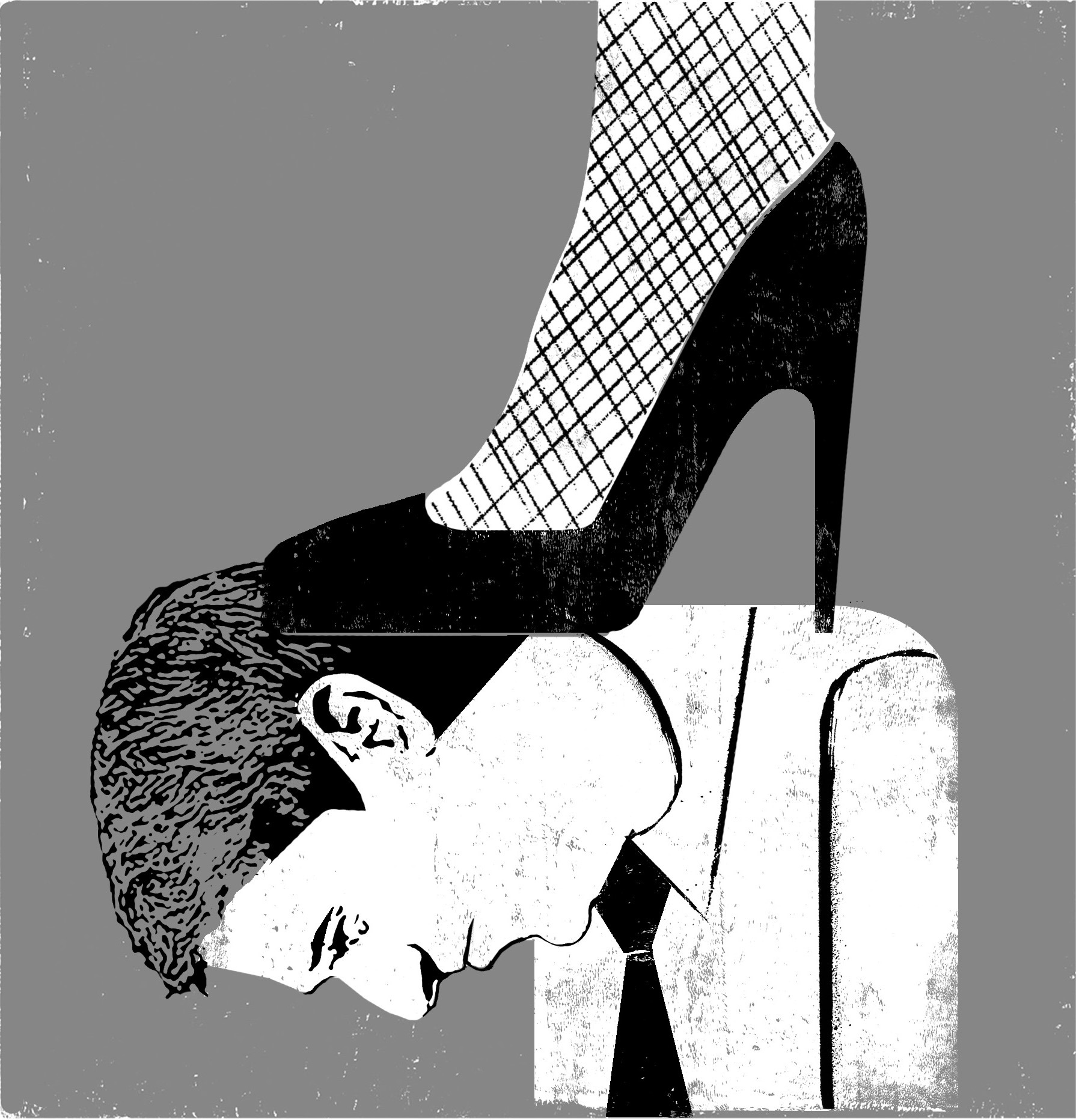

Illustration by Edel Rodriguez

How did a little-known Democratic state representative manage to win a landslide election for governor in deep red Louisiana?

Easy. John Bel Edwards drew the reviled U.S. Senator David Vitter as his opponent.

That’s not great news for Democrats hoping that Edwards’s stunning 56–44 November 21 victory would illuminate a path in other challenging environments. Vitter, a political juggernaut for most of his 24-year career despite a prostitution scandal that would have destroyed a less talented—and less brazen—politician, collapsed in epic fashion. Edwards’s smart, character-based campaign certainly helped, but the election boiled down to a referendum on the archconservative Republican senator, who saw the writing on the wall and announced during his concession speech that he wouldn’t seek a third term in 2016.

Outside of Edwards’s initially small circle—his family and friends, some deep-pocketed trial lawyers, and organized labor, particularly teachers’ unions—few would have predicted the outcome when the season began. With Governor Bobby Jindal AWOL in Iowa running his futile presidential campaign, Vitter was Louisiana’s most powerful, best-funded Republican. No Democrat had won statewide since 2008. Vitter himself easily won reelection in 2010 by fixating on Obama, at the height of Tea Party fervor and three years after news broke that Vitter’s phone number had appeared in the records of a Washington, D.C., call-girl ring.

In one ad, Edwards zeroed in on a Congressional vote honoring fallen soldiers that Vitter missed on the same day he received a call from the prostitution ring. Vitter chose “prostitutes over patriots,” the narrator intoned.

This time, though, it was all about him. And that proved fatal.

It was also pretty entertaining. Louisiana elections don’t always rise to their reputation for theater, but this one delivered.

Vitter, equally famous for his scorched-earth tactics and his prickly, sanctimonious streak, left Edwards alone in the nonpartisan primary, on the theory that he’d be easy to dispatch once two other Republicans, Lieutenant Governor Jay Dardenne and Public Service Commissioner Scott Angelle, were out of the picture. But his decision to aim his guns at his fellow Republicans in Louisiana’s unique wide-open primary failed. He drew just 23 percent to Edwards’s 40 percent, and a pro-Edwards super PAC ad replaying his GOP opponents’ angry debate retorts set the tone for the four-week runoff campaign.

“He’s ineffective. He’s vicious. He’s lying,” said Dardenne, a straight-arrow who could barely control his fury after Vitter ads attacked his ethics. (He backed Edwards in the second round.)

“We have a stench that is getting ready to come over Louisiana if we elect David Vitter as governor,” added Angelle, who had taken to referring to Vitter as “Senator Pinocchio.”

Vitter’s more distant past came back to bite him too. On the eve of the primary, a private investigator working for Vitter got caught surreptitiously recording a coffee shop conversation of a small group that included another private eye trying to dig up dirt on Vitter and a wealthy Edwards donor. Unfortunately for Vitter’s hapless spy, the coffee shop at that moment also hosted an attentive Newell Normand, the popular Republican sheriff of Vitter’s home turf in Jefferson Parish, and a political foe since Vitter’s earliest days in politics. A livid Normand arrested the spy, turned over his surveillance equipment and recordings to the FBI, and cut an ad declaring Vitter all about himself.

Then there was Jindal, who picked election week to give up his presidential quest, head home, and hijack the headlines. Many insiders saw his timing as payback for the week in 2007 when Vitter’s prostitution story broke (Jindal offered only tepid support), and Vitter and his wife Wendy stepped on Jindal’s gubernatorial announcement by scheduling a press conference the same afternoon.

And don’t discount Edwards himself, a West Point graduate who skillfully defused allegations that he was too liberal for Louisiana, kept the focus on integrity, and turned out to be just as battle-ready as Vitter. In one ad, he zeroed in on a Congres- sional vote honoring fallen soldiers that Vitter missed on the same day he received a call from the prostitution ring. Vitter chose “prostitutes over patriots,” the narrator intoned. During a free-wheeling debate, Edwards countered Vitter’s criticism of his lifetime 27 percent rating from the state’s main business lobby like this: “I give 100 percent to my wife . . . Senator, you ought to try it.”

Through the frantic runoff campaign, Vitter struggled to regain his equilibrium, to little effect. He relentlessly linked Edwards to Obama, even though the two had never met. He dressed in camo and appeared with Duck Dynasty’s Willie Robertson in one of several redemption-themed ads. In another, he reminded voters that “you know me,” which, of course, was precisely the problem.

Still, despite all the ways in which the Louisiana gubernatorial was a one-off, there are some lessons to draw.

One is that candidates matter, particularly for state rather than national office. Edwards, who hails from a small town an hour north of New Orleans, was conservative enough on abortion and gun rights to give many voters a level of comfort. His military background and support from law enforcement helped, too. (Edwards comes from a long line of Tangipahoa Parish sheriffs, a job his brother now holds.) The fact that voters didn’t know much about him allowed him to keep the focus on Vitter, a feat that a higher-profile Democrat such as New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu might not have pulled off.

Just as important, the economically populist issues he pushed didn’t set off alarms. Edwards championed Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act, which Jindal refused to consider. He also backed a modest increase in the state minimum wage and pay equity for women. These positions aren’t necessarily deal-killers in conservative states.

Yet another lesson is that the bad aftertaste of Jindal’s eight-year tenure, marked by chronic budget woes and punctuated by a recent poll giving him a 20 percent approval rating, may well have carried over to Vitter. Sure, they hate one another, but both are rigid ideologues, and both seem willing to do whatever it takes to win. So when a decent guy came along—one who promised voters that he would always be honest with them and never embarrass them—they gave him the benefit of the doubt.

Maybe the takeaway is that sometimes it’s enough just to offer people a change of pace. You never know when they might be ready for one.

Stephanie Grace is a columnist for The New Orleans Advocate.

Excellent analysis – right on target.