They left that young man’s body lying in the street for more than four hours,” Anthony Bell said on a sweltering August afternoon on West Florissant Street in Ferguson.

The crowd was beginning to build for the nightly protests on what passes for Main Street in Ferguson’s black community, a four-lane stretch of bottom-dollar retail: Ace Cash Express, Crystal Nails, take-out Chinese, rent-to-own furniture, two grocery-liquor stores, all anchored by a Family Dollar store.

Bell had set up a tent, a table and a “Register to Vote” sign, and was working the protestors as they filed past. He told me he had received a call from Michael Brown’s family immediately after Brown was shot by Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson.

“They thought I could help with the police,” said Bell, a Democratic Party Party ward committeeman.

Bell arrived to find Brown’s body lying in the middle of the street, the area cordoned off by yellow police-line tape. He said he called Ferguson Police Chief Thomas Jackson and asked him to move the body from the street, and was told the body would be moved after a coroner arrived.

Bell called Jackson two more times and at some point an officer covered Brown’s body with a sheet.

“He was still laying there, with his feet sticking out from the end of the sheet,” Bell said.

Bell stayed on the curb watching over the body, he said, to ensure that the police didn’t plant a gun.

“Where in this country do you leave a young man’s body laying in the street for four hours?”

“Next thing, they put dogs on us. People were running. Little kids running from the dogs.”

Bell said the police chief would not allow any member of Brown’s family to approach the body.

Then Bell asked a question that tells you almost everything you need to know about the demonstrations and rioting that upended this suburban municipality of 21,000:

“Where in this country do you leave a young man’s body laying in the street for four hours?”

“Wilson Was Always Messing with Us”

Ferguson, Missouri, is an African-American community where the average individual income is $16,548, 27 percent of the population lives below the federal poverty level and 14.3 percent of the population is unemployed.

Despite the poverty and unemployment, Ferguson’s municipal court took in $2,635,400 in 2013, the incorporated suburb’s second-highest revenue source. Astonishingly, municipal court judges disposed of 24,532 warrants and 12,018 cases. That’s roughly three warrants and 1.5 cases per household, according to a white paper published by the public interest law firm Arch City Defenders.

Most of the revenue is extracted from the Ferguson’s black population; 86 percent of police stops were of blacks. And 92 percent of searches and 93 percent of arrests by Ferguson’s police were of African Americans.

The statistics tell only part of the story. There’s no municipal revenue in the routine police shakedowns when no arrests are made. “Where we stay, it’s normal to see a young black man lying on the ground during a traffic stop,” Audre Lind told me.

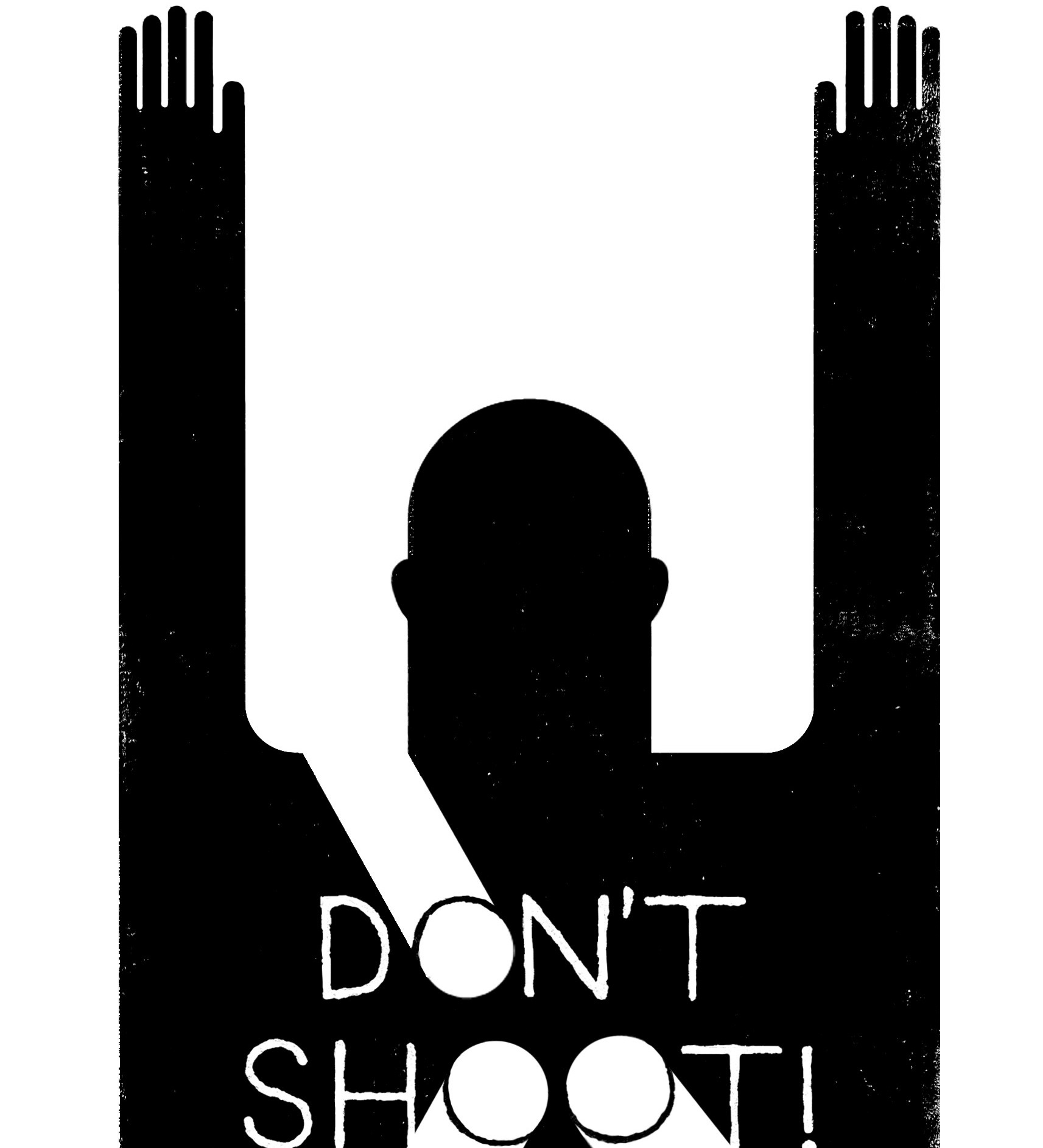

Lind, in her sixties, was in the line of protestors on West Florrissant, carrying a “Hands up for Jesus” sign—a variation on the “Hands Up! Don’t Shoot!” signs carried by many protestors.

“These young men are tired of being disrespected.”

Canfield Green Apartments, a 400-unit island of poverty surrounded by a more prosperous suburban neighborhood, is situated on the same block as the Northwind Apartments where Brown’s grandmother lives.

Over the course of a week, I interviewed 16 young men and six young women in the two complexes.

One woman, Trina White, told me she had been stopped by the same officer who killed Brown.

“That was in the week before the QuickTrip [was] burned [by looters],” she said. “I had my kids in the car.

“Wilson was always messing with us.”

White and her husband have decided to leave Ferguson.

1,000 Humiliations

All but one of the men I spoke to had been stopped by a white police officer at least once. Only one had been arrested. Seven men said they had been handcuffed, nine said their cars had been searched. Lavaun Williams’ story was typical.

Williams had left Canfield Green two years earlier, he said, because his wife couldn’t live with gunshots at night. While he lived there, he was twice stopped by police. “First time, the cop pulled me over and said, ‘Do you have a gun?’”

“I don’t carry a gun. And I don’t smoke [marijuana],” he said.

Williams, a strikingly handsome, dark-skinned young man dressed in a T-shirt, shorts and sneakers, looked like anything but a gang-banger.

“I had a nice car, a 1984 Audi. They had no reason to suspect anything. They made me get out and put handcuffs on me and searched the car. I had no warrants, no police record. I was going to work at McDonald’s. They took the handcuffs off and said, ‘You’re free to go.’”

“The next time they stopped me, it was the same thing. But I had my son with me. My son was crying. I was embarrassed. They put me in handcuffs, went through my car, then said, ‘OK, you can go.’”

“I’m not a criminal,” he said. “I’m the manager of a Taco Bell.”

Talk to almost any African-American man under the age of 30 on Canfield Street and you’ll hear a similar story.

If the cop who killed Michael Brown is not indicted, look for Ferguson to light up again.

The Justice Department is conducting an investigation of Ferguson’s Police Department. And a grand jury is scheduled to decide this month whether the officer who shot Brown will be indicted. If he is not, look for Ferguson to light up again.

What happened in the weeks following the killing of Michael Brown was a response to a thousand accumulated humiliations. White policemen believe they have to keep young black men in line. That’s what Darren Wilson was doing when he saw Michael Brown walking down the middle of the street his grandmother lives on in the middle of an August day in Ferguson.

Democratic state Senator Maria Chappelle-Nadal gets it. Chappelle-Nadal, a woman with a radiant smile, stylish Afro and a cut-to-the-chase attitude, was a magnet for TV cameras.

But she was out in the neighborhood talking to kids on the street after CNN and MSNBC had packed up and moved on.

I talked to her on the lawn of a Canfield Green apartment.

“These kids for their entire lives have been disrespected, insulted and abused by police. Disrespected by authority.

“No jobs. No hope. They are constantly targeted by police for the most minor thing. For nothing.

“Then they see one of their homies laying dead in the street. They look at him and they see themselves.”

Lou Dubose is the editor of The Washington Spectator.

The murder of Mr. Brown is a further example of our police administering extreme force, as opposed to other containment measures. We use tranquilizer darts to stop animals and bullets to stop people.

I understood from the media, that the body had to be left undisturbed because the forensic team was finishing up on another case miles away.

The court room revenue statistics are very compelling. It is obvious that the civic managers of Ferguson are intent on systematically keeping their African American neighbors as poor as their laws allow.

I hope Mr. Bell is new to his registration job, as the African American voter turn out in Ferguson, is under 6% according to one statistic I read. As bad as things are in Ferguson, not voting is voluntary self-suppression.

J Felsot