On the surface, the U.S. Supreme Court’s evisceration of the Voting Rights Act and the national non-discussion on poverty have little in common. The former is about whether the racially discriminatory history of certain parts of the country merits their being placed under special scrutiny when it comes to how they shape their 21st-century ballot access rules; the latter is about inequality and social justice. They are two separate stories about two distinct American phenomena.

Yet, I would argue, these two are intimately linked.

In my soon-to-be-released book, The American Way of Poverty, I chronicle the lives of America’s poor and marginalized. Some, such as one-time sheet-metal worker Matthew Joseph, were out of work and struggling to pay housing bills, find health insurance, and feed their families when I talked with them; others, such as Wal-Mart worker Mary Vasquez, an elderly lady with a laundry list of physical ailments, had work but were paid abysmally low wages. Some of the people I write about are young and deeply in debt because of student loans; others are older and equally deeply in the hole because they were pressured into taking out subprime mortgages. Some live in slums; others in suburban McMansions. Some are white, some are black, some are Latino, some are Asian, some are Native American.

| That a majority of Supreme Court justices could, with straight faces, say systemic racism is a thing of the past shows a stunning lack of empathy. |

Over the course of two years, as I reported the book and interviewed hundreds of people around the country, I came to have an appreciation of both the diversity of poverty in contemporary America, and also the deeply corrosive impact that spreading economic hardship has on the body-politic. For, as the broader economy was hollowed out in the years surrounding the 2008 financial implosion, so an increasing number of people began failing to meet their most basic economic needs.

One in six Americans, or about 50 million people, is now so economically insecure that they rely on food stamps to avoid hunger. Roughly one in five children live below the poverty line in this most wealthy of countries—a country with more billionaires than any other, and one in which well over 90 percent of all income gains in the past couple years have gone to the wealthiest one percent of the population.

Six million Americans have literally no cash access, living hand-to-mouth on food handouts and charity. And in cities such as Detroit and New Orleans, African-American child poverty reaches surreal heights. Sixty-five percent of African-American kids under the age of 5 in New Orleans live below the government-defined poverty line. In colonias in the southwest, undocumented migrants live in cardboard and scrap-metal shanties, often with no electricity, no sewer lines, no running water. In many inland counties in California, despite our ostensibly being four years into a recovery, unemployment rates still top 15 percent.

While poverty transcends race, a disproportionately high number of African Americans and Latinos in this country live in poverty, and the more intense the poverty the more the data becomes racially skewed.

As for household wealth, while white families have always been far wealthier, on average, than black families, the housing market bust massively magnified these trends. In 2011, the Pew Research Center found that white families’ median wealth was 20 times that of blacks and 18 times that of Latinos. The subprime mortgage debacle wiped out decades of wealth accumulation for minorities; three years into the bust, the median household wealth of black families was less than $6,000.

And since, in America, the wealthier one is the more likely one is to vote consistently from one election cycle to the next, and the poorer one is the less likely, what we see here is an ongoing political as well as economic crisis. Sure, in some elections—notably the last presidential one, in 2012—some of this data is turned on its head; but averaged out over the years, these trends hold fairly constant.

| Too many people are essentially being told by the most powerful institutions in the land that their voices don’t count and their stories don’t matter. |

Magnifying this is another issue that I have written about for more than a decade now: felon disenfranchisement. More than 5 million Americans cannot vote because they are either currently in prison or on parole, or because they live in states—most of them in the Deep South—that still impose lifetime prohibitions on voting for people convicted of felonies. America incarcerates a far higher proportion of its population than any other country on earth—and, again, disproportionately this burden falls on African Americans and Latinos. Nearly one out of every 20 black men in America lives behind bars. In some Southern states more than one in five African-American men have lost the right to vote. The Hispanic incarceration rate is lower than that for African Americans, but still roughly double that of whites.

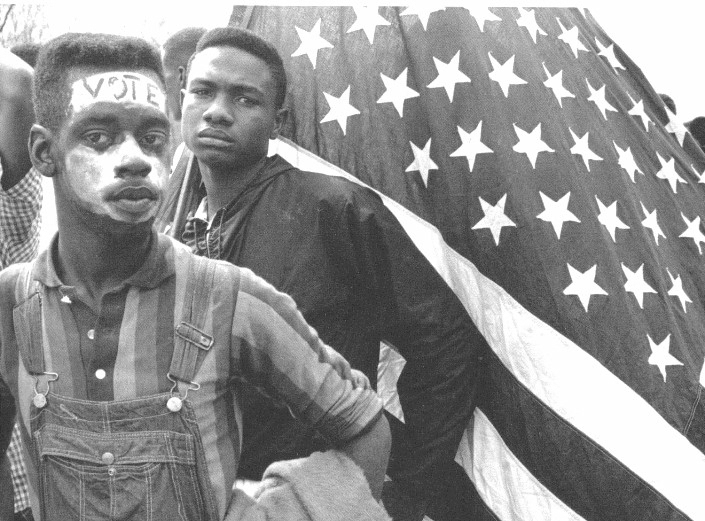

All of which ought to have given the Supreme Court huge reason to pause before dismantling the Voting Rights Act and the core protections embodied in it for nearly the past half-century. By every measure, removing these protections will make it harder for poorer Americans to vote; and, because of the distribution of poverty in this country, will make it peculiarly hard for poor African Americans and Latinos to exercise the franchise.

Chief Justice John Roberts and his four confreres may be right that America is no longer living through the overt race-baiting era embodied by Bull Connor or George Wallace; but that doesn’t mean the country as a whole has somehow entirely gotten beyond its sorry racial history. Yes, at the federal level the president and the attorney general are African American. But that reality hasn’t stopped anonymous leaflets being distributed in poor black communities in recent election cycles telling residents that the date of the election has been changed; nor has it stopped gerrymandering that looks suspiciously like it is designed to minimize African American voting strength in several states; nor has it prevented the circulation of rumors in poor communities saying that not only are felons disenfranchised but so too are all people convicted of misdemeanors—or, in some instances, that even an outstanding traffic ticket is enough to remove a person’s right to vote.

That a majority of Supreme Court justices could, with straight faces, say that systemic racism, in all its complexity and in all its many manifestations, is a thing of the past shows a stunning lack of empathy. That same lack of empathy is seen when defenders of restrictive voter I.D. laws say that it’s easy for everyone who wants I.D. to get it. It is also seen in the remarkable absence, from the recent national dialogue, of a detailed discussion of modern-day American poverty and its impacts on the lives of millions of Americans.

Too many people are essentially being told by the most powerful institutions in the land that their voices don’t count and their stories don’t matter. It is past time for a politics of empathy to once again take center-stage in this country.

Sasha Abramsky is the author of several books, including Inside Obama’s Brain and Breadline USA: The Hidden Scandal of American Hunger and How to Fix It and the forthcoming The American Way of Poverty

0 Comments