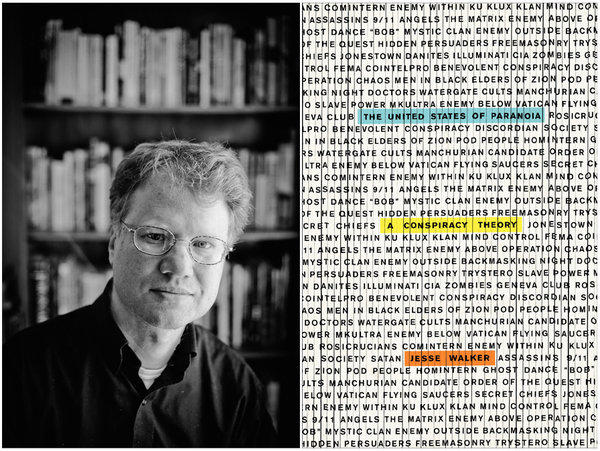

The United States of Paranoia is witty, smart, and more than a little subversive. Ranging confidently through history and popular culture—from the Indian wars of Puritan New England to Andrew Jackson assassination conspiracy theory and the deconstructive tricksters behind Discordianism’s Operation Mindfuck, from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown” to Jack Chick’s Evangelicalist comic books—Jesse Walker shows that conspiracism is far from just a foible of the fringe.

“When I say virtually everyone is capable of paranoid thinking,” he declares, “I really do mean virtually everyone, including you, me, and the founding fathers.” The managing editor of the libertarian magazine Reason, Walker is a far cry from a Birther or a New World Order fanatic of the Alex Jones persuasion. But he doesn’t grant much deference to the two-party establishment either.

Conspiracists are primed to believe that the government lies to them because it so manifestly does.

And why would he? It’s a little rich to think that the Warren Commission relied upon “objective” investigations conducted by the CIA and the FBI: these agencies were the architects of such paranoia-inducing programs as MKUltra, which tested LSD on unwitting civilians, and COINTELPRO, which planted provocateurs and double agents in far left- and right-wing organizations throughout the 1950s and 1960s. As irrational as the 9/11 Truth movement might be, the bipartisan panic that inflated Al Qaeda into a global superpower, giving rise to the PATRIOT Act, with its secret searches and warrantless internet surveillance, not to mention the foreign quagmires that killed thousands of American soldiers and hundreds of thousands of Afghani and Iraqi civilians, had consequences that were far worse.

Walker’s larger point is one that historian Kathryn Olmsted makes in Real Enemies: Conspiracy Theories and American Democracy, a volume that Walker refers to and quotes from. Government officials have long “promoted a certain conspiracist style,” Olmsted writes, “but they wanted to maintain the power to construct these conspiracy theories themselves and quash those that did not serve official interests.” Whether the topic is Pearl Harbor, Building Number 7, or Area 51, conspiracists are primed to believe that the government lies to them because it so manifestly does.

Walker is no racist and he is too much of an ironist to make use of Ron Paul tropes like “treason” and “tyranny.” But he is quick to defend racists and militias when they are, as he sees it, unfairly demonized. He tellingly contrasts the influence that John Todd—who claimed to be a defector from the Satanic Illuminati and enjoyed a brief celebrity in the 1970s—had on Kerry Noble, a founder of the racist paramilitary group the Covenant, the Sword, and the Arm of the Lord, and on Randy and Vicki Weaver. Noble, whose CSA targeted Jews, blacks and gays, was imprisoned on federal weapons charges in the mid-1980s. The Weaver family won a $3.1 million settlement from the federal government after a marshal killed Randy Weaver’s son and FBI snipers wounded him and killed his wife at their home in Ruby Ridge, Idaho, in 1992.

“If the story of the CSA shows how a marginal group’s paranoia about the government can drive it to violence,” he writes, “the tale of the Weavers shows how the government’s paranoia about marginal groups can drive it to violence.” During the siege at Waco a year later, Walker writes, the media and the government spread the “same sorts of fables” about the Davidians “that the medieval authorities told about Jews and heretics.”

For Walker, The United States of Paranoia is the antidote to Richard Hofstadter’s 1964 essay “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” which betrayed the same paranoia about the far right, he says, that it accused the far right of having about everyone else. And yet Walker has a gigantic blind spot of his own.

For writers like Hofstadter and myself, it is not simply that the far right is paranoid or deluded or dishonest, or that it suffers from epistemic closure—the closed-mindedness that precludes thought, distorts reality, and often leads to extremist fantasy. The specific contents of extreme conservative beliefs matter too, as do the objects of their paranoia.

Governments lie to acquire, exploit, and keep power; to that extent conspiracism is an important part of any politician’s propagandistic toolkit. But at a certain bedrock level, the paranoid style that Hofstadter wrote about—the “overheated, oversuspicious, overaggressive, grandiose, and apocalyptic” conviction that a secret adversary has wormed its way into the heart of the establishment—becomes a kind of theology and one that turns on an absolute idea about the way things are—and on the immutable nature of the supposed enemy.

The ubiquity of The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion in conspiracist circles is a matter of unconcern to Walker. Trying to link together all the groups that believe in it, he says, resembles “Woody Allen’s syllogism ‘Socrates is a man. All men are mortal. Therefore, all men are Socrates.’” I couldn’t disagree more.

As flawed as it is, the American experiment is premised on Enlightenment humanism. The paranoid conspiracism described by Hofstadter and epitomized by the Protocols, in contrast, proposes that some among us, whether Jewish bankers or heirs to ancient astronauts, owe their ultimate allegiance to Satan.

That these conspiracists have remained as influential as they have is something to be paranoid about.

Arthur Goldwag’s most recent book is The New Hate: A History of Fear and Loathing on the Populist Right. You can follow him on Twitter at @ArthurGoldwag.

0 Comments