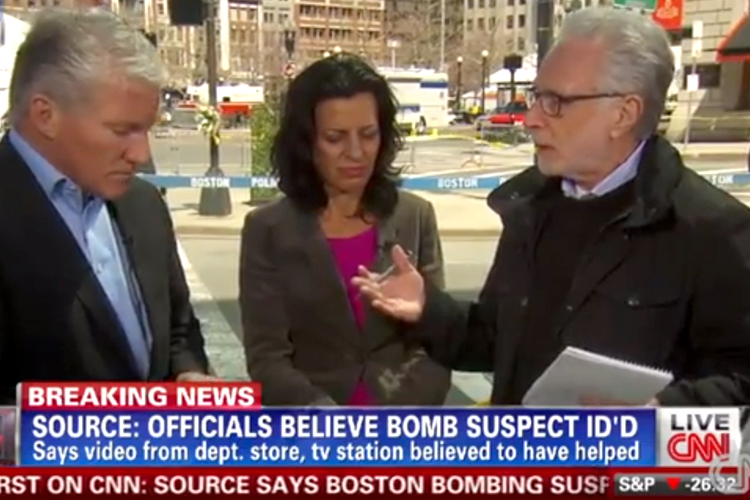

(CNN’s John King reported last week that arrests had been made when none had. AP and Fox News followed suit.)

By Friday night, when we all felt as though we were craning our necks around police cordons to get a better view of the action through our motley screens, it seemed as though the television networks, cable and broadcast, had finally decided to let the story come to them rather than chase leads and tweets the way puppies chase squirrels.

Maybe they were finally tired from all the running around ever since the bombs went off at the Boston Marathon finish line four days earlier. It could also be that even the most jaded of professional bystander with media credentials was overpowered by the prospect of explosive devices along with the uncertainty of their magnitude.

Thinking back to the all-points coverage of the “Night of the White Bronco” almost 20 years ago, the only one who seemed in immediate danger was O.J. Simpson. On Friday, Arpil 19, it could have been much more than one suspected bomber who would die in a hypothetical blast.

But I also think that, after Wednesday’s multi-layered blunder by CNN’s John King in reporting an arrest in the bombing that the FBI didn’t have after all, there was far more circumspection by the broadcast networks with some, it could be argued, close to erring on the side of caution. (The AP and Fox News made the same mistake.)

| The lesson is that it’s not always best to be first. |

As of 8 p.m. Friday, CBS’s homeland-security reporter Bob Orr was still reluctant to say anything about a man hiding in a boat even as my social-networking pages had by then already been chirping about the suspect being cornered in somebody’s backyard in a boat. As I trusted these “friends” of mine generally about as much as I trust CNN (and I mean that in the nicest possible way), I had no problem with Orr’s restraint. In fact, I’m inclined to remember how CBS used to own this profession by exercising such restraint.

One example will suffice because it remains the best-known: The afternoon of November 22, 1963, in a primordial media world where there were only three major television networks – and not too many more stations within reach of the average set. CBS, ABC and NBC were all scrambling for the latest verifiable information after President John Kennedy and Texas Governor John Connally were shot. In those frenzied moments, there were many false leads and red herrings. (Vice-President Lyndon Johnson was seen clutching his chest, leading some to believe briefly that he’d been wounded, too.) In the raw footage of CBS newsroom coverage, you can see people literally screaming in Walter Cronkite’s ear that the president was dead. Yet Cronkite persisted in labeling such reports as unconfirmed or unofficial while ABC, going only with the reported testimony of two Catholic priests leaving Parkland Hospital, went ahead beforehand with a “John F. Kennedy, 1917-1963” logo on its screen. They may, indeed, have been first. But it is Cronkite’s close-to-weeping disclosure of the “apparently official” announcement of Kennedy’s passing that resounds through history as the signature TV image of that moment.

The lesson being, as I’ve told journalism students over the years, is that it’s not always best to be first.

This, of course, was anathema to my newspaper career’s first set of editors who insisted there was no substitute for being first and accurate. I could never figure out, however, which of those two virtues they valued more. They couldn’t both be of equal value, could they? Not my place to wonder back then, though to this day, I still do. The pressure to get stories before the competition was far more prevalent than the obligation to get them right.

| I now believe being in thrall with The Scoop has less to do with informing the public than it does keeping reporters insecure about their jobs. |

Such was the fetishizing of The Scoop in the newsgathering business in those days. You were supposed to collect scoop like ore fragments (or, for those with longer memories, green stamps) and cash them in for the promise of greater professional spoils. I’ve since nudged against the idea that getting scoops was less a matter of serving the reader and more an issue of protecting the company brand. If you weren’t altogether certain you had the whole story or that there were dimensions to the story that needed more time to become visible, then you simply weren’t cut out for this high-stakes business. Almost 40 years later, I now believe being in thrall with the Scoop was less about informing the public than it was to keep reporters insecure about their jobs – and to keep them on the bit, under control and in thrall, really, to their company’s brand.

Still, this was back in the immediate aftermath of Watergate when it seemed as though every 20-something who didn’t want to be in the movies or play rock and roll wanted to be a professional journalist. There were a whole lot of insecure people shoving and elbowing each other prospecting for scoops in the hinterlands. What, one wonders, is the excuse now for cable networks to leap recklessly after scoops in an ever-diminishing landscape of opportunity for pre-internet journalism models? Plenty of amateurs are out there in the Twitter-verse to trip over themselves and misread documents before the pros can get their hands on them. On the other hand, just as many of them will get those things right, too. Where to go? Who to trust?

Some decry this state of affairs. I don’t. In fact, I care so little for who gets it first that I wonder why anyone else would. Reporting anything, especially online or on the air, is a process – and the process doesn’t end even after a story is embedded in print. Rather than making all us bloggers, networkers and busybodies more anxious about our reputations, this brave new world that’s still too new to assume any definable shape should make us more humble, levelheaded and expansive about what we do and how each of us brings our own perceptions to make as complete a picture of our times as our imperfect, imprecise selves are capable. We need to stay serious about our pursuit of truth and beauty – and a lot less solemn about how we go about it.

Making mistakes at the outset may not be the most graceful way of learning such lessons.

But if you learn from them, you recognize that nothing beats the process itself.

Gene Seymour is a Special Correspondent for The Washington Spectator. He spent more than 30 years working for daily newspapers, the last 18 of them with Newsday as a feature writer, jazz columnist and movie critic. He has written for The Nation, Los Angeles Times, Film Comment and American History. Follow him @WashSpec.

0 Comments