In 1920 the New Republic ran “A Test of the News,” a special supplement to the magazine (published soon after as the book Liberty and the News) by Walter Lippmann and Charles Merz showing that in the three and a half years since the Bolshevik revolution, the New York Times had reported “not what was, but what men wished to see.” On ninety-one occasions, the paper had reported that the new regime was on the verge of collapse, although the only real “censor and . . . propagandist were hope and fear in the minds of reporters and editors” themselves.

Lippmann later claimed to identify something more profoundly problematic than bad reporting: “the very nature of the way the public formed its opinions,” as his biographer Ronald Steele put it. He despaired of a public of citizens with enough time and competence to weigh evidence and decide important questions, and in 1922 he published Public Opinion, which contended that experts needed to be insulated from democratic tempests when making decisions, which could then be ratified by voters. Lippmann’s contemporary John Dewey called it “perhaps the most effective indictment of democracy as currently conceived ever penned.”

| Dean Starkman nails the “access” business press’s incredible failure to chronicle and assess the onrushing train wreck of predatory lending and hyper-financialization. |

Public Opinion has never gone out of print, and it’s still easy to imagine elites at Davos telling one another that while “the people” should be consulted, ultimately they must be ruled. But what if the experts and media watchdogs can barely rule themselves? What if they haven’t kept faith with a public that responds more constructively to reporting and education better than what Lippmann encountered?

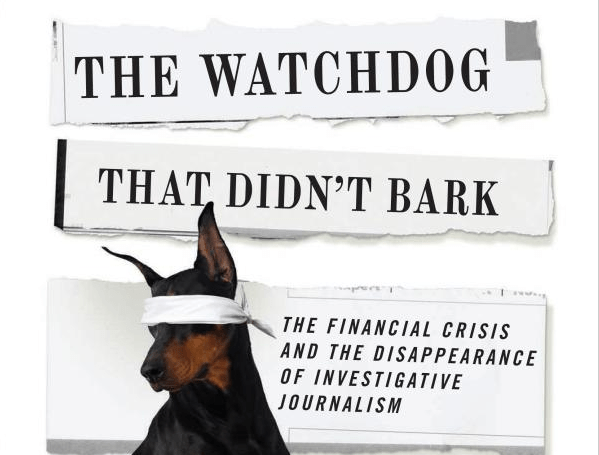

Ninety-two years later, the Columbia Journalism Review has outdone Lippmann’s indictments of both the press and the public—along with Dewey’s democratic response—with an excerpt of the veteran Wall Street Journal and CJR journalist Dean Starkman’s subtle, devastating The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark: The Financial Crisis and the Disappearance of Investigative Journalism. CJR first published the extensive survey that seeded Watchdog, “Power Problem: The Business Press Did Everything But Take on the Institutions that Brought on the Financial Crisis,” three years ago, but the book goes much farther than that.

Unlike Lippmann’s Public Opinion, Starkman’s Watchdog presents no sweeping, grandiloquent indictments of the “omnicompetent” citizen whose mythical, democratic sovereignty Lippmann exploded. Starkman keeps a more realistic faith in both democracy and journalism by drawing two important distinctions.

First, he distinguishes “access” journalism from “accountability” journalism in business reporting. Access journalism, driven almost algorithmically to boost profits (like much of the stock-market), suspends its critical judgment about premises and practices to win insider tips about mergers, acquisitions, and financial gimmicks. “Accountability” journalism is harder, more stressful, and makes enemies. But such investigative reporting can lead to what Starkman calls “the Great Story,” which exposes systemic rights and wrongs, inspires prosecutions, and holds financial drivers and their drones up to the light of public judgment.

Second, Starkman shows that although “accountability reporting tends to help everyone in general, but no one in particular,” journalists and citizens can and do make choices to pursue it out of a public-mindedness that confounds the seemingly irresistible seductions and imperatives of the market. And while accountability journalism has been produced mainly by investigative print reporters paid to take their time and dig deep, Starkman does not defy today’s digital tsunamis. Accountability journalism “is not a medium, like print or TV,” he explains. “It’s not an institution, like The New York Times or the Huffington Post. It’s neither alternative nor mainstream. It’s neither inherently analogue nor digital. It’s a practice.” Indeed, Starkman explains how the supposedly “free for all” internet is being colonized by owners intent on taming and channeling our energies as surely as newspaper owners did in the nineteenth century.

Even under the best of conditions, accountability reporting is a hard practice, not least because access and accountability are yin and yang; journalism needs both. But Watchdog shows business journalists like CNBC’s Jim Cramer abandoning the hard road to be Wall Street “messenger boys” because the material rewards and excitement seem greater. Until they become disastrous. As decisively as Lippmann nailed the Times’ failure to report developments in Russia, Starkman nails the “access” business press’s incredible failure to chronicle and assess the onrushing train wreck of predatory lending and hyper-financialization, whose engineers it actually glorified.

He lets respected business reporters like the Times’s Diana Henriques insist, “The government, the financial industry, and the American consumer—if they had only paid attention—would have gotten ample warning about this crisis from us, years in advance, when there was still time. . . .” But while the mainstream business press did produce some early accounts of how financial deregulation facilitated bad lending, Starkman finds that by 2005 there “was a bubble, all right, and the business press was in it.” He demonstrates scrupulously that “Anyone ‘paying attention’ to the conventional business press could be forgiven for thinking that things were, in the end, basically normal.”

The real heroes of this story are dogged local reporters like Michael Hudson, working at small papers in cities like Roanoke, Virginia and Pittsburgh, who had the temerity and the outsider’s freedom from the temptations of access to discover and analyze what was going on as early as 2004. Reading this, I couldn’t help but think also of John Cichowski and Shawn Boburg at New Jersey’s Bergen Record, who intrepidly cornered Governor Chris Christie’s staff for its partisan “traffic problem” retributions when most “big foot” reporters were vying for front-row seats in Christie’s political theater.

The book is chock-a-block with entertaining anecdotes, some drawn from Starkman’s own years at the Wall Street Journal, and this intimacy with bad actors as well as good ones makes his critique compelling. But what makes Watchdog a truly rare gift, transcending even Lippmann’s, is Starkman’s civic faith, which enables him to distill from his experience some real clarity about journalism and its proper mission: “It’s not enough for reporters and editors to struggle against great odds as many of them have been doing. It’s time to take the public into our confidence. The news about the news needs to be told. . . . Because, in the run-up to the global financial crisis, the professional press let the public down.” He still believes that the media’s mission isn’t to accelerate and ride economic growth but to strengthen the public virtues and institutions that guarantee the press’s own independence.

Jim Sleeper, a writer and teacher on American civic culture and politics and a lecturer in political science at Yale, is the author of The Closest of Strangers: Liberalism and the Politics of Race in New York and Liberal Racism. He is on the editorial board of Dissent, where this originally appeared.

0 Comments