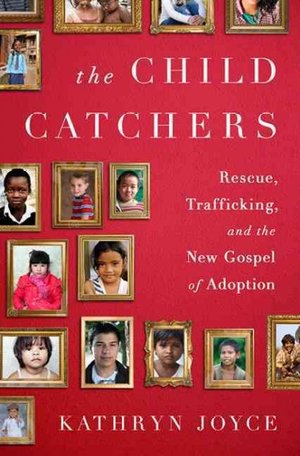

The Child Catchers: Rescue, Trafficking and the New Gospel of Adoption, by journalist Kathryn Joyce, forces readers to question just whose needs are satisfied by adoption, driven as it is now by conservative Christians and a dangerous desire to do good.

Joyce unpacks a multibillion-dollar transnational industry that is manufacturing orphans to satisfy the demands of an evangelizing mission.

As Pierre Alexis, the director of the Maison Des Enfants orphanage in Port-au-Prince, tells Joyce, “I know [God] likes it when we are feeding them, but He likes better—He loves—when the children are growing as His servants.”

Such sentiments, expressed by many adoptive parents and adoption intermediaries interviewed for the book, betray a priority for saving souls over lives.

It is this agenda that is having horrific consequences for families in Guatemala, Ethiopia, Liberia, Haiti and the U.S., while blinding policymakers to alternatives to intercountry adoption.

In Christian adoption, each child generates fees of around $20,000 to $35,000—sometimes as high as $60,000.

Take, for instance, the experience of Tarikuwa.

At age 13, the Ethiopian teenager was adopted by Katie and Calvin Bradshaw in New Mexico, who believed she was seven and close in age to their biological children.

The Bradshaws were also told Tarikuwa’s mother had died of AIDS and her father was HIV positive and warned that unless she and her two younger sisters were adopted “a life of prostitution is all but assured.”

Tarikuwa’s biological father was in fact a healthy government worker earning middle-class Ethiopian wages. Adoption, as he understood it from a presentation he attended at his local church, was more like a foreign exchange program, a chance for Tarikuwa and her younger sisters to be educated in the U.S. No one warned him that adoption was forever.

By the time Tarikuwa found out, the paperwork was done. Katie Bradshaw witnessed the child fall into a grief so painful she was unsure whether the child would survive. In hindsight, Bradshaw, who mortgaged her house to adopt, says she had fallen prey to “faith manipulation.” The church had cultivated a need to be a savior and promoted adoption as a means to fulfill it.

In another case, Tennessee mother Jessie Hawkins was shocked when the four-year-old Ethiopian girl she and her husband adopted learned enough English to explain that she had another mom.

“I can’t even begin to put into words what that feels like,” Hawkins tells Joyce. “Finding out that you have someone else’s child simply because you happen to have been born in a country where you’re more privileged than they are? You want to throw up, you don’t know what to do.”

These may seem like extreme consequences of a savior complex that in a more benign form might yield happy results. But the failure to ask who benefits from well-intentioned deeds is morally inept.

Consider “voluntourism,” short vacations promoted by churches as a way to combine missionary work and sightseeing. On its face, a project to volunteer in an orphanage is mutually beneficial. However, the personal enrichment of the volunteer, paying thousands for the experience, often trumps the emotional needs of the orphan. The orphan who forms an intense bond can be left with fresh feelings of abandonment after the charity and voyeurism are done.

Consider “voluntourism,” short vacations promoted by churches as a way to combine missionary work and sightseeing. On its face, a project to volunteer in an orphanage is mutually beneficial. However, the personal enrichment of the volunteer, paying thousands for the experience, often trumps the emotional needs of the orphan. The orphan who forms an intense bond can be left with fresh feelings of abandonment after the charity and voyeurism are done.

The fetishization of poverty chronicled in The Child Catchers is not new. One only needs to recall the tourists taking buses through New Orleans’ Ninth Ward after Hurricane Katrina to know its other forms. A short history of New York will also show that “slumming” in the depravity of the Bowery was a popular middle-class pursuit at the end of the 19th century.

What is frightening about adoptive parents’ boasts today of having “beautifully filthy” children or a child so poor that “we, by contrast, have all the power in the world” is the willingness with which these parents exploit the disparity to reinforce their own magnanimity. Stepping into the role of savior, of course, disregards the burden of being cast as saved.

In Christian adoption, says Joyce, each child generates adoption fees of around $20,000 to $35,000—sometimes as high as $60,000. In Haiti, the fees paid by adoptive parents in the U.S. and Europe range from $10,000 to $25,000. This is in a country where about 80 percent of the population lives on $2 a day.

Why then is intercountry adoption favored over sustainable development, disaster relief and in-country care?

Perhaps the urgency associated with rescue and the vulnerability of children contributes to the tunnel vision. Perhaps there is a latent imperialism causing mothers of the West to think they know best how to raise a child. Perhaps it’s a combination of all of these forces working together and too many people profiting from the misery.

Yuko Narushima is a journalist living in New York. Her investigative report on the trafficking of women in foreign embassies in the U.S. appeared in the March issue of the Spectator.

0 Comments