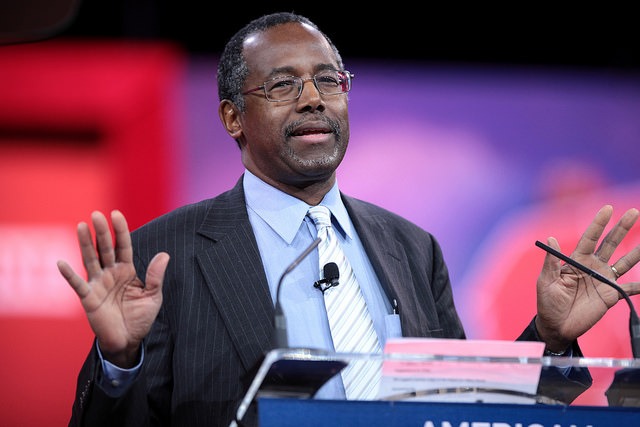

Photo Credit: Gage Skidmore

Ben Carson was on the ropes at the last Republican debate. But it didn’t matter. By that time, his improbable run for the presidency was all but over.

In fact, the campaign was already on life support the last week in December, when campaign manager Barry Bennett was sent packing, along with the communications director and support staff. Bennett, a peripatetic consultant and Capitol Hill staffer, is best known for a scathingly effective 2012 attack video targeting Mitt Romney, paid for by a political action committee supporting Newt Gingrich.

Before Bennett boxed up his files, packed up his laptop, and moved over to the Trump campaign office, he phoned in his post-mortem to NBC. “We all know the root of our problems,” he said, “let’s not pretend it’s not Armstrong Williams.”

Bennett is not alone in that view. “All they have to do now is decide who will write the eulogy,” a former Carson campaign adviser told me. “Dr. Carson is out of the race and everyone in the campaign knows it. Armstrong Williams should write the eulogy.”

Williams is a South Carolina businessman who has been involved in Republican Party politics since working as an aide for South Carolina Republican Senator Strom Thurmond, then signing on with Ronald Reagan’s Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Chairman Clarence Thomas. Williams was also an all-in supporter of Thomas’s nomination to the Supreme Court.

Today, Williams is best known as a conservative African-American radio personality and columnist. He also manages Carson’s business affairs.

“Armstrong created Dr. Carson’s candidacy,” the former campaign adviser I spoke to told me. “And Armstrong killed it.”

According to the source, who requested his name be withheld, Williams ran the campaign, driving him away, along with Bill Millis, a South Carolina multi-millionaire who had raised $400,000 for Carson. “Armstrong ran everything,” he said.

To all but the true believers, it’s been obvious for a long time that Carson would never be president of the United States, or even the party’s 2016 nominee.

But the campaign was all about true believers, a handful of them, with money, connections, and an unshakable belief that they could turn a neurosurgeon with a compelling personal narrative and a cult following on the motivational-speaker circuit into a serious presidential candidate.

They came together two and a half years ago, when Carson addressed the National Prayer Breakfast in May 2013. Standing at a lectern four feet from Barack and Michelle Obama, he derided the president’s health care legislation, deficit spending, and tax policy. Health care reform was simple, he explained; everyone would be assigned a health-savings account at birth. To replace the income tax, he suggested something like a national tithe based on the “fairest individual in the universe: God.” As a grace note, he did a riff on the president’s profession: government is unworkable because of lawyers who are taught “to win by hook or by crook.”

The editorial page of The Wall Street Journal declared him a contender. More important, a few wealthy individuals decided that a black man lecturing Obama on a national stage could be funded, groomed, and coached into the Republican Party’s 2016 candidate for president.

The campaign was a Pygmalion story that ended badly.

When the coterie of wealthy supporters who made Carson a candidate, including the Houston lawyer who helped organize an exploratory committee and became the first campaign chairman, were shut out of the campaign, it was over.

Before Carson’s core supporters walked, former campaign chairman Terry Giles told me, the campaign had become a cash cow for consultants.

Giles was as unlikely a chair for a national political campaign as Carson was a candidate for the presidency. He was a criminal defense lawyer in California who had moved on to a civil law practice, car dealerships, a magic club, a chateau-hotel on France’s Cote D’Azur, and a luxury hotel in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. Along the way, he represented comedian Richard Pryor, was the lawyer for a schoolteacher who claimed to have had an affair with Monica Lewinsky, and in Houston, a trustee disposing of Ken Lay’s assets after Enron’s collapse. In a weird way, perhaps he was the perfect man to organize a campaign for Ben Carson, whom Giles had met 20 years earlier when both were inducted into the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans.

It’s a safe bet that Carson will write a book about his improbable run for the presidency. But the better book to come out of the campaign is the Giles playbook.

Giles studied the organizational charts of modern presidential campaigns and came to one important conclusion. “The candidate needs to be surrounded by a small group of trusted advisers, lawyers, business people, who can control what I call the pols, the professional class of political consultants,” Giles said in a phone interview.

He was convinced that consultants had destroyed the McCain and Romney campaigns.

“I knew we had to have a combination of politicos, the cycle-to-cycle pros who move from one campaign to another, and non-political personnel, who safeguard that the politicos wouldn’t take over and do the things they always do: abuse the money on mailers, phone deals, and ad buys that provide them kickbacks; kill research policy; not allow the candidate time to prepare,” Giles said.

“Eighty percent of what the pols do is essential. The other 20 percent can ruin a campaign.”

Starting in the spring of 2014, Giles staffed up the campaign. He scoured conservative think tanks for policy experts to write position papers, which he planned to release over the summer, and to educate the candidate on issues a president would have to master—including foreign policy.

Foreign policy was a challenge. As a candidate, Carson “forgot” the Baltic states are NATO members, missed the founding date of Islam by roughly a millennium, and warned that Shia and Sunni Arabs would unite in a campaign against the United States—all in one disastrous radio interview with a conservative host friendly to his candidacy.

After Giles assembled a campaign staff—which included a “director of campaign culture” to oversee integrity—he moved to the Carson super PAC. The move was, a source for this story told me, “part of a plan backed by Armstrong, to get Terry out of the way.”

Giles was scheduled to return to the campaign last October, after a “cooling-off period” that federal campaign-finance law requires before moving from a PAC to a campaign.

By that time, Giles said, the campaign was a lost cause. “Forty-five days after I had left, the politicos took control,” Giles told me. “What these guys had been doing since mid-June and July were all the wrong things. They eliminated all the policy people, didn’t give Ben time to get prepared.”

“When I finally left, they all raised their own salaries.”

Campaign e-mails provided to The Washington Spectator describe what was lost when Giles walked: speechwriters, media coaches who would teach Carson to read a teleprompter, policy experts who would prep the candidate for debates. (The loss of policy experts was evident, even if unreported. A New York Times article written by a PolitiFact fact-checker reported that 84 percent of the Carson statements scrutinized by PolitiFact were “false or mostly false.”)

Someone in the campaign made sure Giles was gone for good. Leaks to Bloomberg News described his limited grasp of Federal Election Commission rules and implied he was lying about preparing Carson for the October 28 candidates’ debate. Other media outlets cited unnamed sources claiming that Giles’s wife was speaking out at staff meetings about her opposition to Carson’s position on same-sex marriage.

“It was all, excuse me, but it was all bullshit,” Giles said.

Giles said he was never “boxed out” as Bloomberg News reported; he made the decision because for “450 days” he had done all he could while accepting no salary. Carson was no longer listening to his advice.

E-mails obtained by The Washington Spectator indicate that Williams wanted Giles out because Giles couldn’t be controlled. In a telephone interview, Williams said his role in the campaign is exaggerated; he had nothing to do with day-to-day operations, and nothing to do with Giles’s exit.

“I’m Dr. Carson’s confidant, his trusted confidant, I manage his money, the money for his kids,” Williams said. “I do manage the press for the campaign, requests for interviews. But I’m often as surprised as anyone by the news coming out of the campaign.” He added that he and Giles have had joint business interests, including the hotel in Puerto Vallarta.

“Terry has said this to Dr. Carson, and he said it to me,” Williams said. “It was so devastating for him to believe that what he put in place was lost. Terry was willing to point fingers.”

“I don’t have an unkind word to say about anyone,” Williams added.

Granted, it was an unlikely candidacy from the beginning and few pundits and political journalists ever considered Carson anything more than the longest of long shots, if not a vanity candidate.

But perhaps the Giles playbook would have kept Carson in the running through the early caucuses and primaries.

“When I left the campaign in May, it was in good shape,” Giles said. “When I was returning [from the SuperPac] in October, Ben was leading in the polls.”

“I’ve been out since October 25, and I can’t tell you the pain I feel knowing that Ben Carson could have been president.”

When I spoke to Giles last week, he was headed for his home in Puerto Vallarta. Carson was headed for Iowa, polling at 8.5 percent according to the Real Clear Politics eight-poll average—a declivitous fall from his 29.5 percent lead in November.

What does he have to do to stay in the race? I asked Armstrong Williams. “He must finish first or second in Iowa,” Williams said.

“Miracles can happen.”

Carson’s campaign is imperative to heal and inject the true need of our country – to get back to God. A country founded on God’s Word that does not reconcile with its creator is already dead. The issues are irrelevant. Thank God for Ben Carson.

Substitute Allah and we are back in the Middle

East!

Carson had no shot in the first place. This was nothing more than an exercise in grifting.