The signs of a U.S. infrastructure crisis are unmistakable—derailing trains, crumbling roadways, undrinkable tap water, and wastewater systems that endanger public health. Twenty-three U.S. bridges have collapsed since 2000.

The American Society of Civilian Engineers gave U.S. infrastructure a D+ grade in 2017, proclaiming $1.5 trillion’s worth of improvements was required over the next decade. They estimated that infrastructure deficiencies cost each U.S. household, on average, $3,400 annually.

But these costs do add up. Long, brutal commutes reduce worker productivity and wages. Congestion on roads and rails increase transportation costs for firms, which then raise prices for the goods we buy. Consumers pay for car repairs due to poor quality roads and additional health care costs due to poor quality water and sewage treatment. Large costs arise as lives are destroyed when bridges and roads collapse, and property is destroyed when dams and levees breach, causing massive flooding. Minneapolis’s Interstate Highway 35 bridge collapse in 2007 killed 13 people and injured 145.

Clearly, something must be done. The $1.5 trillion question is: What?

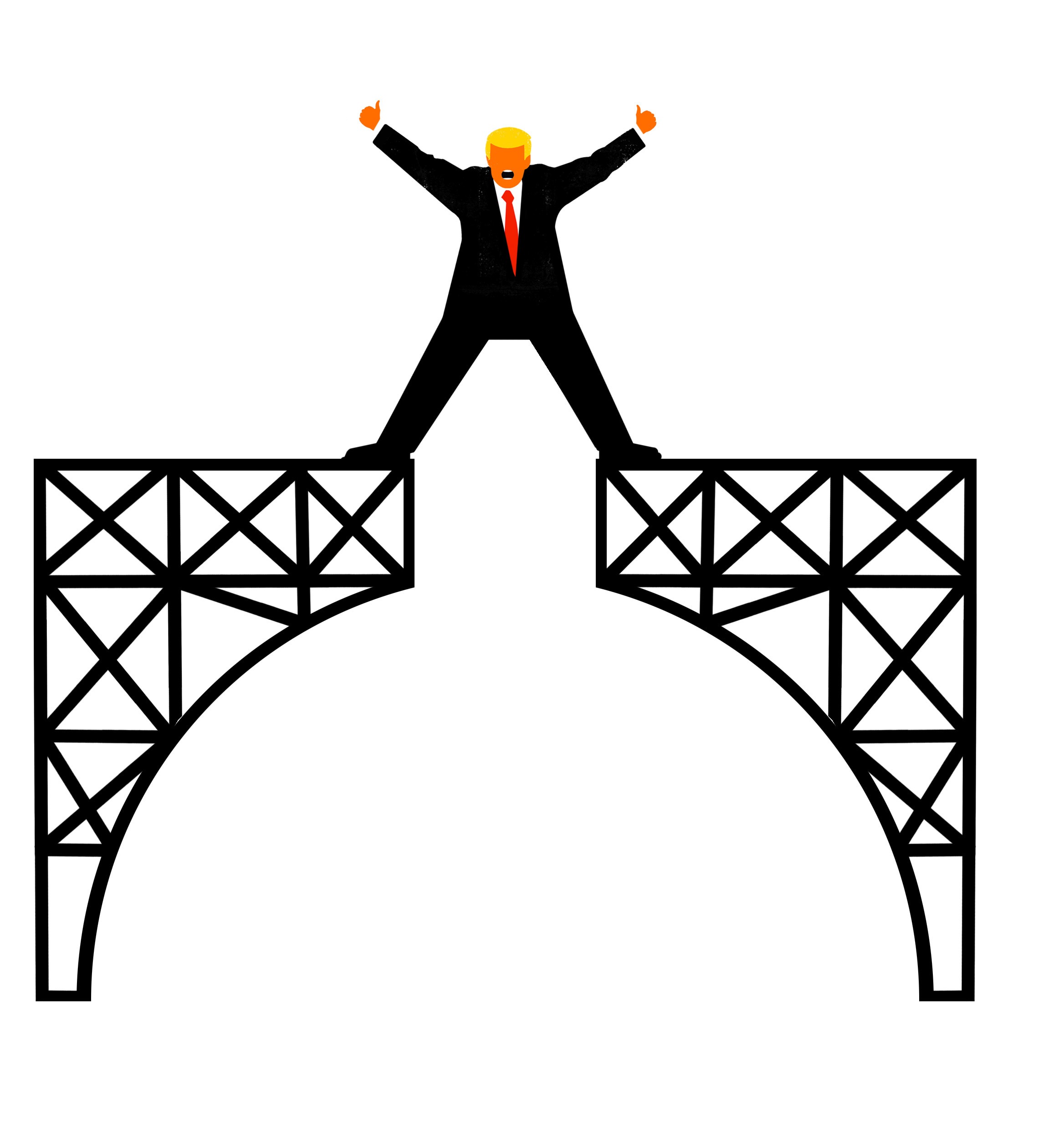

Fulfilling a campaign promise, President Trump revealed his long-anticipated plan to rebuild U.S. infrastructure in February. It calls for $200 billion in federal money that, he contends, will create $1.5 trillion in infrastructure spending. Government funds are to be spent as follows: $80 billion mainly goes to constructing new government office buildings and financing “transformative” ventures; $120 billion will be federal matching dollars for “approved” projects, with $100 billion going to state and local governments and $20 billion to private firms.

Given the magnitude of our problem, we should be happy to have a national infrastructure revitalization plan. However, this is a badly flawed plan that will do little to raise our D+ infrastructure grade or help average Americans. At bottom, it is another Trump giveaway to the rich. Here’s why.

Spending money for new federal buildings and transformative projects may give the president bragging rights, but it is a poor use of resources when there are more pressing needs, like improving water quality and sewage systems.

This is a badly flawed plan that will do little to raise our D+ infrastructure grade or help average Americans.

Firms receiving federal matching dollars will have to put up some of their own money. They will also have to earn profits. Because deficit concerns preclude more federal borrowing for this, the only option is that private firms be granted ownership of U.S. infrastructure. We will drive on roads, cross bridges, and fly out of airports that are privately owned. Firms will earn large profits, while citizens—who have already contributed their tax dollars to help launch the new projects—will pay dearly and continuously.

Also, it is unclear where the federal government will find $200 billion now that the 2017 tax bill has ballooned the federal deficit. Many people expect that existing infrastructure spending will be cut—for example, federal contributions to Amtrak and the Highway Trust Fund (mainly used for road repairs). Increasing federal infrastructure spending with one hand while cutting it with the other is just a shell game that will not improve road quality or transportation resources in the nation.

The plan is for federal money to go to states and counties that contribute 80 percent of project costs. Or the federal government will provide $1 for each $4 spent by state and local governments. The federal government’s $100 billion matching money, added to $400 billion from lower levels of government, in theory creates $500 billion in infrastructure spending.

To paraphrase P.T. Barnum, this part of the plan assumes that suckers are born in state government every minute. Currently, the federal government pays around half the cost of rail and mass transit projects and 80 percent of road and bridge projects. Why would local governments—already cash-strapped—jump at the opportunity to pay 80 percent of total project costs?

Even if they want to participate, state and local governments are not likely to come up with $400 billion, especially in poorer areas with great needs. The Republican tax bill passed last December makes it much harder for state and local governments to raise revenues. Interest on municipal bonds, the main source of local government infrastructure revenue, is not taxable. Lower tax rates for the rich make these bonds less attractive investments, which will force local governments to pay higher interest rates when borrowing. And since state and local taxes are no longer fully deductible on federal tax returns, struggling regional governments will be hard pressed to raise taxes to fund infrastructure projects. Only wealthy areas will be able to do this.

Even worse, if local areas apply for more than the $100 billion allocated for federal matching dollars, there will need to be some mechanism for deciding who gets money from the federal government. Trump gets things exactly backward here, as his plan stipulates that funding will go to areas that provide the largest sums of money. The question of where the money will do the most good is weighted at only 5 percent of the decision regarding who gets federal revenues.

Given our massive infrastructure deficit, we need to put money where it is needed most and where it will do the most good for the nation, rather than simply where people can pay the most for it. Trump’s decision-making criteria ensure that road and bridge repairs will be made in affluent communities rather than in areas where roads are in the greatest state of disrepair or bridges are in danger of collapsing. We will construct and expand airports that serve wealthy communities; places like Flint, Michigan, whose problems with contaminated water have attracted national attention and which face great difficulty raising additional revenues, will get passed over.

Finally, the president wants to “streamline” environmental review for all infrastructure projects. One agency, presumably filled with Trump appointees, will decide which projects can go forward. Environmental damage will not likely count for much—unless it affects the affluent communities that donate money to Republicans.

The only good thing that can be said about the president’s infrastructure plan is that it stands little chance of making it through Congress. Senators and Representatives will be under great pressure to oppose a plan requiring their states and regions to pony up more money. Democrats will oppose the plan because of environmental concerns and because it won’t help communities in greatest need. Even if all Republicans vote for the plan, nine Democrats would have to vote to end a Senate filibuster. If Democrats hold firm, this bad infrastructure plan, mercifully, will be derailed.

Steven Pressman is professor of economics at Colorado State University, author of Fifty Major Economists, 3rd edition (Routledge, 2013), and vice president of the Association for Social Economics.

Where was Obama’s plan?