The federal income tax this week turns a century old. On October 3, 1913, President Woodrow Wilson signed into law the first modern federal tax on income.

John Buenker has been writing about the events—and attitudes—that led to that signing for a good bit of the last 50 years. His 1985 book, The Income Tax and the Progressive Era, remains the single most insightful history of the years of struggle that led to federal income taxation.

That history clearly matters to Buenker, an emeritus historian at the University of Wisconsin-Parkside. But should this history also matter to the rest of us?

Actually, the history of the income tax may matter more today than ever before. Here in 2013, after all, Americans face almost the same exact challenge our counterparts in 1913 faced. They lived amid a staggeringly intense concentration of wealth and income. We do, too.

Today’s plutocrats, in fact, strike Buenker as even “more dangerous than the Robber Barons of yore.”

| Exactly a hundred years ago, decades of progressive struggle finally paid off and outfitted America with a tool for braking the unlimited accumulation of private wealth. |

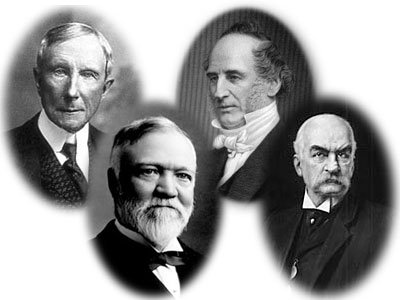

The Rockefellers, Carnegies, and their ilk, the veteran historian told Too Much last week, could certainly be vicious. But these plutocrats had to “moderate their actions,” at least to some degree, because they needed U.S. workers and consumers. Their plutocratic wealth sat largely rooted in America’s “factories, mines, machinery, and transportation networks.”

Today’s wealthy have no such roots.

“With globalization, outsourcing, off-shore schemes, and ‘free trade’ agreements,” Buenker points out, “today’s ‘masters of the universe’ operate virtually beyond the reach of even the most progressive of governments and powerful of unions.”

Even so, America’s original plutocrats a century ago did wield formidable power. The world had never seen fortunes as massive as theirs, and America’s deepest pockets seemed to enjoy nearly a lockgrip over the nation’s politics.

U.S. senators back then never had to stand before voters. State legislatures, not average Americans, decided who served in the Senate, and the state lawmakers who filled these legislatures often considered corporate giants their only constituents who mattered.

And should legislation hostile to plutocratic interests somehow slip into law, the Supreme Court stood ready to rescue the nation’s most comfortable. In 1894, with the west and South aflame in populist revolt, Congress passed a modest income tax on America’s affluent. The Supreme Court the next year declared the tax unconstitutional.

Americans of modest means, despite this stacked political deck, would eventually prevail over America’s plutocrats in the battle to tax high incomes. Growing economic hardship, historian John Buenker believes, certainly played a key role in this victory.

The depression of the mid 1890s, the sharp inflation of the early 1900s, and the financial panic of 1907 all nurtured growing public unease over the political and economic domination the rich exercised over American life.

But this growing unease, Buenker observes, only translated into an income tax because progressive activists had spent decades on the “frustrating, brutal, and boring work” of building a “multifaceted, nationwide coalition” committed to taxing the rich.

“They kept grinding away against all that wealth and power,” says Buenker. “They refused to give up, no matter how many barriers their opponents threw in their path.”

Conservatives in Congress threw up the last major barrier in 1909. Challengers of plutocracy that year finally appeared to have enough votes to put an income tax into law. But a series of cynical congressional deals sent to the states instead a constitutional amendment that only gave Congress the authority to consider income taxation sometime in the future.

Conservatives felt sure this amendment would never gain enough states to win ratification. They would be unpleasantly surprised. In 1910 and again in 1912, progressive groups mobilized to elect pro-income tax state legislative majorities in state after state.

The 1912 elections also gave Congress pro-income tax majorities in the House and Senate, and these majorities would welcome the newly ratified income tax amendment and move expeditiously to act upon it.

That first income tax statute lawmakers sent to Wilson in 1913 wouldn’t amount to much more than a nuisance for America’s rich—no dollar of income faced more than 7 cents in tax—but tax rates on high incomes would go on to rise significantly in the years to come.

By mid-century, Buenker says, the income tax had become the federal government’s “most effective tool for dealing with the obscene maldistribution of income and wealth.” By 1944, the tax rate on income over $200,000 had jumped to 94 percent, and the nation’s top tax rate would hover around 90 percent for the next two decades, years of unprecedented middle-class prosperity.

Buenker started researching all this as a grad student in the mid 1960s. Back in those years, he remembers, historians took the income tax as a done deal. They saw progressive income taxation as a basic reform that had helped permanently transform the United States.

These historians a half-century ago never imagined the massive conservative counterattack that would soon start blindsiding the reforms of the Progressive Era, New Deal, and Great Society.

“I guess,” Buenker says, “we were living in something of a ‘fool’s paradise.’”

Given this conservative drive to “repeal the 20th century,” what would Buenker do differently if he were writing his income tax history today? “I would go into much more depth in researching the dynamics and mechanics of building the multifaceted, nationwide coalition that brought the income tax into effect.”

The lesson from that coalition? Achieving success against concentrated wealth and power, says Buenker, “takes persistence over a long period of time.” We need, he believes, to show that same persistence today in the struggle against America’s contemporary plutocracy.

“We need to keep plugging away because trying to change things protects us from accepting them,” the historian adds.

And Buenker, for his part, will keep plugging.

“As a grandfather and great grandfather,” as he puts it, “I don’t want my progeny to inherit the world that the Koch brothers, Fox News, and the Tea Party want to force upon them.”

Sam Pizzigati is an Associate Fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies and editor of Too Much: A Commentary on Excess and Inequality.

0 Comments