Is it still acceptable to be fixated on Donald Trump’s iron grip on millions of Americans? While most people seem to have moved on, I’d argue that getting to a true understanding of his appeal is still of vital interest. Indeed, people’s lives may depend on it. Election officials continue to receive death threats for challenging his election lies. A large-scale violent insurrection appears plausible if he loses again in 2024.

We should not buy into simplistic explanations like “They’re all racists” or “He starred in a hit reality TV show.” Something much more profound is at work. One half of the country perceives Trump to be an incompetent and psychologically troubled man of dubious achievements. The other half sees him as the only human being on the planet who could ever solve their problems. Many of these appear ready to kill and die for him.

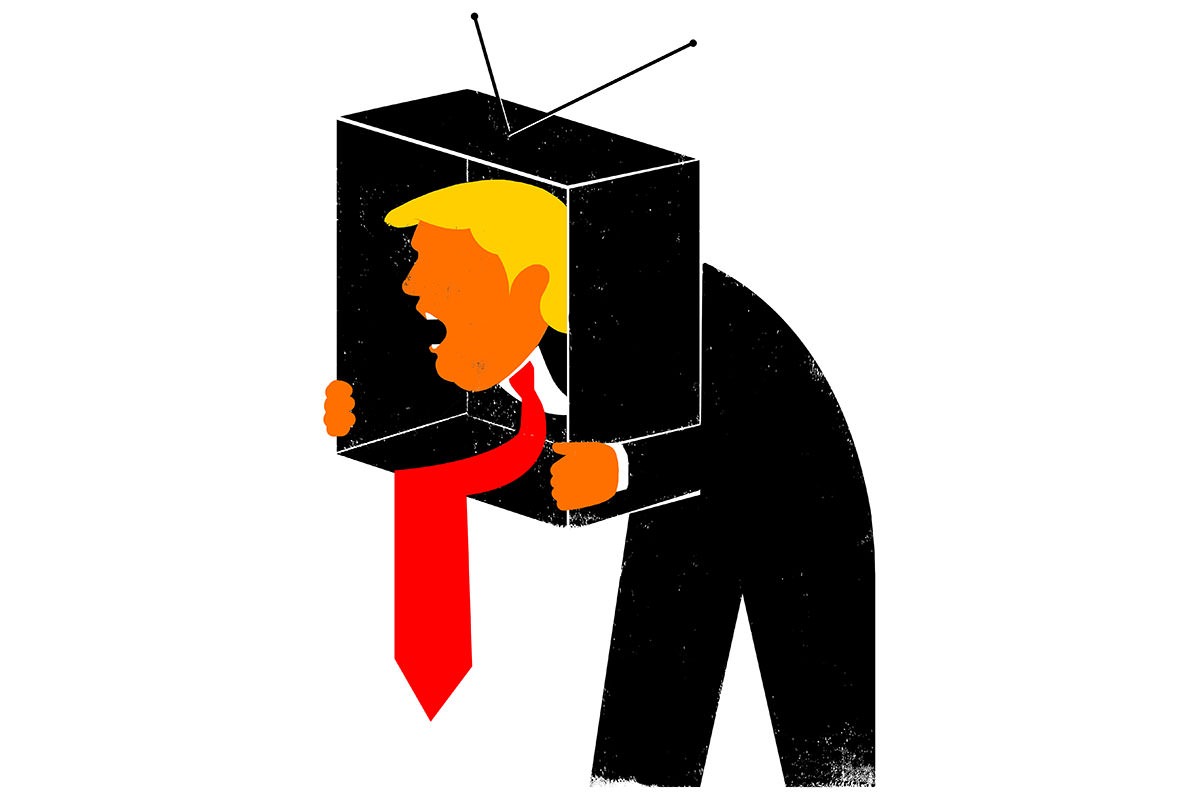

To understand this astonishing perceptual divide, we need to revisit what we think we know about television as a medium. When we talk about reality TV, we owe it to ourselves to investigate our conceptions of “reality” and “TV,” both of which have evolved significantly in the last decade or so. Trump’s impact on television audiences is related to profound changes in the medium itself. These changes have occurred slowly enough to escape serious notice by people who want to understand how a talented performer like Trump can gain such influence over people. While television is not the only factor that explains Trump’s grip on his supporters, it is arguably the most important, especially when assessing his early popularity with voters.

The roots of today’s competing realities lie in the evolution of reality television itself and its effects on viewers’ brains. This is a story that starts in the early 1960s; a story I participated in as my career progressed from producing made-for-TV movies to serving as Social Software Evangelist at IBM.

In the summer of 1960, the French filmmaker Jean Rouch, who had spent the previous decade making documentaries about African tribes, took his portable Éclair Cameflex 16-millimeter movie camera out onto the streets of Paris to interview real people in their daily lives. The resulting film, Chronique d’un été (Chronicle of a Summer) was both a technical and artistic breakthrough. The equipment was revolutionary. No sound camera had ever been so portable. Also revolutionary was the idea of making a movie about regular people just casually talking about the issues of the day, such as the French colonial war in Algeria. It was one of the first cinema verité films.

The whole purpose of cinema verité was to be real. The filmmaker would always have a point of view, and there is no such thing as true objectivity, but the goal was to record reality as it was, with as little interference as possible.

This “cinema of truth” or “observational cinema” existed mostly in the realms of public television and art house documentaries, with a few breakouts like Michael Wadleigh’s Woodstock and PBS’s An American Family achieving popular success. At the same time, the verité technique was establishing itself in the mind of the audience as a window onto reality. The effect emerged mostly from the use of the verité style in television news, with portable cameras bringing us “film at 11.” This perception, that informal filming of real people reflected reality, would have major implications for television as a medium—and also, as we would later discover, politics.

My involvement with verité came 25 years after Jean Rouch hit the streets of Paris with his Éclair camera. After studying with some of cinema verité’s most celebrated practitioners, I took a job in primetime television. My mentor was Edgar Scherick, the fiery-tempered former president of ABC. In the 1950s, Edgar had created The Wide World of Sports. He went on to produce dozens of television movies and feature films like The Stepford Wives and The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3. Later, he’d brought an unknown 19-year-old New York casting director named Scott Rudin to Hollywood.

By 1988, when I joined his production company as a cigar-fetching assistant, Scherick’s main gig was dramatizing true stories as made-for-TV movies. This was a format that, in retrospect, was a bridge between traditional, completely fictitious television and what we now consider reality TV.

Though now extinct, the true crime movie of the week was a reliable source of high ratings in the 1980s and early ’90s. Every network made it a staple of their programming schedules. No one could adequately explain why the audience was so hungry for true crime docudramas. One theory, which I am skeptical of, was that people tended to feel guilty about watching TV, so they rationalized consuming endless gore and dramatizations of depraved behavior with the excuse that they were informing themselves about the news of the world.

I suspect audiences were actually getting trained to view docudramas as inherently true. The barrier between reality and fiction, what I would call the “fifth wall” of onscreen programming, was beginning to crumble. Most films and TV shows respect the “three walls” of the stage set, with the “fourth wall” functioning as an invisible barrier between the camera and the action. Sometimes, an actor will “break the fourth wall” and speak directly to the camera. This is common in reality TV, but more and more, as time went on, the fifth wall also began to deteriorate.

Probably the first serious erosion of the fifth wall came in 1989 as the cinema verité genre enjoyed its first major primetime hit with Cops, on the Fox Network. Scherick worked on a project with the producers of Cops. It was in this context that I learned Cops was betraying cinema verité’s most sacred rule of not interfering in the subject’s life.

This bothered me, though it’s hilarious in retrospect that I was upset that Cops was staging confrontations between real people to get tape of entertaining arguments. What did I expect? This was hardly the Cinémathèque Française. This was TV, produced for commercial entertainment and beholden to no rules about telling the truth.

The problem was that Cops looked like pure, unaltered real life. The audience got to ride along in cop cars and see the police at home with their families. The audience learned that an exciting TV show could be about real people, taped living their everyday lives. The show was trading on the belief that unposed, poorly lit and seemingly unscripted video reflected real life. It had the “film at 11” look, so it had to be true, right?

I don’t mean to imply that TV viewers are so ignorant that they can’t tell the difference between fiction and reality. Subsequent reality programming has been transparently fake, with ordinary people set in highly contrived and obviously scripted scenarios. It’s called scripted reality programming, an oxymoron that bothers no one. The audience today knows it is watching real people staging fake scenes. At the level of brain function, however, the distinction has been blurred.

This insight is critical if you want to understand Trump’s power over his audience, especially early in his rise. If you’ve ever felt dizzy watching a car chase scene, you’ll understand that our brains tend to process events on a screen as if they were really happening to us. This is a well-documented neurological phenomenon. Jean Rouch called it the “ciné trance” a state of mind where your brain is in the scene you’re watching. You really are there, walking with him on the streets of Paris in 1960.

The verité trend in reality television also eroded the boundaries of exploitation and voyeurism in the medium. Watching dramatizations of true crime stories whetted the audience’s appetite for voyeuristic glimpses through the curtains of their unfortunate neighbors. The reality TV movement served the main dish: a voyeuristic spectacle of sadism. Americans might have once felt guilty about enjoying a show like The Apprentice, which reveled in humiliating people, or American Idol, which glamorized the abuse of the weak. As the reality trend wore on, audiences were given permission to enjoy others’ misery as entertainment and protagonists like Trump were given a pass for being ruthless and denigrating. Trump is a true master of this art form.

Rouch’s ciné trance is a naïve notion compared with the immersion in manufactured reality that American TV audiences experience today. News channels are designed to entertain. They’re bracketed by hours of scripted reality on the programming schedule, and it’s all punctuated by commercials that feature unreal effects like talking batteries. The ciné trance has morphed into a permanent TV trance—a state of mental suspension in which the action on screen is perceived as reality, and therefore true, even if the conscious mind is aware that it’s fiction—made up and manipulative.

The experience of watching TV has also fused with reinforcing technology habits such as Twitter and Facebook. Audience members continuously trigger addictive centers in their minds with integrated loops of television programming and follow-on tweets and social media posts. YouTube and Instagram’s ubiquitous mobile phone videos compound the effect. We’re addicted to media stars we know are fake but neurochemically perceive to be real.

Trump was a force in this trend, as well as one of its main beneficiaries, as are Oprah, The Rock, and other fantasy presidential candidates who present fictional projections of themselves in the media. By 1990, Trump had become interested in being on television. Having gone bankrupt from the failure of his Atlantic City casinos, with creditors and law enforcement nipping at his heels, he needed a new way to make money. It was time for him to become rich by being famous, as he could no longer get famous from being rich.

Trump’s attorneys reached out to Scherick, then one of the highest-profile “go to” people in the industry, and struck a deal for one of Donald Trump’s first TV projects. It was to be called Trump Tower, a nighttime soap opera on NBC pitched as “Dynasty meets the Algonquin Round Table.”

We hired Clare Labine, co-creator of Ryan’s Hope, to write the pilot, which would take the form of a four-hour miniseries. The idea was to present a byzantine melodrama among sophisticated New Yorkers who lived in Trump Tower: major artists, prominent authors, tycoons . . . all sleeping with each other while hatching diabolical plots of sadistic revenge and schadenfreude for past betrayals.

In the background would be Donald Trump, playing a fictitious character named Donald Trump. He would be Donald Trump, the well-known real estate magnate, but with his lines written for him. He was envisioned as a sort of quiet Machiavellian character, moving the chess pieces of people’s lives around without their knowing it.

After the project began, Scherick got another call from Trump’s lawyers. There was an actress named Marla Maples who would need to have a role in the series. “The mistress,” Edgar had murmured… The lawyers hadn’t said it out loud, but their intent was clear.

The show never got on the air, but from the perspective of 2022, it’s an informative missing link in Trump’s biography. He later landed a hit with The Apprentice, which again featured him playing a fictional version of himself. This characterization of Donald Trump was of a powerful, decisive, and competent leader, a father figure who always knew the right thing to do—demonstrably the opposite of his true nature.

This is the Donald Trump his supporters admire. His characterization on The Apprentice differentiates him from other political figures who perform well on TV but simply cannot muster the audience buy-in that Trump easily commands. It’s entirely a false persona, but the audience was never fully clued in on how much of the show was fabricated versus how much of it was real. And given the TV trance that had taken effect, it apparently didn’t matter. People loved the show. They loved Trump and the tough, can-do character he played. Whatever their rational minds might have told them, their brain chemistry had them solidly believing he was the resolute, infallible master of their collective destiny. He was real, in their brains, even if they knew he was not. And he delivered the delicious helpings of sadistic voyeurism the audience so craved.

We know what happened next. Today, the country confronts a politician whose base thinks he can do no wrong. I suspect that they are to a large degree in the grip of the TV trance. Their deep brain functions are convinced that Donald Trump, the fictional TV character, is a real person with immense, unique powers, despite what observable reality might tell them.

As to what should happen now, I don’t have any clever ideas. I do think that if there is to be any effective movement against Trump, it should consider the brain connection he has with his television audiences. Screaming “you’re a racist” at his followers is not the answer. Instead, it might be more useful to engage and explore why they feel he’s real in their hearts while they know he’s not real in their heads. Such an approach would at least be moving along a path to the truth and to deconstructing the paradox of Trump’s verité.

Hugh Taylor is a technology analyst and author of the book Digital Downfall: Technology, Cyberattacks and the End of the American Republic. Prior to working in the tech field, Hugh was a script development executive in primetime television.

He studied filmmaking at Harvard University.

0 Comments