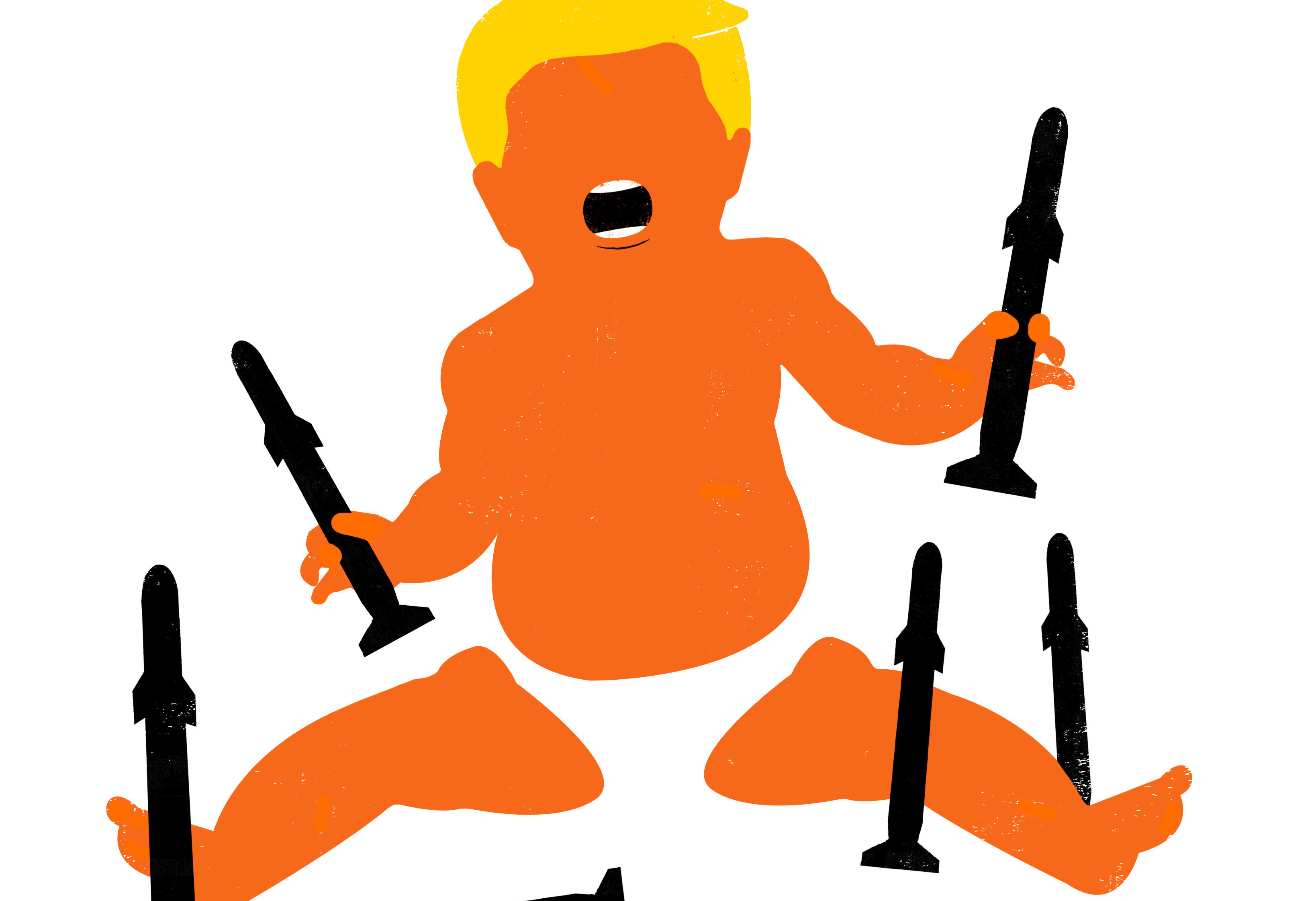

In the emerging American dystopia, reaching for the gun has become the order of the day. From Ferguson and the militarizing of police equipment, through the execution-style killings in Charleston, through the uniformed immigration dragnet bringing fear to 11 million undocumented residents, to serial executions in Arkansas, to Trump’s April speech to the NRA convention, the demons of the American propensity for “violence first” are fully out of the shadows and running rampant in the land. And the Trump administration wants to double down on its real and symbolic commitment to violence in its proposed defense budget.

Unleashing the Demon

The demons of violence were always there. Donald Trump gave them legitimacy through a racist, xenophobic, misogynistic campaign, a willful blind eye to the violent episodes in the country, a “tough guy” rhetoric, and the active encouragement of anti-immigrant strategy.

The theme of the gun is as pronounced in Trump’s foreign policy as it is in his domestic one. However ineptly, since January 20, 2017, the Trump White House has given high priority to the use of military force as the centerpiece of “America First.” A misguided SEALs strike in Yemen turned up little of value and killed civilians and one SEAL. Meanwhile, that lethal conflict drags on with no regional or U.S. strategy to bring it to a merciful end before Yemen descends into chaos and starvation. The much-ballyhooed Tomahawk missile strike in Syria turned out to be a one-off, causing little damage to the field’s operational capabilities. It was all hat and no cowboy, or all “signal” and no message—and there’s no sign of a follow-up strategy to help end that tragic bloodbath.

Then there was the “Wrong Way Corrigan” deployment of the USS Carl Vinson and its battle group to Australia—no, sorry, to the coast off North Korea—whatever. Vinson, who was a real tough guy, is rolling in his grave at this “no show” act of bluster. And the South Koreans aren’t so happy.

Then there was the massive overplay of the use of America’s largest conventional weapon, the Massive Ordnance Air Blast, on a Taliban cave in Afghanistan on April 13. The “Mother of All Bombs,” as the 19,000-pound bomb was dubbed, got tremendous press at the time. Huuuge press! And then, eight days later, a very clever, disguised band of Taliban fighters took down an Afghan Army base, killing more than 100. The Afghan minister of defense and chief of staff resigned, and Defense Secretary Jim Mattis had to scamper over to Kabul to re-wicker U.S. military strategy, once again.

What is this, the Keystone Cops in charge? No, but it is a bullying, militarized, America First approach to national security—a strategy that is badly executed and certain to backfire as other nations grow uneasy about the nature of U.S. global engagement.

Backing Guns With More Guns

America’s one-time friends and allies and other would-be world leaders will grow even more uneasy when they see that the true centerpiece of America First is a massive expansion of the U.S. military. The Trump White House, with budget office Director Mick Mulvaney (once a fan of disciplining the defense budget) leading the charge, is determined to increase the defense budget, not only next year but this year, as well.

The $54 billion increase for defense in 2018 anticipated in Trump’s March “skinny budget” would be roughly 10 percent higher than the military budget provided in the defense budget caps Congress negotiated in 2011. While it would not be an unprecedented increase in percentage terms, it ranks right up there with the one Ronald Reagan pulled off over the head of a reluctant (and regretful) budget director, David Stockman, in 1981. Moreover, it comes on top of an already huge U.S. defense budget—more than double China’s, and bigger than those of the next eight countries combined.

Today, with draconian budget and personnel cuts proposed for diplomacy and foreign assistance, the military may be the only tool of statecraft left.

Military forces cost America a lot of money and they are about to cost a lot more. Trump is determined to make the forces even larger, with encouragement from Republican defense advocates like senators John McCain and Lindsey Graham and Rep. Mac Thornberry, chair of the House Armed Services Committee. Trump’s campaign promises included growing the 275-ship Navy to more than 350 ships and adding 70,000 soldiers and as many as 10,000 Marines to the ground forces.

America already has the world’s most powerful military force. Today, with draconian budget and personnel cuts proposed for diplomacy and foreign assistance, the military may be the only tool of statecraft left. And what a military. The U.S. armed forces are the only global military—able to fly, sail, and deploy ground troops anywhere in the world. Nobody else can do that, because nobody else has global communications, intelligence, bases, logistics, and air and sea lift. Nobody: that’s right, nobody tries, nobody even comes close. Because for decades the United States has assumed it is the steward of the global order.

During the campaign, Trump appeared to abandon this role, saying America First meant America first and foremost. No more nation-building, no more involvement in other people’s wars. That mantra is disappearing rapidly. Despite Trump’s supposed domestic focus, his defense plans would keep the global military capacity of the United States firmly in place and expand it. He has backtracked on his criticism of the Asian and NATO alliances, saying all is forgiven, we are pals. Whether Trump is reverting to “American exceptionalism” and military dominance, and the desire to exercise the global leadership of the past 70 years, or putting America first, if he has his way we will spend more on the military—perhaps as much as $60 billion more per year than defense budgets forecast.

For Trump, more defense dollars and a bigger force are about scaring everyone else into behaving and following America’s needs instead of negotiating. And the goal is to “rebuild the depleted military,” as he told the nation’s governors in February.

Readiness is Not the Issue

This spending surge is almost purely symbolic; in capability terms it is unnecessary. Not only is the U.S. military already a globally dominant force, with technology far in advance of that of other countries, it has no near competitor breathing down its neck.

Despite the gnashing of teeth and rending of garments that are the annual display of military service chiefs pleading for their budgets, America’s military readiness is not on a knife-edge. After more than 15 years of deployment in the Middle East and Afghanistan, the argument goes, the American soldier, sailor, and pilot are tired, worn out, in need of a rest. But the current deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan have not strained the military for over five years, since the Obama administration drew down in both countries. Today, the combined deployment cannot surpass 20,000, the majority of whom are not involved in direct combat of any kind. The “tired force” argument, which might have had merit in 2008, is no longer relevant.

The force that remains is far from a readiness crisis—au contraire. The consequence of nearly 16 years of action is a force that is on point, well trained, well exercised, and experienced at the missions it continues to perform around the world: sailing the world’s seas, flying off carrier flight decks, small-unit counterterrorism operations, and artillery and air support for the ground-force operations of allies in Iraq and Afghanistan. This is not an unready force; it is one at the peak of readiness.

Despite the gnashing of teeth and rending of garments that are the annual display of military service chiefs pleading for their budgets, America’s military readiness is not on a knife-edge.

What military chiefs want is a force trained to face every possible type of military contingency, regardless of how likely it is. The “readiness” measures they decline to discuss are focused on having ground, sea, and air forces that could fight, with no risk, a major conventional war with another peer military competitor—such as Russia or China. That’s the “full spectrum” warfare the chiefs want to be ready to fight, and that’s how they measure readiness.

The likelihood of a ground war between the United States and Russia is pretty remote; the last couple of conventional wars against Russia failed pretty badly for Napoleon’s and Hitler’s armies. And ground combat with China? Not gonna happen. Because both are unlikely, readiness for them is a fiction; a fiction that justifies a larger budget.

The service chiefs know this, so they play accordion games with readiness—expand the concept when it is useful. The Air Force is smaller, so less ready. No, it is smaller because it can be; no other air power is going to challenge the U.S. Air Force. Well, but the Army needs to buy a lot of more-modern vehicles for field operations, so they’re not ready. No, over the last 15 years, the Army bought more modern vehicles than it thought it needed, courtesy of the war budgets. Well, but the Navy is too small, so it is not ready. Ready for what? At 275 ships it’s the only Navy in the world that can conduct global operations. And we really don’t need to be steaming all seven seas all the time; there is no threat that justifies that and we have a lot of naval allies that can help. As for nukes, we have more than enough to provide deterrence and do not need more.

Readiness rants are the hobgoblin of those seeking more funds. They are not the point. If the services needed more money for equipment and training, the easiest source would be their own overhead spending, not taxpayers. In 2010, the Defense Business Board estimated that the “back office” at the Department of Defense—the administration and services, not the combat forces or their support—consumed 42 percent of the defense budget. That office employed 1.5 million civilians and services contractors, more than in the combat force itself. Serious reductions in administrative costs would release far more funds than the services imagine they need for equipment, personnel, and training.

The Defense Department has never felt it had enough money, and probably never will. But it has more than enough forces today to accomplish the missions it is really likely to undertake.

The problem is political, not military. Advocates of more defense dollars, whether in Congress or the Pentagon, are not responding to the needs of national security and military strategy. For those, we have more than enough. The compelling reasons, for them, are bureaucratic and political—more billets and offices in the services, more missions for the planners to make up scenarios for, a prime contractor industrial and technology base to feed, political rewards to deliver at home. These play a role, well understood but rarely discussed, in the demand for more money.

There is a convenient marriage here between the bureaucratic and political impulses and the Trump rationale that more is needed to be scary and dominant. Making America Great (Again?) just seems to go with the mantra of bigger, bolder, better military forces. Not more diplomats; that budget will be cut. Not economic assistance; that’s just a waste of money. This is expensive political symbolism, not military strategy. And by further militarizing U.S. foreign policy—reaching for the gun—it could undercut, not support, American national security.

Gordon Adams is a Distinguished Fellow at the Stimson Center. From 1983 to 1987, he was the senior White House official for national security.

0 Comments