From Ava Duvernay’s award-winning film to President Barack Obama’s speech at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, to the thousands we crossed the bridge with and the millions that joined by television, America has remembered Selma, Alabama, this year. We have honored grassroots leaders who organized for years, acknowledged the sacrifices of civil-rights workers, and celebrated the great achievement of the Voting Rights Act. At the same time, we have recalled the hatred and fear of white supremacy in 1960s Alabama. But we may not have looked closely enough at this ugly history. Even as we celebrate one of America’s great strides toward freedom, the ugliest ghosts of our past haunt us in today’s “religious freedom” laws.

Many have pointed out the problem of laws purporting to protect the First Amendment right to religious freedom by creating an opportunity to violate another’s 14th Amendment right to equal protection under the law. But little attention has been paid to the struggle out of which the 14th Amendment was born—a struggle that continued to play out in Selma 50 years ago and is very much alive in America’s state houses today. We cannot understand the new “religious freedom” law in Indiana and others like it apart from the highly sexualized backlash against America’s first two Reconstructions.

The 14th Amendment was part of America’s first Reconstruction. It guaranteed for the first time that people formerly codified as three-fifths of a person would enjoy equal protection under the law. The very notion of equal protection for black Americans was so offensive that it inspired an immediate backlash.

The pattern is clear: whenever established power brokers have felt threatened in America’s history, they have responded by stirring up sexual fears.

Two features of resistance to America’s first Reconstruction are essential to note. First, it was deeply religious. White preachers led the charge, calling themselves “Redeemers” and framing equal justice for black Americans as a moral danger. At the same time, the threat was explicitly sexualized. Black men were portrayed in respectable newspapers as “ravishing beasts” eager to rape white women. In North Carolina, white vigilantes were armed and encouraged to defend their women, leading to the “Wilmington Race Riot” of 1898. Violent demonstrations of white men’s sexual fear led to lynchings throughout the South and Midwest in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Ida B. Wells, the courageous African-American journalist from Memphis, did dangerous investigative work to show that the great majority of these lynchings were not about sex but political power.

When the Civil Rights Movement—a Second Reconstruction—was finally able to draw national attention to vicious patterns of Jim Crow in the 1960s, the challenge to white power was again conflated with sexual fear. As Danielle L. McGuire chronicled in At the Dark End of the Street, civil-rights workers were consistently accused of wanting interracial sex and/or having homosexual tendencies. We remember Dr. King’s “How Long, Not Long” speech from the Alabama Capitol at the end of the Selma-to-Montgomery March. But we often forget that the members of the Alabama Legislature responded with Act 159, citing evidence of “much fornication” among marchers and claiming that “young women are returning to their respective states apparently as unwed expectant mothers.” When Selma’s Sheriff Jim Clark published his popular memoir, he titled it The Jim Clark Story: I Saw Selma Raped.

The pattern is clear: whenever established power brokers have felt threatened in America’s history, they have responded by stirring up sexual fears. The widespread acceptance of interracial relationships makes “mongrelization” a moot point in 21st-century America. But one can see public expressions of concern about the “gay lifestyle” are not about religious freedom. They are about dividing an increasingly diverse electorate that has twice elected a black president. Fear of gay rights is a most effective strategy for extremists determined to take over America’s state houses.

As Southern preachers engaged in moral-fusion organizing, we say to our fellow ministers: “religious freedom” laws are an immoral ploy to stir up old fears. As people of faith, we must oppose them. But in light of this ugly history, we also say to our progressive sisters and brothers: it’s not enough to simply stand with the LGBTQ community.

We who are concerned about LGBTQ sisters and brothers must see the attack against them is also an attack on voting rights. While it is heartening to see business leaders and even the NCAA challenge Indiana’s law, we need the same forces to stand together against ALEC-backed voter-ID laws, voter-suppression bills and redistricting plans aimed at restricting voting rights.

In North Carolina, the proposed “religious freedom” bill goes so far as to say government employees may choose not to carry out their duties because of a religious objection. While conservatives’ concern today may be a religious objection to issuing a marriage license to gay couples, we remember well the religious reasons our neighbors in the South gave for segregation, the subjugation of women, and race-based slavery. Freedom of religion, a bedrock of American democracy, cannot mean a license to condemn others.

Fifty years ago, thousands marched in Selma as part of a faith-rooted, moral campaign to secure an expansion of voting rights. Extremists who couldn’t deny their cause sought to distract and divide the country by using moral and religious language to stir up old sexual fears. The mystery money and secretive organizing behind today’s “religious freedom” bills seek to do the same.

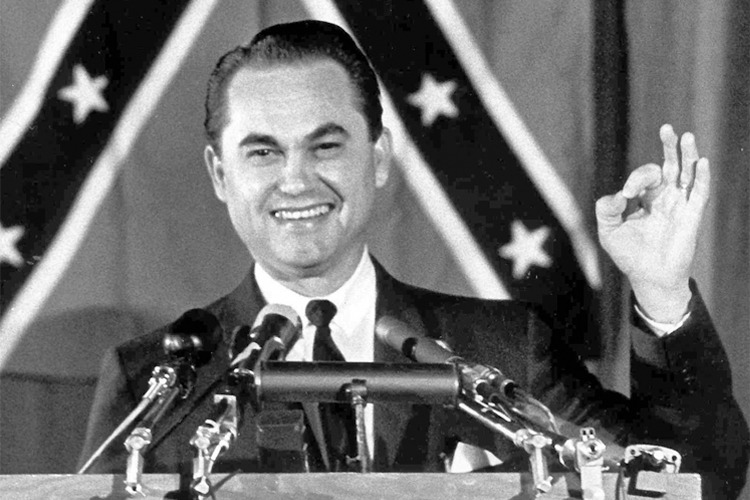

We must make clear, as Dr. King did, that religion serves the common good when it cries out against injustice, not when it dictates personal morality. Extremists in our state houses are echoing George Wallace and Jim Clark when they pretend to talk about morality in order to hold on to power. We would do well to pay attention to the moral witness of those who most now agree were on the right side of history.

Rev. William J. Barber II is Pastor of Greenleaf Christian Church, Architect of the Forward Together Moral Monday Movement, and North Carolina NAACP president. Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove is director of the School for Conversion.

0 Comments