With the government set to reopen and the threat of default evaded for now, fears are emerging that the resulting fiscal austerity and financial uncertainty may have seriously weakened the recovery (by as much as $24 billion). But it’s worth looking at exactly what’s being jeopardized.

Independent of the GOP’s games of chicken, the recovery that started in 2009 is nothing to write home about. In fact, this recovery is one of the most cartooonishly lopsided episodes of economic growth on record.

| Analysts estimate that the shutdown of the federal government cost as much as $24 billion. But to working people, it was just another chapter of the Great Recession. Since 2008, workers have seen their bargaining power, and their paychecks, plummet. |

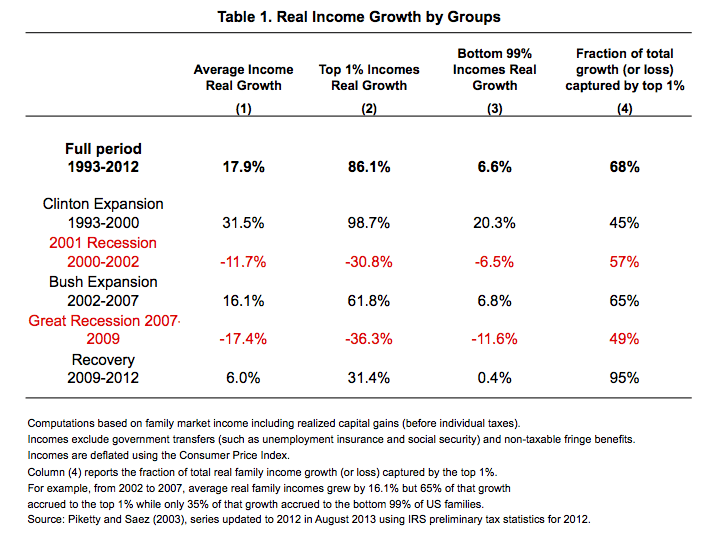

Among the most important scholars of U.S. income inequality is Emmanuel Saez, professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley. His influential and recently-updated paper, “Striking It Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States,” compares the income gains of the richest 1 percent of households to those of the remaining 99 percent, finding in part that: “Top 1% incomes grew by 31.4% while bottom 99% incomes grew only by 0.4% from 2009 to 2012. Hence, in the first three years of the recovery … top 1% incomes are close to full recovery while bottom 99% incomes have hardly started to recover.”

To have accumulated 95 percent of the growth in U.S. income through the recovery is absolutely bananas, and is hard to explain on the traditional theoretical grounds of marginal productivity.

More elite sources, like this year’s Forbes 400 list of the richest Americans, confirm this picture of the recession and recovery. The magazine’s summary:

“Five years after the financial crisis sent fortunes spiraling, the wealthiest Americans have gained back all they lost and then some. The Forbes 400 are worth a record $2.02 trillion, double the sum of a decade ago—and the equivalent of the economic output of Russia. This year a billion-dollar fortune wasn’t enough to make the cut. Some 61 billionaires didn’t qualify. The minimum? A personal fortune of $1.3 billion.”

Meanwhile, the current edition of The State of Working America, compiled by the staff of the Economic Policy Institute, reports that the average household in the middle-fifth of the country by wealth lost 45 percent of its wealth in the recession and has essentially flatlined since.

The affluent themselves seem to be aware of the basic picture already. Consider a recent Wall Street Journal feature, “Suites Get Even Sweeter,” about the over-the-top accommodations available for “people who don’t pay their own bills … They have people who pay their bills for them.” The recovery has seen strong growth of these massive “super-luxurious” suites, even as regular Americans struggle to keep the lights on. Amenities include in-suite bars and hair salons, floor-to-ceiling waterfalls, and the Abu Dhabi Ritz Carlton’s Royal Suite, with “a room for bodyguards next door.” An industry analyst describes the limited market for these spaces in the light of the weak upturn: “the recovery has been very uneven. You’ve got the haves and the have-mores.”

The dynamic behind these developments can be found in one of the many near-forgotten tracts by the father of modern economics, Adam Smith, who wrote in The Wealth of Nations that:

“A landlord, a farmer, a master manufacturer, or merchant, through they did not employ a single workman, could generally live a year or two upon the stocks which they have acquired. Many workmen could not subsist a week, few could subsist a month, and scarce any a year without employment. In the long-run, the workman may be as necessary to his master as his master is to him, but the necessity is not so immediate. We rarely hear, it has been said, of the combination of masters, though frequently of workmen. But whoever imagines, upon this account, that masters rarely combine, is as ignorant of the world as of the subject. Masters are always and everywhere in a sort of tacit, but constant and uniform combination, not to raise the wages of labor above their actual rate … Masters too sometimes enter into particular combinations to sink the wages of labour even below this rate.”

In other words, incomes for the 99 percent are not determined by the marginal productivity of the workforce but the bargaining power of working people, who have regular expenses for rent and health care and utility bills, against a thin upper elite of households that own and largely run the business world.

The Great Recession followed a financial crisis and a giant build-up of household debt, factors that tend to worsen downturns. Recessions further weaken the bargaining position of working people, which combined with the huge decline of the U.S. labor movement has left workers with little organizational bargaining power of their own, making them more vulnerable. That’s why the 99 percent has to share a pitiful 5 percent of the recovery’s total income growth, a heinous disgrace and a cruel mockery of the hard work of the American majority.

In the shadow of the shutdown, the have-mores have more reason to be nervous.

Rob Larson is Instructor of Economics at Tacoma Community College in Washington state. He is the author of Bleakonomics: A Heartwarming Introduction to Financial Catastrophe, the Jobs Crisis and Environmental Destruction.

0 Comments