If you want to know where the Republican Party is headed, you need to set aside your assumptions and simply listen to what its leaders and activists say—especially when they’re talking amongst themselves. As a reporter and author on the religious right beat over the past dozen years, I’ve made a point of attending such meetings, especially those that focus on the religious right leadership and strategists who command the movement’s voter turnout machine. Lately, I’ve been hearing things that might surprise—and alarm—those who see the movement only from a distance.

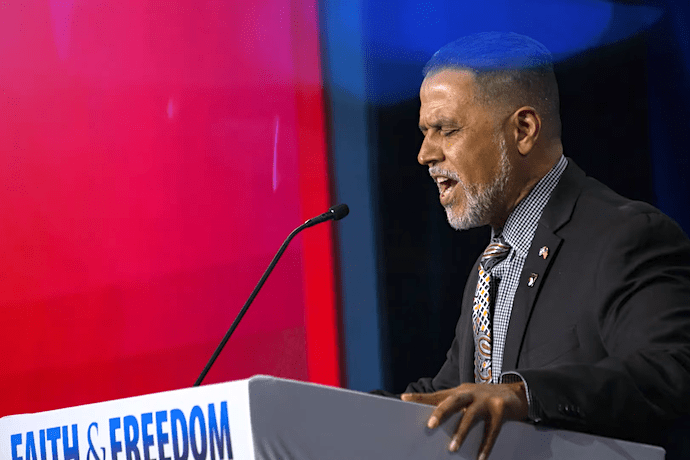

A good venue to catch up on the latest thinking inside the movement that wants to “take America back” to a place that never existed is this summer’s Road to Majority convention, an annual gathering of the Faith & Freedom Coalition, which was held this year at the Gaylord Palms Resort & Convention Center in Kissimmee, Florida.

In recent years, the convention has brought together the big Republican names with the on-the-ground activists who delivered the largest and most reliable slice of the Trump electorate. Dozens of featured speakers this year included Mike Pence, Ted Cruz, Marsha Blackburn, Ron DeSantis, Lindsey Graham, and Madison Cawthorn.

I came away from my listening experience in Kissimmee with a few surprises—or at least a few takeaways that may challenge some of the narratives that prevail in the center and on the left about America’s Christian nationalist movement. The first is that any Democrats who take comfort from the thought that demography is destiny are probably deluding themselves. The received wisdom on the center-left is that America’s homegrown authoritarian faction is an affair largely concentrated on an older, whiter base that is just now exiting the stage of history with loud grievances in hand. But that’s not how the leaders of the movement see things—and the broader picture may indeed be a bit more complex.

Of the many religious-right strategy gatherings I’ve attended over the years, this was among the most ethnically and racially diverse. “I am pleased to be able to report that we have 200 African American pastors and community organizers who are here this week and over 500 Hispanic pastors and community organizers, and we are going to keep going until this movement embraces the full diversity of our country,” said Ralph Reed. By my count, over 30 of the roughly 70 speakers were Black or Latino.

The diversity on display at the conference reflects the fact that the religious right has been making a sizable effort to cultivate conservative-leaning Latino and Black voters of faith. Much of the action starts by attracting religious leaders from communities of color, who are often drawn into larger pastoral networks such as Watchmen on the Wall and Ministeros Hispanos. An aspect of the diversity push, to be sure, is merely performative, a means of reassuring white voters that they aren’t racist after all. But the strategy works with a nonnegligible number of voters of color, too. Between 2016 and 2020, Trump made substantial gains among Latino voters in particular.

In Kissimmee, the speakers, and especially the speakers of color, had a unified message about race, and it was one that Democratic strategists might wish to note as they craft their own messaging and outreach in the run-up to the 2022 midterm elections. Speaker after speaker at the Road to Majority Policy Conference asserted that they believe in an America where race doesn’t define you—where opportunity is there for all who strive for it.

Never mind the Republican Party’s efforts to promote McCarthyist laws that restrict discussions of the history of racism and other supposedly “divisive concepts” in American schools; or its leadership’s denigrating characterizations of political leaders of color with whom they disagree. And who here really cares that the Republican Party has championed voter suppression and gerrymandering that disproportionately affect voters of color and others in democratic-leaning districts, or that some Republican leaders tolerate or even court the support of white supremacists? The fact is, this message has presumably convinced some people—including those at the gathering in Kissimmee—that their party is the one on the side of equality and justice for all, while the other side is the one that insists on characterizing everybody by the color of their skin.

C.L. Bryant, a right-wing television and radio host, made the point with an anecdote about a long-ago confrontation with his grandfather over his “Afrocentric” style. “He said these words: ‘Sonny . . . I didn’t go through all that I went through so that you could be Black. I went through all that I went through so that you could be free.’”

It’s a message that has a strong appeal to some immigrants, as Jennifer S. Carroll, a former Navy commander born in Trinidad who served as lieutenant governor of Florida, made clear at a panel titled “Majority Minority.” “I wanted to give back to my country because my country gave myself and my family so much,” said Carroll. “And that’s what immigrants are all about. Recognizing that this country is a special place. The only place in the land that can give a person like me the ladders to climb if I choose to climb it.”

Carroll delivered her comments with passionate sincerity. But as one speaker after another offered the same caricature of “critical race theory” as the centerpiece of their presentations, I was reminded of statements from Christopher F. Rufo, a conservative activist and architect of this new front in the culture wars: “We have successfully frozen their brand—‘critical race theory’—into the public conversation and are steadily driving up negative perceptions,” he wrote on Twitter. “The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think ‘critical race theory.’ We have decodified the term and will recodify it to annex the entire range of cultural constructions that are unpopular with Americans.”

At a Conservative Political Action Committee (CPAC) conference the following month the drumbeat continued. “What are our parents around the country doing to stop critical race theory from taking over our schools, what are we doing to stop them from taking over our corporations, taking over sports, even taking over the military?” said David M. McIntosh, president of the Club for Growth. “Martin Luther King had a dream: that we would judge or be judged by the content of our character and not the color of our skin. . . . But radical Marxists have taken over this movement they call critical race theory that shames our children, treats them differently and punishes them based on the color of their skin. And tells them America, our country, our capitalist free markets, our constitution are evil and irretrievable.”

According to a June report in Media Matters, in the prior three and a half months, “critical race theory” was mentioned on Fox News nearly two thousand times. By comparison, in November 2020, there were just four mentions.

The second surprise on my listening tour was more of the I can’t believe this is actually happening variety. Over the past two decades, the imminent demise of the religious right has been predicted with casual confidence many times, and the often unspoken assumption is that the movement will turn watery as it fades away. But that isn’t what the people at the Road to Majority conference or CPAC think at all. This movement is getting ideologically harder, hotter, and more extreme in every way as it moves forward into the future.

Two decades ago, an ideology called “Seven Mountains Dominionism” was considered so fringy that it was never allowed near the podium with Republican political leaders. Now, that very same ideology is a heartbeat away from everything that happens in the Republican Party. This year, in fact, the Road to Majority featured a breakout session titled “The Seven Mountains of Influence.”

Seven Mountains dominionism is the conviction that Christians of a certain hyperconservative variety should rightfully dominate the main peaks of modern civilization in the United States and, ultimately, the world. The ideology reportedly got its start in 1975, when Loren Cunningham, a missionary leader, and Bill Bright, the founder of Campus Crusade for Christ (now known as “Cru”), allegedly heard messages from God urging them to invade the “seven spheres” of society, which by their reckoning included government, media, education, business, entertainment, religion, and family. According to the late C. Peter Wagner, a key proponent of the ideology, the responsibility of Christians to take over “whatever molder of culture or subdivision God has placed them in” is really a matter of “taking dominion back from Satan.”

That last bit about Satan gets to the throbbing heart of this political ideology. In Kissimmee, speakers and panelists inveighed that America is “on the precipice,” careening toward a “socialist revolution,” “anarchy,” and “chaos, and is under the thumb of the most despicable human beings imaginable—namely Democrats, who were referred to as “the enemy,” “Satanic,” and “agents of evil.” Panelist and religious activist Johnny Enlow, who has authored multiple books on the “Seven Mountains,” warned that if Christians don’t fight to “conquer darkness,” the world goes “under control of the deep state, illuminati, demonic possession for hundreds of years, that’s what we’re facing.”

Describing what she claimed to be a Democratic voter registration operation targeting Puerto Ricans coming to America after Hurricane Maria, Adianis Morales Robles, a GOP operative and religious right activist, said, “God was showing me the injustices that these organizations, these demonic organizations, are doing to our people.”

For decades, this kind of blatantly theocratic political ideology lived on the fringes of the Republican Party, where leaders might toss its adherents a gratifying wink while pretending to the outside world that they didn’t really exist. Those days are over. In Kissimmee, at the conclusion of “The Seven Mountains of Influence” breakout session, comprised entirely of panelists of color, Ralph Reed stopped by to offer praise and encouragement. “I want you to know that my commitment to building bridges in the African American community is not about politics,” he said as dozens of attendees rushed toward the stage to get selfies with the speakers. “This is about the Kingdom of God.” Other speakers and panelists at the Road to Majority convention invoked the language and goals of Seven Mountains dominionism as if it were simply shorthand for the Republican agenda.

“You got to put on the full armor of God,” said Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, alluding to a passage from Ephesians that’s often used to invoke a “spiritual war” against the devil. “You got to take a stand, take a stand against the left’s schemes.”

The end-of-the-world vision at the heart of the new Republican orthodoxy may help explain a further observation: The people who attend these kinds of religious nationalist gatherings—the activist backbone of the Republican Party—are in no mood to back down from the January 6 attempt to subvert the presidential election through a brutal and disgraceful attack on our Capitol. Sometime around January 7, some parts of the mainstream wisdom coalesced around the idea that the Republican Party now had a chance to separate itself from the anti-democratic elements within. That moment has passed. There will be no reckoning within the Republican Party over Donald Trump’s attempted coup, and any Republican who tries will be excluded from gatherings like these.

In conversation with conference organizer Ralph Reed, Eric Metaxas let it be known that the real victims of the January 6 event were the good people who ransacked the Capitol. He fired “an arrow across their bow” (his words) to Republican leaders: “Any Republican that has not spoken in defense of the January 6 people to me is dead. They’re dead.”

The right-wing political commentator and activist Dinesh D’Souza, also in conversation with Ralph Reed, echoed the sentiment. “The people who are getting shafted right now are the January 6 protesters,” he said. “We won’t defend our guys even when they’re good guys.”

Reed nodded and replied, “I think Trump taught our movement a lot.”

At CPAC, January 6 was even reconceived as a possibly Democratic plot. “[The Biden] administration is about tyrannical rule. They don’t follow the Constitution,” said Allen West, former chairman of the Republican Party of Texas, before he recast events driven by far-right extremists as bizarre and possibly Democratic conspiracies. “On January 6 the sergeant at arms had turned down, on behalf of the speaker, having the National Guard there to help protect the Capitol. Why did that happen? You think they were setting things up? Well I do.”

In Kissimmee, perhaps the sole wry note of commentary on the character of the former president was provided by Senator Lindsey Graham, who quipped, “We came to find common ground. The common ground is that [former president Trump] likes [himself], and I have come to like him,” But I heard no expressions of remorse, misgivings, or even doubt about the greatness of Donald Trump and his administration. “Bottom line is President Trump delivered, don’t you think?” Graham concluded. This party—or at least the hard rock of its base represented in this gathering—is moving toward, not away from Trumpism.

And yet, notwithstanding the apocalyptic rhetoric and visceral hatred of the liberal enemy that seemed to exude from every presentation and panel (Democratic strategists take note), this is a party and movement that is determined to telegraph confidence in the future and tell a positive story about America. I’m going to count this as something of a surprise, too—because the conventional narratives on the left hold that any movement so steeped in fear and loathing cannot possibly have a positive mindset, and that narrative turns out to be false, at least to the people here on the ground.

Speaker after speaker told hopeful stories of personal triumph and presented a vision of an America characterized by what they call “freedom,” opportunity, personal empowerment, and spiritual fulfillment. Party loyalists in Kissimmee passionately conveyed the message that this happy future is within their grasp—they just need to trample a few “demonic organizations” to get there.

A final aspect of today’s Christian nationalism that deserves more attention than it gets is the role of extreme money in shaping the movement. Too often the nature and goals of the movement are explained—and explained away—in purely social terms, as the reactions of a large mass of believers who see the world of their youth slipping away. We too easily forget that building an effective political movement of this kind takes a lot of money—and that money isn’t shy about speaking its mind.

A good place to witness the union of money and God would surely have been the Ziklag Group gathering, which took place at the Omni Shoreham Hotel in Dallas in mid-June.

Named after a Philistine town that biblical King David used as a retreat from which to mount his battle against the Amalekites, the Ziklag Group is affiliated with United in Purpose, a data, networking, and messaging organization that’s played a substantial role in turning out the conservative Christian vote in past elections. You can get a sense of the Ziklag Group’s true raison d’être from a glance at its “membership/attendee criteria,” which appeared on the invitation. Attendance, I learned, was limited to those who are “committed to Christ,” are “humble in spirit,” and have “demonstrated success in business with significant financial means, defined as a net worth of at least $25 million.”

Having come up, among other things, a few million dollars short on their admissions requirements, I can’t offer any takeaways from the Ziklag Group’s gathering. But the invitation I saw showed that, just like the Road to Majority gathering in Kissimmee, it prominently featured a Seven Mountains Mandate workshop along with its list of noted keynote speakers including Mike Pence.

But one difference between the gatherings in Kissimmee and Dallas has to do with the certainty of payoffs. Whether the tax cuts, budget cuts, and non-regulation of markets that are the reliable outcome of Republican politics will work to the benefit of the diverse crowd that gathered in Kissimmee is doubtful. That they will serve the interests of the extravagantly rich attendees of the Ziklag Group gathering, on the other hand, is certain. That, presumably, is why the kind of people who attended the event in Dallas are likely footing most of the bill for events like these that unite the Republican Party around a radical vision, even as they deepen our country’s political divisions.

Katherine Stewart is the author of The Power Worshippers: Inside the Dangerous Rise of Religious Nationalism (Bloomsbury). Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The New York Review of Books, and The New Republic. This article was originally published by Religion Dispatches, a publication of Political Research Associates, on August 9, 2021.

0 Comments