Photo Credit: Derzsi Elekes Andor

I’ve been studying the history of American conservatism full time since 1997—almost 20 years now. I’ve read almost every major book on the subject. I thought I knew what I was talking about. Then along comes Donald Trump to scramble the whole goddamned script.

Now, historians must begin to consider alternate genealogies of the American right: lineages for the orange-haired monster that no one saw coming. Our received narrative of the movement encompassed by Barry Goldwater and William F. Buckley and Strom Thurmond and Milton Friedman and Ronald Reagan just doesn’t cut it any longer. I’ve done my best to begin the work—thinking through, for instance, Trumpism’s connection to fascism, a political tradition not heretofore considered all that relevant in the American context. Other bodies, however, are buried closer to home.

No history of modern conservatism I’m aware of finds much significance in the 22,000 Nazi sympathizers who rallied for Hitler at Madison Square Garden in February 1939, presided over by a giant banner of General George Washington that stretched almost all the way to the second deck, capped off by a menacing eagle insignia. Nor the now-infamous Ku Klux Klan march through the streets of Queens in 1927, when The New York Times reported “1,000 Klansmen and 100 policemen staged a free-for-all,” in which according to one contemporary news report all the individuals arrested were wearing Klan attire, and that one of those arrestees was Donald Trump’s own father.

In the specter of the son’s likely ascension as Republican nominee, however, such events gather significance. Consider the subsequent history of Fred Trump’s career as a developer of middle-class housing in the outer boroughs of New York City. We now know Fred Trump was notorious enough a racist to draw the attention of Woody Guthrie, who wrote a song about him in the 1950s: “I suppose/ Old Man Trump knows/ Just how much/ Racial Hate/ he stirred up/ In the bloodpot of human hearts/ When he drawed/ That color line/ Here at his/ Eighteen hundred family project.”

Twenty years later—by which time he had brought his son in as his apprentice—the hate Old Man Trump stirred in the bloodpot of human hearts became a matter of legal record, when the United States Justice Department sued Trump père et fils for violating the Fair Housing Act of 1968 in operating 39 buildings they owned. Testifying in his own defense, young Donald (who would soon be seen around town in a chauffeured limousine with a license plate reading “DJT”), testified that he was “unfamiliar” with the landmark law. As the evidence in the federal case against the Trump organization became close to incontrovertible, he told the press the suit was a conspiracy to force them “to rent to welfare recipients,” a form of “reverse discrimination.” This proud and open refusal to rent to welfare recipients—whom he said contribute to “the detriment of tenants who have, for many years, lived in these buildings, raised families in them, and who plan to live there”—was Donald Trump’s defense against racism.

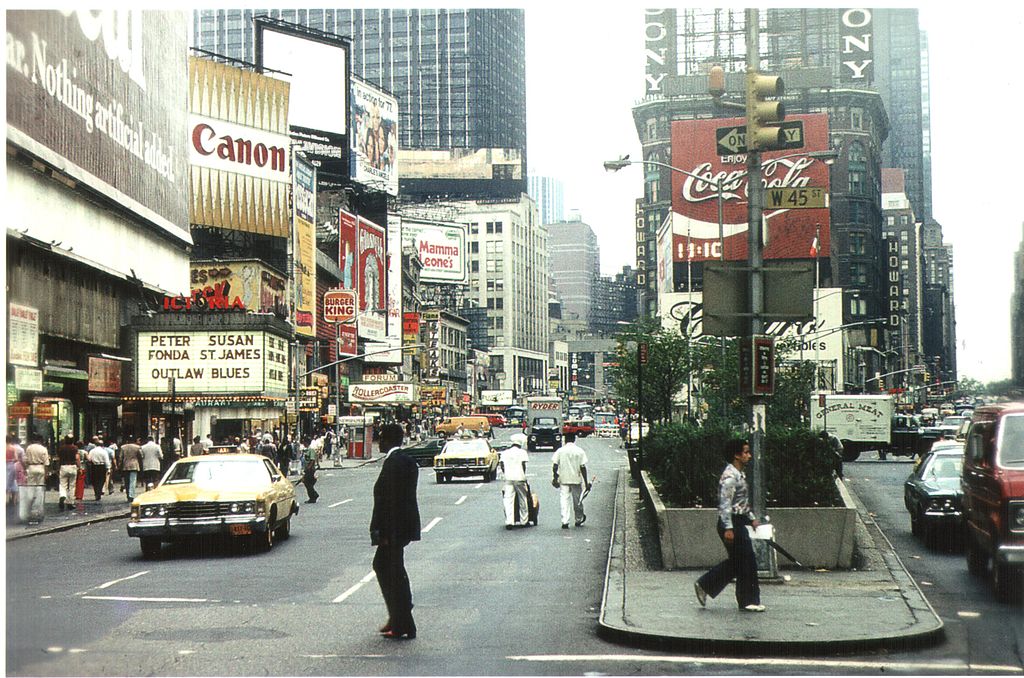

It is in this saga that we locate the formation of Donald Trump’s mature political vision of the world, in continuity with America’s racist and nativist heyday of the 1920s, and within the context of a cultural world much more familiar to us: New York in the 1970s, that raging cauldron of skyrocketing violent crime, subway trains slathered with graffiti, and a fiscal crisis so dire that even police were laid off in mass—then the laid off cops blocked the Brooklyn Bridge, deflating car tires, and yanking keys from car ignitions.

Think of Trump coming of age in the New York of the 1977 blackout, the search for the Son of Sam, and Howard Cosell barking out “Ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning” during game two of the World Series at Yankee stadium as a helicopter hovered over a five-alarm fire at an abandoned elementary school (40 percent of buildings in the Bronx were destroyed by the end of the 1970s, mostly via arson—often torched by landlords seeking insurance windfalls).

Think of Trump learning about the ins and outs of public life in this New York, a city of a frightened white outer-borough middle-class poised between fight or flight, in which real estate was everywhere and always a battleground, when the politics of race and crime bore all the intensity of civil war.

In The Invisible Bridge I wrote about what it was like in this New York in 1974, the summer when the federal lawsuit against the Trumps was approaching its climax, the summer when a controversial new movie began packing theaters across the five boroughs.

Death Wish starred a then-obscure Charles Bronson as a New York City architect who used to be liberal, until his daughter was raped and his wife murdered. His son-in-law pronounces defeat: “There’s nothing we can do to stop it. Nothing but cut and run.” The architect, by contrast, learns to shoot a gun—in an Old West ghost town—so he can start mowing down muggers at point-blank range. He soon cuts the city’s murder rate in half, and wins a spot on the cover of Time.

Liberal reviewers registered their disgust: The Times’s Vincent Canby called it “a bird-brained movie to cheer the hearts of the far-right wing,” then, 10 days later, branded Bronson a “circus bear.” Time called it “meretricious,” “brazen,” and “hysterical.” Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times labeled it “fascist.” But in the real-life New York City, where the murder rate had doubled in 10 years, and where a psychiatrist published a Times op-ed bragging about the violence he had prevented by leveling a pistol that he kept “never far from my reach while I attend to patients in my mid-Manhattan office,” each onscreen vigilante act won ovations from grateful fans—sometimes standing ovations.

Two years later came an even darker, and considerably more critical, portrait of New York City’s escalating culture of vigilantism. In Taxi Driver, a deranged Vietnam veteran speaks what must have been the unspoken inner monologue of any number of real-life New Yorkers who felt trapped in an urban sewer: “Someday a real rain will come and wash all this scum off the streets.” Pistol in hand, he rehearses his revenge in the mirror: “Listen, you fuckers, you screwheads. Here is a man who would not take it any more. A man who stood up against the scum, the cunts, the dogs, the filth, the shit. Here is a man who stood up.”

When, around that time, Wall Street Journal columnist Irving Kristol coined the phrase “a neoconservative is a liberal who’s been mugged by reality”—a bowdlerization of the older adage “a conservative is a liberal who’s been mugged”—he probably didn’t have Charles Bronson in mind, let alone taxi driver Travis Bickle. Nonetheless the politics is all of a piece. Charles Bronson conservatism, Travis Bickle conservatism, the conservatism of avenging angels protecting white innocence in a “liberal” metropolis gone mad: this is New York City’s unique contribution to the history of conservatism in America, an ideological tradition heretofore unrecognized in the historical literature. But without it, we cannot understand the rise of Donald Trump.

Trump’s political debut, after all, came in response to a mugging. Following the infamous attack on a female jogger in Central Park, Trump purchased full pages in four New York newspapers demanding, “Bring Back the Death Penalty. Bring Back Our Police!” All the hallmarks of his present crusade against “political correctness” were in evidence, such as the harkening to that bygone day when men were men, cops were cops, and punks were punks. He concluded: “I miss the feeling of security New York’s finest once gave the citizens of this City.” As I previously reported, these same police straight-jacketed by liberal timorousness had already coerced the rape suspects into confessions later proven to be false.

That’s N.Y.C.’s avenging-angel conservatism in a nutshell. And now that Trump is gliding toward an expected landslide in the New York primary on Tuesday, April 19, we must begin the work of excavating its history.

We might start with William F. Buckley—though other scholars can surely date it back further. The National Review editor’s quixotic campaign for New York mayor in 1965 is best remembered for a self-effacing quip. (“What will you do if you win?” he was asked. “Demand a recount.”) Buckley himself is now celebrated as the genteel warrior of the conservatism of a more civilized age: The New York Times, upon his death in 2008, averred of that 1965 race, “He injected a rare degree of lofty oratory into city politics.”

Think of Trump coming of age in the New York of the 1977 blackout, the search for the Son of Sam, and Howard Cosell barking out “Ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning.”

What he also injected was an unprecedented reactionary thuggishness. Like his idea to “undertake to quarantine all addicts, even as smallpox carriers would be quarantined during a plague.” Or “relocating chronic welfare cases outside the city limits”—in what his critics described as concentration camps for the poor. The campaign might have begun as a lark. He received hardly more than 10 percent of the vote. But in a harbinger of things to come, he finished second in some Catholic neighborhoods in Queens. Cops wore “Buckley For Mayor” buttons. When the election’s winner, the very liberal John Lindsay, campaigned in those same neighborhoods, young white men waved “Support your Local Police” placards in his face.

The stage was set, in 1966, for the next New York City law-and-order melodrama. Lindsay, now mayor, fulfilled a campaign pledge by establishing a Civilian Complaint Review Board to protect citizens from abusive cops, the better to restore trust in a police force whose utter rot was the subject that year of a bestselling book about a cop named Frank Serpico, whose reward for refusing to break the law was an attempt by fellow cops on his life.

The president of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association responded to Mayor Lindsay’s new board: “I am sick and tired of giving in to minority groups and their gripes and their shouting.” After a Brooklyn riot in which cops had been ordered not to use their nightsticks, the PBA got 96,888 signatures to put a referendum on the November ballot to dissolve the review board (they only needed 25,000). Their TV commercials brayed, Trump-like, Bronson-like, “The addict, the criminal, the hoodlum: only the policeman stands between you and him.” Buckley—who had orated on the campaign trail, “We need a much larger police force, enjoined to lust after the apprehension of criminals,” unencumbered by “any such political irons as civilian review boards”—might only have received 10 percent of the vote. But 12 months later, the anti-CCRB referendum won 63 percent of the popular vote. Even Jews, who were supposed to be liberal, opposed it 55 percent to 40 percent.

Two years later, George Wallace brought his independent presidential bid to Madison Square Garden. “We need some meanness,” Wallace brayed. And he got it: police had to rescue black protesters from a mob that surrounded them and chanted, “Kill ‘em!” The New Republic observed, “Never again will you read about Berlin in the ’30s without remembering this wild confrontation of two irrational forces.”

The confrontation is the key: one of the things that makes New York’s conservatism of avenging angels so feral is its proximity to so many damned left-wingers. Left-wingers like Mayor Lindsay—who only won reelection in 1969 because the white ethnic backlash vote was split between two candidates, one of whom, Mario Procaccino, helped popularize the phrase “limousine liberal” in describing Lindsay.

In 1971, Lindsay elected to build publicly subsidized housing in the Queens neighborhood of Forest Hills, partly upon the presumption that its largely Jewish population, only two and half decades on from the Holocaust, would be relatively free from racism of the Fred Trump sort. Apparently hizzoner wasn’t paying attention to the growing following behind Rabbi Meir Kahane, the domestic terrorist who was another of New York City’s sui generis contributions to the history of the American right.

Village Voice columnist Jack Newfield reported from one of the mayor’s damage-control sessions at the Forest Hills Jewish Community Center, where Jews called “Lindsay redneck names under the shadow of the Torah.” The Voice’s Paul Cowan heard a picketer boast, “If Lindsay ever gets to be president, I’ll kill him. I’ll do just what Oswald did to John Kennedy.” His companion replied, “You won’t get the chance. Lindsay is going to get shot right here in New York.”

Donald Trump, 25 years old, was just then beginning his apprenticeship in his father’s real estate organization.

He made the acquaintance of Roy Cohn, who represented the family against the federal racial bias lawsuit, devising the defense that Fred Trump had no intention of excluding black tenants, just welfare recipients. Trump became a student of the legendarily reptilian thug who came to prominence as Joseph McCarthy’s lawyer. Long-time Trump-watcher Michael D’Antonio has explained: “Both were members of Le Club, a private hot spot where the rich and famous and social climbers could meet without suffering the presence of ordinary people.” Writes D’Antonio, “Cohn modeled a style for Trump that was one part friendly gossip and one part menace. . . . Trump kept a photo of the glowering Cohn so he could show it to those who might be chilled by the idea that this man was his lawyer.”

It was Cohn, indeed, who introduced Trump to the nearly-as-reptilian Roger Stone, the professional dirty trickster and sexual adventurer with the giant tattoo of Richard Nixon on his back—and who, even though Trump has called him a “stone-cold loser,” has managed to hang on to a position of influence in the Trump presidential campaign. He certainly maintains an influence on Donald Trump’s view of the world. “When somebody screws you,” Stone told a reporter, “Screw ’em back—but a lot harder.” Figures like Cohn and Stone represent another branch in the New York conservative tradition: flashy, hedonistic right-wing operatives who gargle with razor blades and wear their shiny silver three-piece suits like armor.

Next comes an avenging angel named Ed Koch.

A former liberal, Koch won his underdog mayoral victory in 1977 in a madcap electoral free-for-all whose tenor was set on the night of July 13, when a series of lightning strikes shut down transmissions lines, the city shuddered to black, and so much crime ensued that buses filled with men in chains shuttled from jailhouse to jailhouse in search of available cells.

Neoconservative Midge Decter wrote in Commentary that it was like “having been given a sudden glimpse into the foundations of one’s house and seen, with horror, that it was utterly infested and rotting away.” The supposedly liberal readership of The New York Times wrote letters to the editor like this one: “The Puerto Ricans can go back to Puerto Rico. They belong there anyway, and if the blacks do not shape up they can go to the South.”

Ed Koch was virtually unknown outside his Greenwich Village neighborhood, but with a pledge to restore the death penalty, his campaign took off like a rocket. Never mind that the New York mayor had no power over capital punishment. The people had spoken: a mere 25 percent opposed bringing back what New York Daily News called “little hot squat.”

Meanwhile Koch berated the “poverty pimps” and “povertitians” holding a broke city hostage, demanded the abolition of the Board of Education (a “lard barrel of waste”), denounced alleged welfare fraud, decried “the nuts on the left who dump on middle class values.” He promised, too, to unwind New York’s experiments with free college, generous welfare, and subsidized housing, which its cheerleaders on the left called “socialism in one city.”

One of those cheerleaders was the one-time front-runner in the race, the very liberal Congresswoman Bella Abzug. After the blackout riots, her campaign went into a tailspin; she didn’t even make it into the runoff.

An underdog did instead: the young Mario Cuomo. He said, “the death penalty cannot provide jobs for the poor. The electric chair cannot balance the budget. The electric chair cannot educate our children. The electric chair cannot give us a sound economy or save us from bankruptcy or even save my seventy-seven-year-old mother.” And besides, he would add, America was better than that. Or was it? One time when he tried to make that same point, an old lady in Brooklyn spat in his face. Another time, someone stood up and cried, “Kill them!”

Koch won, of course, and then served as New York’s mayor for the next dozen years. Although to outer-borough reactionaries like state Senator Chris Mega of Brooklyn, he was just another liberal sellout on gun control. At a December 1984 press conference, Mega demanded to know: “When will Mayor Koch provide the same level of protection to the citizens who ride the subways and pay their taxes that he enjoys surrounded by a phalanx of New York’s finest, guns at the ready?”

That particular press conference was called by the National Rifle Association in support of Bernhard Goetz, an electronics salesman from Kew Gardens, Queens, who shot five young men on a graffiti-encrusted subway car who, depending on whom you believed, were either preparing to mug him or aggressively panhandling for $5. Like the character played by Charles Bronson, Goetz made the cover of Time magazine. Celebratory bumper stickers bloomed: “Ride With Bernie—He Goetz Them.” In a later interview he reflected, Travis Bickle-like, “The guys I shot represented the failure of society. . . . Forget about their ever making a positive contribution to society. It’s only a question of how much a price they’re going to cost. The solution is their mothers should have had an abortion.”

One of Goetz’s biggest backers was Bob Grant, who beginning on WMCA in 1970, and then on WOR (until he was fired in 1979 for saying the only reason a black woman got her job was that “she passed the gynecological and pigmentation test”), virtually invented right-wing talk radio—and when you think about it, it hardly could have been invented anywhere else but New York. Grant won the first live radio interview with Goetz, in 1986, lamenting that he had not “finished the job by killing them all.”

Three years later, after the assault in Central Park, Donald Trump offered his memorable argument to bring back little hot squat. “What has happened is the complete breakdown of life as we know it. . . . How can our great society tolerate the continued brutalization of its citizens by crazed misfits? Criminals must be told that their CIVIL LIBERTIES END WHEN AN ATTACK ON OUR SAFETY BEGINS.”

In 2011, Bob Grant, impressed with Donald Trump’s campaign to force President Obama to produce his birth certificate, announced he had found his presidential candidate for 2012. Grant died in 2014, but two years later, his brand of vigilante conservatism has gone fully national. The wall Fred Trump sought to build in Queens in the early 1970s has been relocated 2,000 miles south. On Tuesday, Donald Trump will win a landslide in his home state. And somewhere, Bob Grant will be smiling.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks