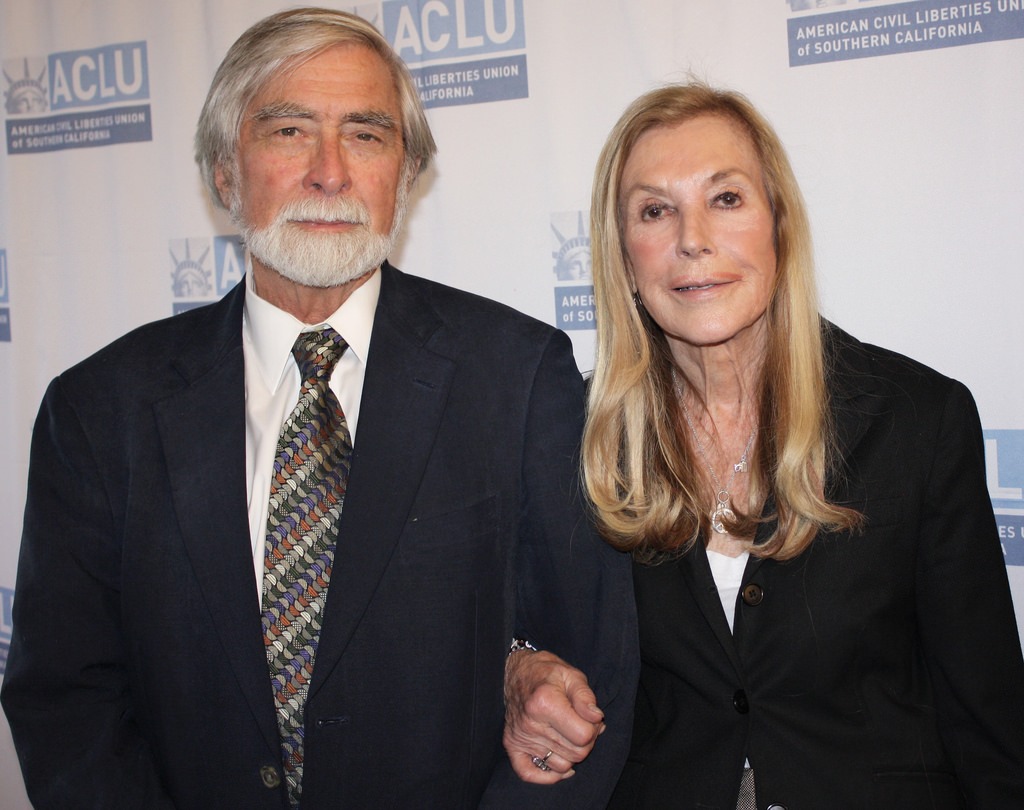

On November 3, one of my cherished mentors, Ramona Ripston, passed away at the age of 91. She had been the executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California for 39 years, between 1972 and 2011. Her husband and soul mate Judge Stephen Reinhardt, who served on the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for almost as long as Ramona ran the ACLU, had passed several months earlier, on March 30, at the age of 87.

Ramona grew up in a working-class family in Queens, N.Y. Her commitment to justice, as well as her keen intellect, prodigious organizing skills, and obsessive work ethic made Ramona a uniquely effective figure not only in Los Angeles but in the national progressive community.

She also had an eye for talent. One of Ramona’s first hires was Mark Rosenbaum, who joined the ACLU of Southern California right out of Harvard Law School and became her legal director and one of the ACLU stars who successfully argued three cases before the U.S. Supreme Court for that organization.

I first met Ramona in 1987 after Stanley Sheinbaum suggested that I become chair of the ACLU Southern California Foundation board. A storied progressive activist and philanthropist, Sheinbaum had occupied that position shortly after Ramona started running the affiliate in the early Seventies. Together they grew it from a staff of six people to the ACLU’s largest, with 60 employees and its own building.

I was dazzled by the scope of the 80-page docket of cases Ramona showed me, which went far beyond the First Amendment work I associated with the enterprise. It included economic and political justice as part of the definition of civil liberties. Traditionalists on the East Coast complained, but the Southern California affiliate was self-funded and had its own policies, some of which deviated from those of the national organization, most notably on the subject of money in politics.

Soon after I was named chair, the affiliate forced the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors to redraw gerrymandered district lines that had systematically stymied the growth of Latino voting power. As a result of the ACLU victory, new boundaries for the first district were drawn, and soon thereafter Gloria Molina was elected the first Latina L.A. County supervisor.

Other successful efforts included litigation that stopped discrimination against Orange County public school teachers with AIDS, a lawsuit to increase welfare payments, and one to boost funding to public schools in poor communities. While still fighting censorship, including mounting a successful defense of the Dead Kennedys on an obscenity charge, Ramona’s lawyers monitored the conditions in prisons, opposed the death penalty, and challenged discriminatory police practices.

In a stroke of organizational genius, Ramona split the affiliate into two entities, both of which she ran. The Foundation was tax exempt and funded the litigation and public education aspects of the ACLU. The Union set policy and was the recipient of the small-donor membership fees that funded lobbying and other non-tax-exempt activity. The Foundation board consisted primarily of big donors, and the Union board was dominated by grassroots activists—including feminists and leaders in the Mexican-American, Asian-American, African-American and gay rights communities.

Ramona was a master coalition builder who forged relationships with street-level activists and labor unions while also motivating wealthy law firms to do pro-bono work on ACLU cases. She recruited Hollywood liberals such as Warren Beatty, Barbra Streisand, Norman Lear, and Jane Fonda; as well as progressive political leaders like Congresswoman Maxine Waters, Connie Rice, Danny Bakewell, and Tom Hayden; liberal Democrats such as Senators Alan Cranston and Barbara Boxer, and L.A. Mayor Tom Bradley—all of whom became regulars at ACLU events. She mentored subsequent L.A. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, who later became the Union president, an affiliation he proudly advertised in his campaigns. Ramona once even got Republican Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger to contribute $10,000 to the ACLU.

Ramona was the first woman to run a major ACLU affiliate and was allied with feminist leaders such as Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, and Peg Yorkin. Many of the leadership positions at the organization were held by women. However, Ramona was immune to political correctness. At one point I obtained a contribution of $25,000 in connection with a broadcast by the rapper Luke Skywalker, who had been arrested for obscenity in Florida. Though some feminists protested because of the singer’s misogynistic lyrics, Ramona insisted on taking the money.

In 1988, when George H.W. Bush attacked his Democratic opponent, Michael Dukakis, for being a “card-carrying member of the ACLU,” the Southern California affiliate produced some TV spots while the national organization was reluctant to do so. We shot one with Burt Lancaster, who had been chair of the ACLU in the 1960s, prior to Sheinbaum. Lancaster turned to Ramona at one point during production and said, “Honey, could you get me a cup of coffee?” Several of the younger women on the ACLU staff gasped in horror, but Ramona cheerfully got the aging film star his beverage. “These old guys don’t know any better,” she said with a laugh.

During my seven years as chair, the most memorable issue that Ramona dealt with was the successful campaign she spearheaded to get rid of L.A. Police Department Chief Daryl Gates. Gates was famous, among other things, for the notoriously racist statement that African-Americans had died of LAPD choke holds because the arteries in their necks were different from those of Caucasians, and for opposing police reform in the wake of the beating of Rodney King. Ramona generated public pressure for the removal of Gates, and Sheinbaum was named by Mayor Bradley to become president of the Police Commission that subsequently led the effort to force Gates from office. Afterward, Ramona maintained a dialogue with successive LAPD chiefs, and the improvement in the department over the years has been widely recognized.

Until her retirement in 2011, Ramona continued to work 12-hour days and kept the ACLU of Southern California on the cutting edge of every issue. Yet she often privately worried that she had not made much of a difference. That is one thing she was wrong about.

Danny Goldberg is a longtime music business executive who began his career as a journalist. Since 2007, Goldberg has been president of Gold Village Entertainment. He is the author of In Search of the Lost Chord: 1967 and the Hippie Idea, Bumping Into Geniuses: My Life Inside the Rock and Roll Business, and Dispatches From the Culture Wars: How the Left Lost Teen Spirit.

0 Comments