Here’s how Donald Trump’s new immigration policy looks at ground level.

On the Monday afternoon before Valentine’s Day, Juan Manuel García was taking the office mail to the post office two blocks south of the Capitol in Austin, Texas, when he saw an unmarked black Dodge crew-cab pickup make a quick U-turn. An “anglo” man got out of the truck, grabbed García by his arm, and asked: “What’s your name?”

García told me he couldn’t recall if the man identified himself as a federal agent. García has a reasonable grasp of his legal rights. “I know I don’t have to say anything,” he said. “So I didn’t answer. Then four or five men got out of the truck and another guy grabbed me and they pulled my arms behind my back.”

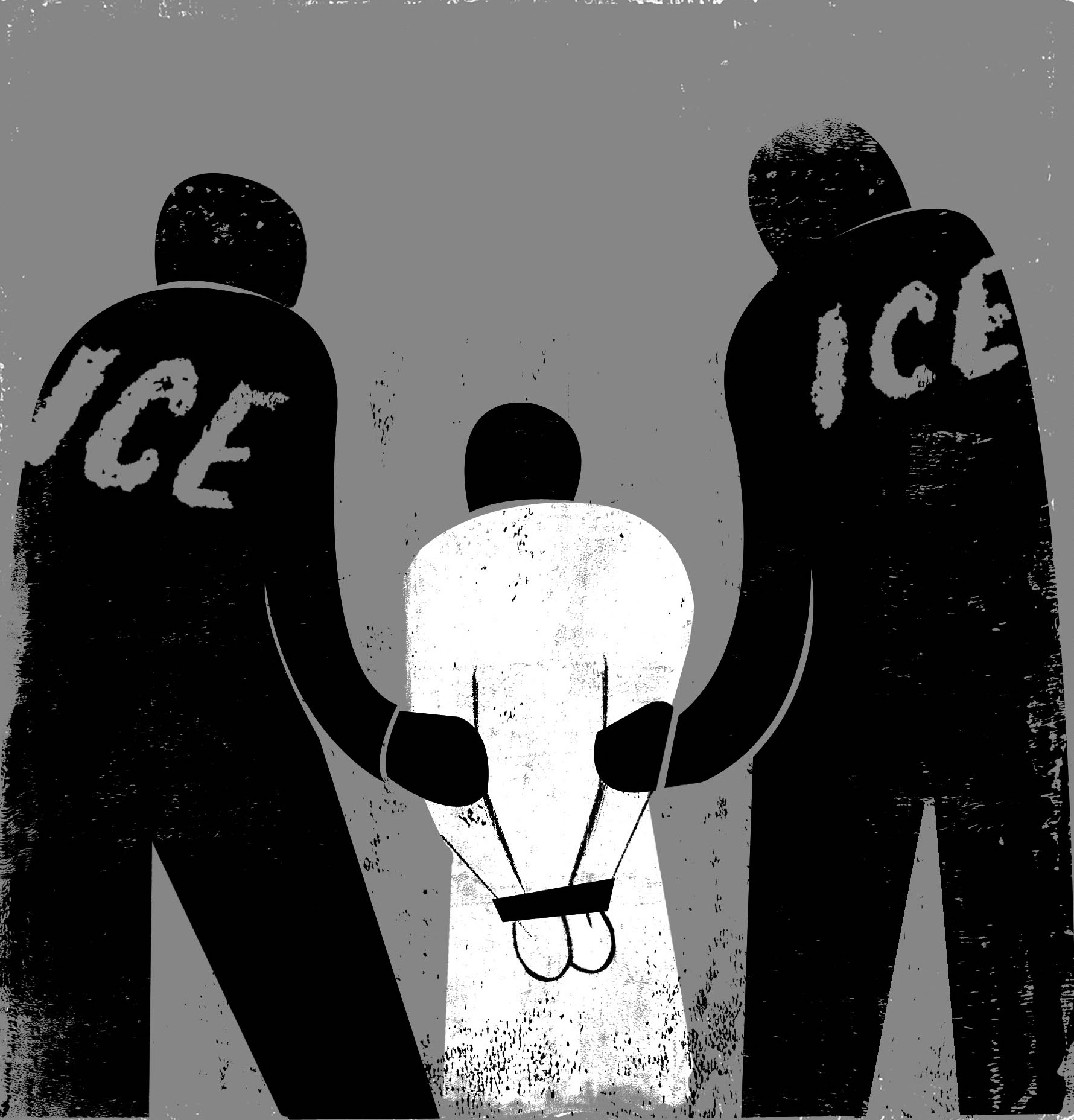

The men who got out of the truck were wearing ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency) vests, García explained. “The Hispanic guy started asking me questions in Spanish. He thought I didn’t understand English,” García said.

The Spanish-speaking agent said there is a Texas law that requires anyone who is asked a question by a police officer to respond. García told the agents his name as one of the men reached into Garciá’s pocket and took out his wallet. The officer found an expired Texas driver’s license, returned the wallet, and told García he was free to go. As he walked away, one of the agents followed him and showed him a cell-phone photo of a “Hispanic looking,” man, explaining that García was stopped because of his resemblance to a suspect they were looking for.

“The man in the photo looked nothing like me,” he said. Except that he was Hispanic.

García, like 60 percent of undocumented residents of the United States, had been in the country for more than 10 years. He has worked for the same employer for 20 years. He and his wife are undocumented Mexicans. Their 17-year-old son attends a public high school and is a temporary legal resident under Barack Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival status (DACA) executive order. Their three younger children, the youngest at 11 months, are U.S. citizens by birth.

‘The man in the photo looked nothing like me.’

Malcolm Greenstein, a criminal defense lawyer with a practice in Austin, said Texas law did not require García to respond to police in the circumstance described. He also said the agents violated constitutional protections against unwarranted search and seizure, in particular in taking García’s wallet. “And, it looks like he was profiled,” Greenstein said. (Note: the subject’s name was changed to protect his identity.)

For a full week in February, what happened to García played out across half a dozen cities across the country as ICE previewed new enforcement tactics detailed in two February 17 implementation memos signed by Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly.

In a press release, Kelly described “targeted enforcement operations across the country,” in Austin, Los Angeles, Chicago, San Antonio, and New York City, and reported that 680 undocumented immigrants were taken into custody. Kelly said the coordinated raids targeted “individuals who pose a threat to public safety, border security, or the integrity of our nation’s immigration system.”

New Rules

Statements from the Trump Department of Homeland Security require careful parsing. García did not “pose a threat to public safety.” But under Trump DHS rules his presence in the country was a threat to the “integrity of our nation’s immigration system.” While Barack Obama was commander in chief of the nation’s immigration cops, García would not have been defined as “deportable.” Under guidelines detailed in the DHS memos, he was one wrong answer from lockup in an ICE detention facility (or a quick trip to Mexico, were he to accept voluntary deportation as many ICE detainees do to avoid prolonged incarceration). The two memos implementing an executive order Trump signed on January 25 “are a blueprint for mass deportation,” said David Leopold, the past president of the American Immigration Lawyers Association. They define a radical departure from the immigration enforcement policy of the two previous administrations and reflect the anti-immigrant sentiment that Trump crudely articulated the day he announced his presidential campaign, departing from his written text for an impromptu riff on Mexicans—“They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.”

Trump’s take on immigrants is not exactly grounded in reality. Studies consistently find that undocumented immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than native-born U.S. citizens, but Trump’s “bad hombre” characterization of criminal aliens now becomes canonical at the DHS. One of Kelly’s memos describes law enforcement agencies overwhelmed by criminal aliens—as did Trump when he described “the military operation” on the Mexican border.”

“[F]or the first time, we’re getting gang members out, we’re getting drug lords out, we’re getting really bad dudes out of the country. . .” Trump said after the February raids.

Kelly’s directives require the hiring of 10,000 new ICE agents, 5,000 border patrol officers, and 500 additional marine and air officers, and expanding a program that enlists state and local police to serve as an extended immigration police force.

While previous administrations released many detainees on bond until hearings before immigration judges were scheduled, Trump policies require prolonged detention. Most will be held in private prisons (some yet to be constructed), at a cost of $9 million over the next 10 years.

Barack Obama, whom a member of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus once derisively referred to as “our deporter in chief,” had directed ICE agents to focus on “criminal aliens who represent a threat to public safety.”

Trump policy casts a much broader net and will inevitably snare “non-criminal” aliens along with the criminals.

García was wise to refuse to answer the agent’s questions. And lucky.

Three days earlier, and six miles from where he was detained, ICE agents stopped a Mexican couple driving to their cleaning jobs in the pre-dawn darkness. Asked for identification the couple produced Mexican identification cards. Probable cause for the stop was as tenuous as it was when agents grabbed García. The previous resident of the house the couple rented had been engaged in questionable activities. The husband consented to voluntary deportation and the following afternoon was in Torreón, Mexico, separated from his wife and children. His crime: driving without a valid license.

Austin’s ABC affiliate reported that 23 of the 51 people detained in the February raids had criminal records, the others were classified as “non-criminals.” Nationally 25 percent of undocumented residents detained were “non-criminals,” according to the DHS.

“This is the beginning of a reign of terror and fear in the nation’s immigrant community,” Leopold said in a Facebook video.

Immigrants have good reason to be afraid. A statement a DHS official made to The Washington Post in mid-February redefined a “criminal alien” as “anyone who had entered the United States illegally or overstayed or violated the terms of a visa.”

That is, all 11 million undocumented residents of the United States.

0 Comments