18 Moral Monday rally was scheduled to begin.

Barber was speaking to SiriusXM talk show host Mark Thompson and appeared unconcerned that the room was empty.

Half an hour later, the 500-seat sanctuary was filled and an overflow room was opened.

Gethsemane is located in Salisbury’s African-American community, directly across the street from Livingstone College (which was founded by J.W. Hood, a black state superintendent of schools during North Carolina’s First Reconstruction).

Salisbury, 100 miles west of Raleigh, is 38 percent black, and the crowd that came together in this African-American church was mostly, perhaps 85 percent, black.

The other 15 percent represented interests as broad as the movement Barber is building. Working my way through the sanctuary, I spoke to a UAW Local president and half a dozen of his union brothers, all white; two white teachers who are members of the North Carolina Association of Educators; a Mexican-born college student advocating for immigration reform; a member of the North Carolina Nurses Association who wanted to make a statement about the governor’s decision on Medicaid; and a lesbian pastor of a Baptist Church who two years earlier was arrested for protesting an anti-gay measure enacted by a county school board.

(The movement can also draw a white crowd; five hundred white people, for example, turned out for an August 19 Moral Monday rally sponsored by the NAACP in Burnsville, a town of 1,600 in Yancey County, where blacks represent 1 percent of the population.)

The event in Salisbury lasted for three hours and included three panels and a selective reading of the Moral Monday “Legislative Report Card.” Yet more than two-thirds of the crowd stayed until the end, waiting to hear Barber speak.

Barber walked to the pulpit and began quietly but forcefully with Isaiah 10:

“Woe unto those who legislate evil.”

Then, after a 17-minute breathless and breathtaking jeremiad that built in emotional and rhetorical intensity while defining the evil legislated in Raleigh, he concluded with the question asked in the 94th Psalm:

“Who are the people who will stand up against iniquity?”

And he answered:

“I’ve got my war clothes on!

“I’ve got my war clothes on!

“I’ve got my war clothes on!”

It was as powerful a speech as I have personally witnessed. William Barber and more than 10,000 Moral Monday activists will again converge on the Capitol on February 8. The Governor and his Tea Party allies can expect the Reverend to have his war clothes on.

Lou Dubose is the editor of The Washington Spectator.

0 Comments