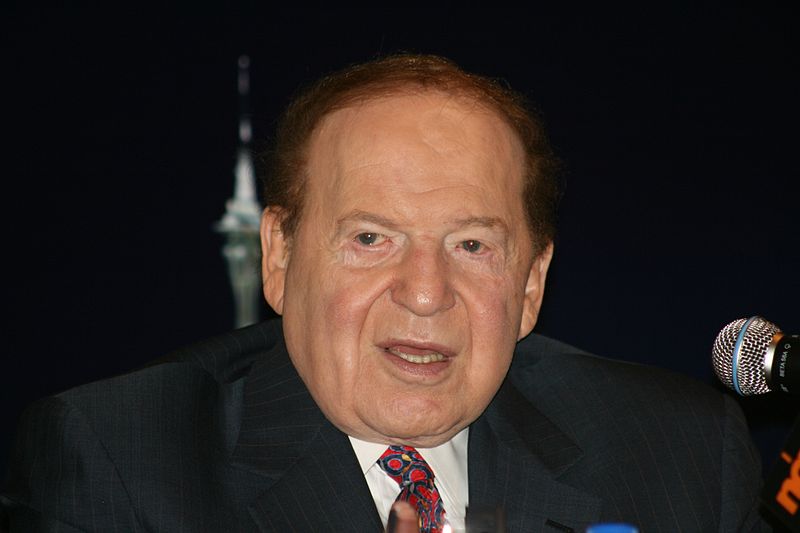

(Sheldon Adelson | Cource: Wikipedia)

Fifty years ago, Americans lived in a society that had been growing—and had become—much more equal. In 1963, of every $100 in personal income, less than $10 went to the nation’s richest 1 percent.

Americans today live in a land much more unequal. The nation’s top 1 percent are taking just under 20 percent of America’s income, double the 1963 level.

But no Americans, in all the years since 1963, have ever voted for doubling the income share of America’s most affluent. No candidates, in all those years, have ever campaigned on a platform that called for enriching the already rich.

Yet the rich have been enriched. America’s top 0.01 percent reported incomes in 1963 that averaged $4.1 million in today’s dollars. In 2011, the most recent year with stats available, our top 0.01 percent averaged $23.7 million, nearly six times more than their counterparts in 1963, after taking inflation into account.

This colossal upward redistribution of income took years to unfold, and—for many of those years—most Americans didn’t even realize that some grand redistribution was even taking place.

Few Americans remain that clueless today. Most of us now have a fairly clear sense that American society has become fundamentally—and dangerously—more unequal. The starkly contrasting fortunes of America’s 1 and 99 percent have become a staple of America’s political discourse.

So why is this stark contrast continuing to get even starker?

Americans do, after all, live amid democratic institutions. Why haven’t the American people, through these institutions, been able to undo the public policies that squeeze the bottom 99 percent and lavishly reward the crew at the top?

Why, in other words, hasn’t democracy slowed rising inequality?

Four political scientists are taking a crack at answering exactly this question in the current issue of the American Economic Association’s Journal of Economic Perspectives, a special issue devoted to debating America’s vast gulf between the rich and everyone else.

| Voters of modest means outnumber voters of excessive means in every election. Yet public policy in America essentially comforts only the already comfortable. |

The four analysts—Stanford’s Adam Bonica, Princeton’s Nolan McCarty, Keith Poole from the University of Georgia, and NYU’s Howard Rosenthal—lay out a nuanced reading of the American political scene that explores the interplay of a wide variety of factors, everything from the impact of the partisan gerrymandering of legislative districts to voter turnout by income level.

But one particular reality dramatically drives their analysis: Societies that let wealth concentrate at enormously intense levels will quite predictably end up with a wealthy who can concentrate enormous resources on getting their way.

These wealthy underwrite political campaigns. They spend fortunes on lobbying. They keep politicians and bureaucrats “friendly” to their interests with a “revolving door” that promises lucrative employment in the private sector.

Bonica, McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal do an especially engaging job exploring, with both data and anecdotal evidence, just how deeply America’s super rich have come to dominate the nation’s election process.

One example from their new paper: Back in 1980, no American gave out more in federal election political contributions than Cecil Haden, the owner of a tugboat company. Haden contributed all of $1.72 million, in today’s dollars, almost six times more than any other political contributor in 1980.

In the 2012 election cycle, by contrast, just one deep-pocket couple alone, gaming industry giant Sheldon Adelson and his wife Miriam, together shelled out $103.4 million to bend politics in their favored wealth-concentrating direction.

The Adelsons sit comfortably within the richest 0.01 percent of America’s voting-age population. Over 40 percent of the contributions to American political campaigns are now emanating from this super-rich elite strata.

In the 1980s, campaign contributions from the top 0.01 percent roughly equaled the campaign contributions from all of organized labor. In 2012, note Bonica, McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal in their new analysis, America’s top 0.01 percent all by themselves “outspent labor by more than a 4:1 margin.”

Donors in this top 0.01 percent, their analysis adds, “give pretty evenly to Democrats and Republicans”—and they get a pretty good return on their investment. Both “Democrats as well as Republicans,” the four analysts observe, have come to “rely on big donors.”

What has this reliance produced? Nothing good for average Americans. Back in the 1930s, Democrats championed the financial industry regulations that helped create a more equal mid-20th century America. In our time, Democrats have helped undo these regulations.

In 1993, a large cohort of Democrats in Congress backed the legislation that ended restrictions on interstate banking. In 1999, Democrats helped pass the bill that let federally insured commercial banks make speculative investments.

The next year, a block of congressional Democrats blessed a measure that prevented the regulation of “derivatives,” the exotic new financial bets that would go on to wreak economic havoc in 2008.

We’ll never be able to fully “gauge the effect of the Democrats’ reliance on contributions from the wealthy,” acknowledge political scientists Bonica, McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal. But at the least, they continue, this reliance “does likely preclude a strong focus on redistributive policies” that would in any significant way discomfort the movers and shakers who top America’s moneyed class.

Conventional economists, the four analysts add, tend to ascribe rising inequality to broad trends like globalization and technological change—and ignore the political decisions that determine how these trends play out in real life.

New technologies, for instance, don’t automatically have to concentrate wealth — and these new technologies wouldn’t have that impact if intellectual property laws, a product of political give-and-take, better protected the public interest.

But too many lawmakers and other elected leaders can’t see that “public interest.” Cascades of cash—from America’s super rich—have them conveniently blinded.

Sam Pizzigati is an Associate Fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies and editor of Too Much: A Commentary on Excess and Inequality.

This article originally appeared in Too Much.

0 Comments